Incidental Requiem

the jazz musician from Finchley Central, reborn

I began a novel, years and years ago, lost now I’m sure, but it was called The Jazz Pianist, and it was in the form of a soliloquy–

I have found it! In the depths of years and years of files - Incidental Requiem - a flood of emotion as I read those first lines-

He is dead now.

He had begun to smell when they found him.

When he was young he played the piano.

He was young when I was with him.

and how much we forget, Fabio on reading Incidental Requiem made the casual remark about how I had captured that old man in Finchley Central and I was completely surprised that he was the inspiration… the story had not come from nowhere, after all, and how could I not have realized/remembered that I was imagining a version of Peter’s life, not in London, but in a far away land, America. And I had done such a good job of capturing ‘him’ that Fabio, almost fifteen years later, immediately saw him in my imaginings.

Writing this now I suddenly become conscious of two other sources of inspiration for the story, long buried in my subconscious, even when I was writing it.

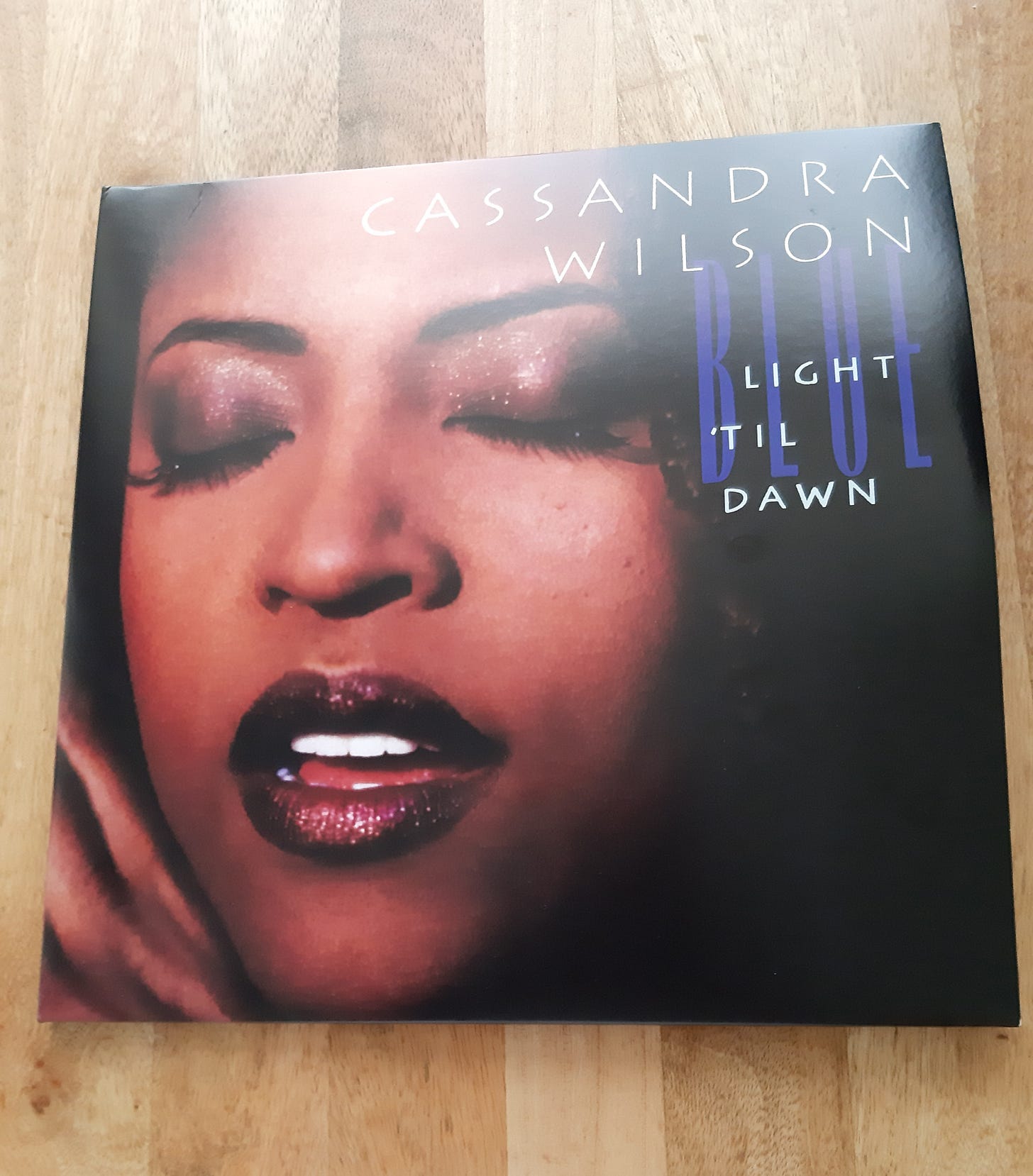

An evening with Fabio at the legendary Blue Note Jazz Club in Greenwich Village in the early 1990s where, sitting by the bar in a packed, smoke-filled room, we listened to a real jazz singer, Cassandra Wilson - for me that moment was electric; I could not believe that I was in New York, in this place - it was as if I was in a movie, cries of ‘yeah’ , ‘that’s right’, erupting from the audience as that soulful voice held us captive.

I recently went back to The Blue Note, after twenty nine years. The waitress asked if we had been there before, and exclaimed, that was before I was born, when I told her, and the passage of time was also felt in the room no longer shrouded in smoke, indoor smoking in bars and restaurants having been banned in New York in 2003. On stage that night was the grammy-award winning, New Orlean’s born, Nicholas Payton working his magic on trumpet and piano, with his band. I was struck by a line on a voice-over during one piece …the notes are my paint… and this made me think of Van Gogh’s word paintings when he would write to his brother Theo detailed, evocative descriptions of the paintings he was working on…

and how art in its various forms is about opening the world, the heart, and this is what I was trying to do with Incidental Requiem, even though I did not quite have the language of, for music, just the feeling of what I wanted the story to convey, loss, the rhythm, tone and texture of it.

That evening at The Blue Note I rediscovered my love for jazz: I was once again moved by the sublime clarity of the piano, the trumpet, the double bass and drum set, how each note could be isolated, how it was held in the air, and how I felt it in me as a gurgle of joy, how the audience responded to it in bursts of acclamations. This was music. This was jazz.

