I had come to Harare on the train from Bulawayo that was taking first year students to university for their orientation week. I remember my mum, dad, my three sisters at the train station, those last moments, my head out the train window, saying our teary goodbyes and then the whistle…and I was off…to my new life…a university student…the first in my family. The train was filled with us first years, trepidation, hope, excitement, a tangled web of emotions bristled up and down the full carriages. What awaited us there, in this new world, free from family, our own individual selves, boys and girls let loose.

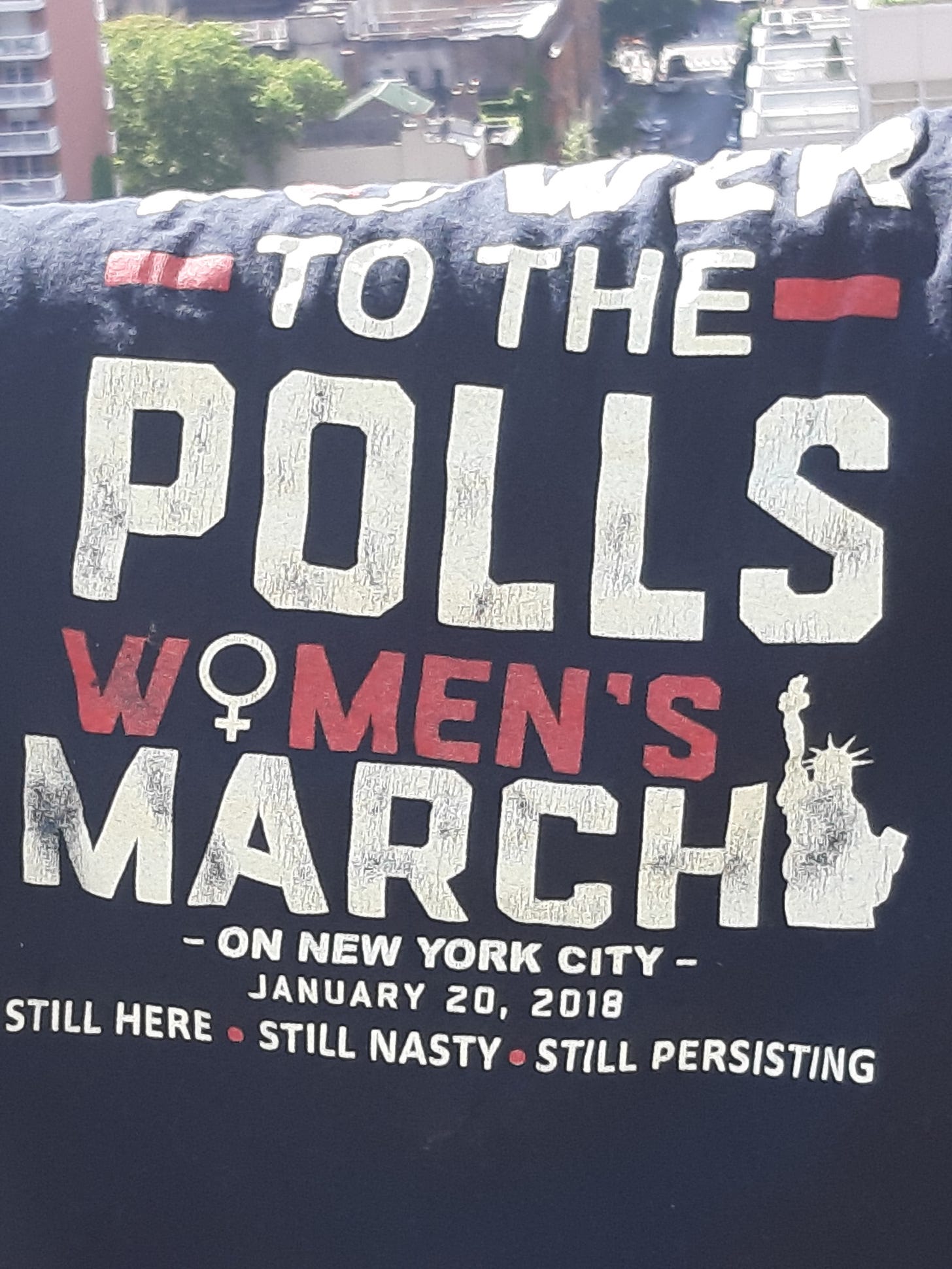

I was lucky that I found myself a group of friends from Bulawayo. We would meet in each others’ tiny rooms, prepping for a night of clubbing. We had two hangouts. Job’s Nightspot downtown which was full of low-level criminality but good music, and Playboy Nitespot in the city centre whose name pretty much sums it up, but we went there because the bands we knew played there and often we got free entry. We would go there crammed in emergency taxis wearing short skirts and what in Zimbabwe is considered revealing, ‘whorish’ dresses…too much leg, too much arm, too much midriff, too much cleavage - I am surprised now at our audacity, our courage, our feminism… we would not be intimidated. We had every right to wear what we wanted. But, we were not blind to the risks.