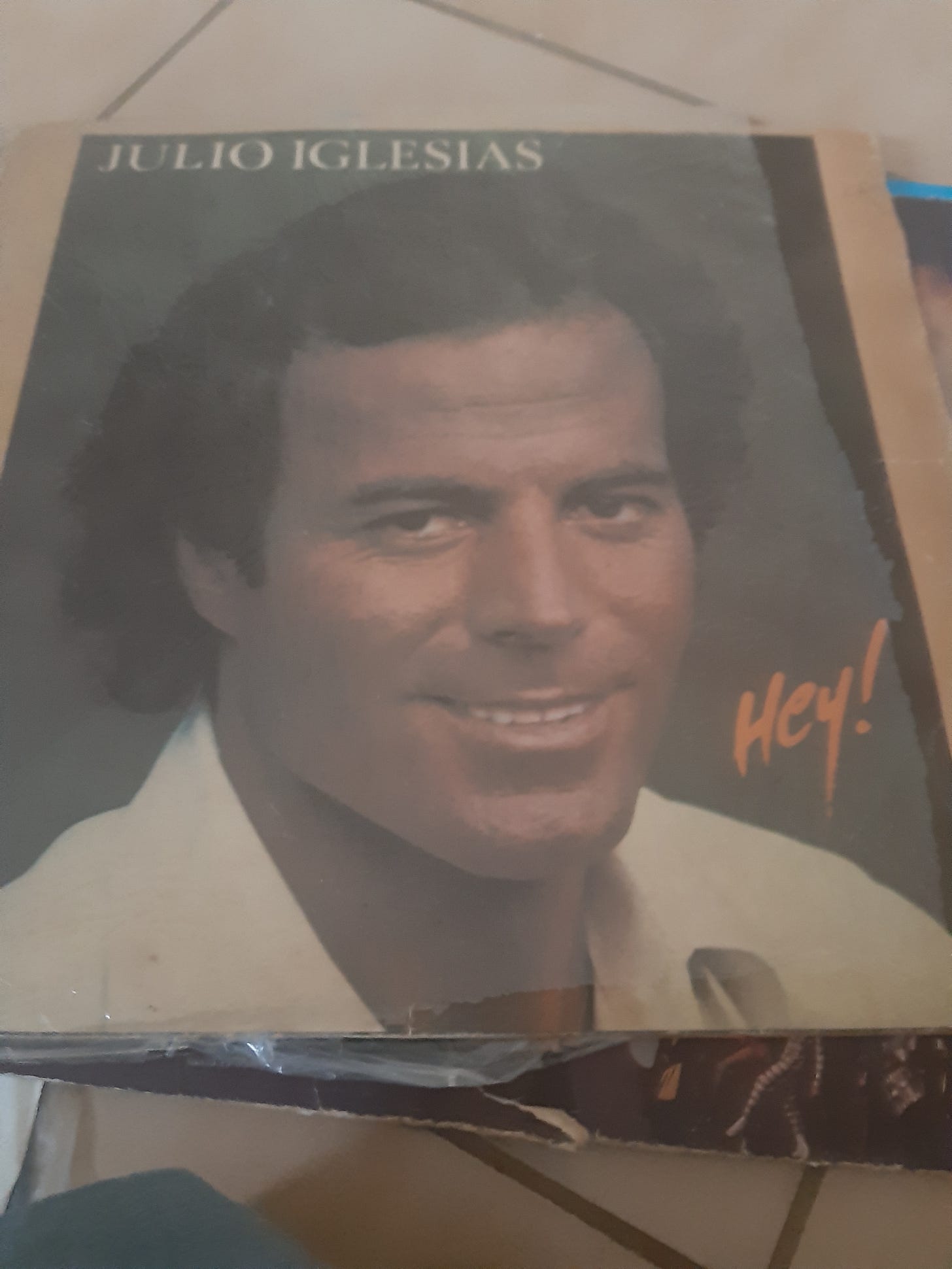

I have now a longing, a deep yearning for Fabio’s old cassette tapes (originals and mix tapes) slotted in the little pine shelf he made and fixed on the wall just above his bed so that they were way easy to reach - the classics, Louis Armstrong, Elle Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, Dizzy Gillipisie, John Coltrane - my introduction to this music; till then my tastes were firmly centered on pop - Spandau Ballet, The Pet Shop Boys, Madonna (scandalously singing and dancing to Like a Virgin along the verandah of my childhood home, the walkman hooked over my waistband while keeping a nervous eye out for my mother or father), Wham, Michael Jackson and, inexplicably, Julio Iglesias - my first loves.

Those long, lazy Saturday or Sunday afternoons come back to me when Fabio would put a tape in the cassette player and the two of us, lying on the bed in his room in Rusape or in the room in the cottage I rented in Harare, the sun filtering through the curtains, the trumpet, sax, horn, piano, bass, enveloping our bodies, filling the room. Unlike pop, it was music that did not call out to me to dance but which moved my spirit, something deep in me, unlike the classical recording that were part of Fabio’s collection too - listening to it I suddenly felt no longer a child, but someone grown, and knowing. So, perhaps then, the genesis of Incidental Requiem, is much older that I thought, going all the way back to the late 1980s when I heard those first chords.

Another memory now, the wonder and thrill of discovering, when I was writing The Boy Next Door, that old Satchmo himself, the Louis Armstrong had come to Bulawayo in 1960 and played to a rapturous audience of black Rhodesians at the Queen’s Sports Grounds, home of rugby.