Girls on campus had been surrounded by mobs of male students and ‘relieved’ of their short skirts. At a fashion show in the student hall I had watch a group of male students lunge their way onto the runaway and assault the models. Wearing trousers too was seen as a provocation -so you want to be a man heh? Female students could not access the library after sundown because of the possibility of getting accosted by male students on the dimly-lit paths from the Hall of Residence to the library. The Student Union Bar in the evenings (and often during the day) was a no-go-area for female students. Attending any function, even a movie screening or a cultural event in a lecture hall, could leave you suddenly feeling vulnerable as you realised that you were one of very few female students there; this sudden awareness of the air changing - I tried to capture the pulse of such a moment in my third novel, An Act of Defiance:

She is seized with the one thing, the horror of it: something bad is happening as the voices grow louder, closer and then a silence that tells her they are there, right there, upon them.

It did not help that alcohol at the Student Union bar was heavily subsidized by the government. The male students drank to wild excess. Every once in a while a friend and I would take a stand and have a beer straight from the bottle seated at one of the tables at the Student Union. We were defiant in the face of jeers, taunts and slurs - we never stayed long, and there was never any other female students to join us, to commandeer the tables and claim the space as ours too.

Two incidents that happened to me shook me and led me to leaving my student residence for my personal safety.

A group of us, led by a third-year student, started a magazine: Woman. It was the first magazine on campus, I think, but certainly the first one dealing with women’s issues. The third-year student was the editor; I, the deputy. There was on campus a certain student who went by the fitting moniker Chief Hooligan - he ruled the Student Union in a campaign of terror and he was widely feared. In our first (and what turned out to be, our only) edition the editor of our magazine wrote an anonymously penned mocking, skewering article about him using only his moniker. Reaction and retaliation was swift. I was coming from the bathroom, a towel wrapped around me when a meter from my room I saw that the door was open and standing there was Chief Hooligan. It was too late to turn, make a run for it. I remember fear like a dense shadow fall on me but also a calmness. Chief hooligan had the magazine in his hand and, seeing me, he slurred, who wrote this shit? I shook my head. I, I don’t know, I said. He was no fool. He knew I was lying. He was incredibly menacing. I have no idea how I remained so calm, He asked me again, his breath stale on me. I’m not playing, he said. Who wrote it? Again I said, I don’t know. He slapped me then. A hard slap that knocked me back. And then suddenly he just seemed to get bored. Or he needed another drink. Or he thought he’d made his point. He dropped the magazine, turned and left. My cubicle was soon a spectacle - female students peering in to see the damage Chief Hooligan had done. Later that day, I met up with the editor. Chief Hooligan had come to her first and she had denied that she had written the article. She had sent him to me. She apologised. That was the end of our magazine. The fear was too strong. Intimidation had worked, served its purpose.

In the second incident I was in the room of a male friend of mine, a medical student. One minute we were chatting away about this, that and the other, and the next he got up, so casually, went to the door and locked it. It was so shocking how suddenly menace filled the room and the danger I suddenly found myself in was so unexpected, from where it came - him, this man, this friend who I trusted. What are you doing, I tried to sound light hearted, come on, open the door, I have to go. He too, made to sound that this was all in good fun, nothing sinister or out of place, we’re just having fun, he kept saying, we’re going to have fun. I didn’t want to make him angry, to see what he would do if I made him angry. Please, I said, open the door. I was trying to keep the fear out of my voice, but it was there, and I could see that it gave him a kind of satisfaction to have me afraid, of him, his power. If he touched me I knew that there would be nothing I could do to stop him. He was taller, stronger, he had muscles from the gym. I might try to scream and he would push his hand against my mouth and stop me. Even if I screamed I was in the male hall of residence. Who would even heed my cries? Come on, open the door. I was near tears, the dawning realisation that that thing that happens to women was truly going to happen to me. And I would submit to it, because I wanted to live. I feared too that this student, this friend, would suddenly turn violent, I saw it then in him the possibility of him balling his hand into a fist and punching me. And what if he then opened his room to any student who wanted some ‘fun’. I pleaded with him now, no pretense. Please open the door. And then again, as if boredom set in, or he had exercised enough of his power, was satisfied with its effect on me, or had simply changed his mind about taking what he wanted, he turned and unlocked the door as casually as he had locked it. I remember his smirk as I walked out.