And then there was the trip to New Orleans, the birthplace of jazz and the blues, on my own to attend an education conference. It was in the mid 1990s and I had not known it when I landed that New Orleans was then considered the most dangerous place in America, but I soon felt the pulse of it when I got in the taxi and gave my driver the address of my hotel. Are you sure, he asked. Yes. It was, he said as he drove, on the boundaries of a bad neighborhood, lying as it was just at the edges of the Garden District. It was not a safe place, and in the coming days, whenever I told a taxi driver they would all pause, wondering if they should accept me. I had chosen the hotel from The Lonely Planet Guide book which had talked about its charming, unique flavor, a historic mansion. It turned out to be more of a boarding house, and my room was a simple, basic one. I felt so claustrophobic in it that I soon went out, taking the legendary St. Charles Street car into the famous French Quarter. In the street I stopped a woman in the midst of the commuter rush home to ask where Bourbon Street was; she gave me directions with that warning again, Be careful. I was a ball of nerves by the time I found the street; it looked eerily abandoned - I found a bar where I had my first meal - a loaf of bread, carved out and filled with shrimp gumbo. I hardly knew what to do with it. I struggled to find a taxi home, and when I did it dropped me at the edge of a street. I had forgotten to take the address of the house with me, and all the houses looked the same. I went up the stairs and put my keys into the door before me… the lock would not budge. I tried over and over. No luck. I waked up and down the street trying to will memory, recognition but I was lost. It was night. Cars passed slowly by, one or two rolled down their windows, called something out to me, gesticulating to me to come over. I walked round the block in a panic, my heart pounding. There was nothing, nothing. What was I going to do? This was the days before mobile phones. My first night in New Orleans might very well be my last. One of those cars, beaten-down trucks would stop and - then I saw a light in a room. I yelled until someone heard me. They opened the front door. It was a man. I told him my story, barely coherent, fighting the flood of tears threatening to engulf me. And, in one of those wildly, fortuitous moments it turned out that he was a caretaker of one of the buildings of the ‘hotel’ and he led me to my room, recognizing the key. Now, I think of this sometimes, how fate, destiny can turn on a dime. What if, that man had not been my kind savior but someone intent on doing me great harm, who would have led me to his lair, me following meekly to my grisly fate. I have just checked the murder rates for New Orleans the year that I went there: over four hundred murders, the highest recorded number in the city’s history.

Fiction is autobiography reinvented - it is the what if?

The conference centre was on the Mississippi River and I realize now that some of the atmosphere of Incidental Requiem comes from there, the memory of the walks I would take along the riverfront during conference breaks, the tugboats and ships on that might expanse of muddy water, its mythology and place in America’s violent story. There were also the walks I took, up and down the streets in that of many ways the most unAmerican of American cities, with its soul-stirring music and voodoo and creole. The sight and sound of the old-time street musicians imprinted themselves on me, playing their banjos, harmonicas and singing the delta blues.

I am not a musical person at all. I cannot hold a note. I do not play any instruments. So I am struck by how I attempted to give Incidental Requiem a kind of rhythm and flow, a stab, I suppose, at some kind of musicality.

To grow as a writer you have to be brave. Courage! To try new things, to experiment with form, style, language. This may lead to failure, the striving for but not quite getting to the essence of the thing, but it may also reveal a surprise or more than one, it might simply be a turn of phrase that gives you pause, words upon words and one might extract a nugget to use, elsewhere. Nothing is ever truly lost.

Coda: Extract from Incidental Requiem (2001, unpublished)

He is dead now.

He had begun to smell when they found him.

When he was young he played the piano.

He was young when I was with him.

"Always young!" he promised. "Eternally young!" he declared in defiance to ...?

He would say, "Old, twisted hands on these keys are obscene."

You look down at your hands. They lie flat against the wood; long, thin tapered fingers resting there, and then, as though it hurts for you to look any longer or are you afraid at what you see when you look so hard, you angrily snatch them away. Did you know, even then?

"It's like a lecherous old man having his way with a young girl, you would say. When I am forty I will have them hacked off."

Forty, you thought it would be too old for you, for your hands.

I remember him then. He was beautiful. The careless, inspired tenderness of his hands as they charmed and caressed the keys, as they had their way with the shy, willing ivory. I would say, you play as though you were making love, you and the piano. He would laugh. I would be naked under him and he, he would lightly dance his fingers over me and say, let me play you then the way I play the piano.

He played in the cool heady bars that ran frantically along the northern end of that long crazy river. He would look into the water and say, there is music in this river, way down under, it's hidden there for my hands to find.

The only white man who can play jazz the way it's meant to be played. It was how they introduced him. It was what they put in the posters. The only white man who can play jazz. It was who he was, who he became.

You were tall and angry.

You were at your tallest, your angriest when you were seducing the piano. You would say, she likes a strong hand and I would look up and say, there is another who likes one too.

When the man phoned and told me that you were dead the first thing I asked him was,"Why me?"

He did not understand. I had to ask him again.

Why me?

Why tell me?

He said,

you are his wife.

You would play in the bars. Remember those bars? How they leant one against the other, creeping up to one another like bad thieves, stealing secrets from each other, you'd say. I would watch you. I would watch the women too, the ones who came alone. You knew that they watched you, that they wanted you and, before we became lovers, you would say, I pick one and fuck her with the piano. You would say such things.

I did not come to your funeral.

They said you had begun to smell. Is that true? They found you in a cubicle surrounded by beer bottles. You were scrunched up in your bed. The T.V. was on. You had choked in your own vomit.

I did not come to your funeral because you died that way.

I cannot forgive you.

Remember when I left you. Remember then. You were spread out on the bed playing with the hairs on your groin. I was the insipid Evening Feature you had chanced upon. You had a show at eleven and in between I would entertain you. Mildly.

I said, you have slept with one bitch too many. I can't stand it anymore.

I cried. Predictable.

I must have looked at you, wildly. I must have, begged you. I must have stood there, naked, afraid. I must have put my clothes on. You must have watched. I must have opened the door and left. My legs must have carried me to some other place. They must have done that.

When did you start drinking beer?

When did you start living in cubicles?

When did you start choking on your own vomit?

When did you start living on your own?

When I knew you, you drank scotch, neat. You said the piano liked the smell of it. You said it was in the way the smell of the scotch circled the keys. You had a way of saying what should have been just talk, just silly talk which should have meant nothing, that made it sound like some significant, true thing that had to be stored, remembered. Something that in the end would have to be told.

You would drink the scotch as though you were smoking, just for pleasure.

I remember: your hand circles the glass; the glass disappears in your hand; you lean your head back, a smooth, gentle, flowing leaning back; you give a whisper of a smile (to whom?); one long drag and the scotch disappears; your eyes are closed and then you exhale and, like smoke, the scotch circles the keys. You run your fingers through the keys (this is how I want you to touch me), tentatively, with the shy sure expectation of pleasure to be taken and given. You begin to play. We watch you, our eyes refuse to leave you. Do you do it all because we are there, watching? Are you amused? Do you laugh at us? Are we ridiculous? Am I? We are suspended in your will. Do you relish your power?

I would pour the scotch in the glass. I would bring it to you. My fingers, your fingers possessing the glass, the closest way we had of touching I can remember.

You lived, you lived... where? Where did you live?

You lived everywhere. You belonged to each space. You were what gave life its form, its right to be.

You would say, come here. I would stand against the door, my fingers trembling as they undid the buttons of my blouse. You would say, come here. You stroke my face. You stroke it out of, out of.... out of pity and perhaps shame. My shame. You cup my chin and you say, will you do everything as I say, everything as I wish it to be. I nod. You say, I'm not sure you will. I'm not sure at all. You drop my chin and you, you leave me in my shame.

You are dead. You are under the ground in a cheap wooden box. Do you like your new home? Does it welcome you?

You said, it hurts to have all these homes. It hurts not to choose, to have too much freedom. One has to be tied down.

You loved the piano. You loved it because it tied you down. It said, this is home. This is all there is.

You died,

seeped in your vomit.

You are less than what I had imagined.

Less than what I wanted you to be.

I left you.You watched me leave. Perhaps you even applauded the way I did it. I heard that on that night you played a new piece. You called it, Release.

We are in your room. It is bare of everything except the large piano in the middle. We make love on the floor.

I must think of you as dead.

I must think of you as the ugliness of death.

I must think vomit, cubicle, beer.

You were a star. They loved you. The white man who can play jazz. They said that you made people want to fuck when they heard you. It's true. I always felt that way. And I could smell the sex as your hands played with all of us.

We became, man and wife.

Man and wife.

Subject and object.

It is as exactly as what the bored man said.

You are the man and I, the wife.

We are thus joined.

We could have turned it into a joke but you were serious and I panicked.

We married

I, pregnant.

You, you.... what?

You said, well then, we'll have to get married.

We'll have to get married.

What did that mean,

exactly?

I smiled. Yes, I did. I smiled. You would be mine. Completely.

…..

They have made the story of your life.

They have a handsome, weary stranger as you,

a beautiful, off-key stranger who is me.

You are a brooding, tragic, romantic figure.

They have cut out what they say are the more sordid bits of your life.

in-between the cracks I see you,

in-between the cracks,

I find you.

They have used my book.

They have named it after my book.

These Hands of Mine: the story of a jazz player.

Do you mind?