An Act of Defiance revolves around a rape and its aftermath. It is about trauma and it would be so easy to twin this with ‘recovery’ but what does that mean? How does one ‘recover’ from rape? The novel follows Gabrielle as she navigates her life - lawyer, mother, lover, rape survivor. Her life does not end with the rape - it is defined and redefined by it. I am startled as I write this now to see that Gabrielle’s story is the other story of Irene if that male student had kept the door locked and raped me. It is that other life. What I think it might have looked like. Fiction is autobiography.

Rape is always there, an ever persistent worry that limits, a weapon used in times of peace and war, a torture of the mind and the body. It is there when I walk in the underground parking of our apartment building and I hear the click click of my heels on the concrete; there when I wait for the elevator to come down, alone. It is there in split second decisions - should I go there or not; should I stay a bit longer or not; should I brush past this stranger’s gaze or not…

In Peace and Conflict, the rape that occurs is unspoken: Robert, the ten-year-old narrator understands that something very bad has happened to Aunty Delphia, something perpetrated by government forces; it is something he knows that has filled his previously carefree aunt with sadness and fear.

I think now of reading Doris Lessing’s autobiography of her life as a young woman in Rhodesia and England. I remember stopping at a line of hers where she talks about the nocturnal walks she would take in Salisbury and later London, well into the early mornings, going into alleyways, wherever her legs would take her, without fear. I read it over and over. Without fear. Without nervousness. As if she was a man. How liberating that must have been, that must be.

There were other passages where she had little patience with the young girls of her then present (1990s) - how easily it seemed to her they were intimidated, shocked, prudish.

And I remember then, and rereading the passages now, the feeling of deep unease as it felt that the passages veered into victim blaming territory - something has not happened to me and so, if it happens to you… as if it were solely mind over matter. By the dunes in Ostia, the seaside town near Rome, I had had my bottom casually pinched by a passing man, in Rome I had had those kind of looks - did I not have enough mettle, an inner core of steel to just take these invasions as mere nuisances and not as assaults on me?

If a man were to get assaulted while walking an alleyway at night he most likely be just taken as a victim of a crime- no questions about his right to be in that alleyway at that time - were it be a woman the accused becomes her - what were you doing there then? This is what happens to girls who do things like that, inviting trouble.

In my first year at university I had on one of my walls images from a magazine feature on what really happens when a woman has an abortion. The accompanying article did not say ‘abortion’ but ‘kills a child in her womb’. I cannot remember what magazine I got them from, what christian magazine of the time I could possibly have found them in, and where, or was it one of the South African woman’s magazine that I would dig up at the Book Exchange in Bulawayo? But the images were up on my freshman wall, just over my bed. One day Kerry, my American exchange student friend, came to my room and saw the pictures, stage by stage images of what must have been a late term abortion. Kerry said, you’re against abortion. I was surprised she could even ask that. Every good person was against abortion. I had an abortion, she said. She didn’t say anything after that. It was just a statement. She didn’t argue with me about my abortion stance. We talked about something else and then she left the room. I took down the pictures. Kerry was a good person and she had had an abortion, and the images up there mortified me and, in a way I could not understand then, shamed me. I knew that the pictures had made Kerry sad; it was in her face and in her voice; bubbly Kerry had seen the carnage on the walls and I had inflicted pain on her, what kind of person puts images of babies dying, that is what I believed then, on their walls? Why put them there except to admonish anyone who came into my room with perhaps other ideas; why put them there but to declare ones own ‘purity’.

Growing up, I had overhead conversation between my mother and her friends about someone putting a needle up there to get rid of an unwanted pregnancy. I had heard about too much blood, and death. In The Boy Next Door, school girl Lindiwe accompanies her best friend, Bridgette, to a house in downtown Bulawayo to get an abortion. Lindiwe waits in the dingy room as the woman does a backstreet abortion. In Zimbabwe, The Termination of Pregnancy Act, which was first enacted by Rhodesia’s white minority government in 1977 and kept in place by the government of independent Zimbabwe in 1980, allows for abortion under certain circumstances: risk to mother’s life, risk that the child will be born with serious physical and health defects or if fetus was conceived as a result of rape, incest or intercourse with a mentally handicapped person. Statutory rape is not a legal ground for abortion. Illegal abortions have a statutory five year prison sentence. Bridgette’s unwanted pregnancy at the age of sixteen is not grounds for an abortion in Zimbabwe. Growing up, there were stories, almost every day it seemed, in The Chronicle, Bulawayo’s paper, and The Herald, Harare’s paper, about baby dumping; babies found inside toilet bowls or drains, dead. Girls would hide their pregnancies and have the baby alone and ‘dump’ them. In an Act of Defiance, Danika Dube is the victim of a statutory rape (a pregnancy resulting from it) and much of the novel is about the quest for justice for her by the young lawyer, Gabrielle Langa.