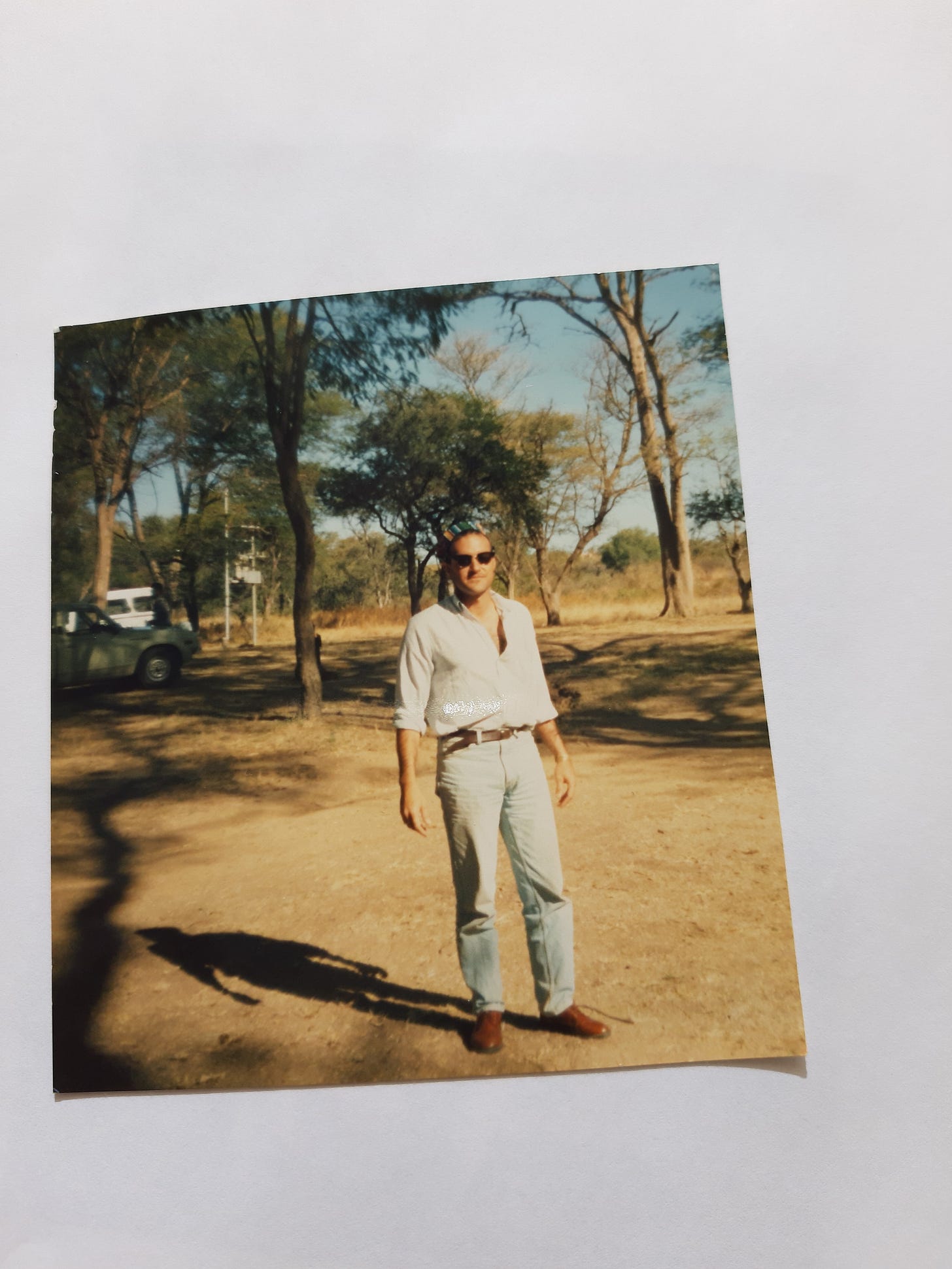

I was a twenty-two year old University of Zimbabwe student when I met a dashing twenty-nine year old Italian NGO worker, in this, his first posting abroad.

He was one of the ‘expats’ who had flooded the newly-independent country, employed as a ‘technical expert’ by an Italian NGO that was building markets in the rural areas of north-eastern Zimbabwe.

It is true to say that Giorgio in my novel, An Act of Defiance, is inspired by Fabio; that he has his soul.

We were married, three years later, on a cold, windswept day in the tiny village of Bernisdale in the Isle of Skye, the Scottish highlands and a loch making for a magnificent backdrop.

I had discovered Scotland as a postgrad student in London- standing squashed in a stuffy, crowded underground train I had glimpsed, in the sweaty, stifling crush of bodies, an advert - after a holiday in London you need a real holiday - something to that effect - accompanied by a breathtakingly peaceful picture of a sweep of mountains and water - the Scottish Tourist Board was right and genius in their marketing. I did want to be out of here to there. Weeks later, I was indeed there among the mountains, the lochs (and their monsters), the glens, the castles; traversing the country by train (and what colorful characters I met on that trip, weather-beaten oil workers on leave from platforms on the North Sea to fortune tellers with their second sights and crystals), backpacking and staying in youth hostels, my favorite the one on the foothills of Ben Nevis. I took the ferry to Skye (long before the bridge was built linking it to the mainland) and I fell in love with it. The Scottish people I met were always welcoming and the nature was glorious. This was where I imagined myself as a bride.

Fabio flew in from Bogotá, and as soon as my final exams were done, we set off by car to Scotland, to get married.

He wore a pair of jeans and a blue shirt; a tie and a jacket spiffed up his look. My wedding attire was a minidress splattered with red roses, black platform shoes from a shop near Covent Garden in London, a purple chiffon scarf which the wind kept whipping round my face and pre-colombian style earrings from a boutique in Bogotá. In my hands, a posy of white and yellow daisies. My afro was pushed back and tied with a black-and-white silk scarf; I found that this was the best way to style my hair without perming or straightening it. I had black stockings on but, getting out of our hired car and leaning against Fabio, my stockings caught the velcro of his windbreaker and ripped. Not a good start to the ceremony.

I hopped back in the car again and took them off, upset with Fabio for ruining my look, but I could not remain annoyed for long: I was getting married!

We ran across the street to the cottage that was the temporary registry office because the real one in Portree had burnt down. The registrar was very young, very fresh-faced; she had just passed her registrar exam, and this was only her second wedding officiating. Where were our witnesses? She asked us. Fabio and I looked at her. Witnesses? Yes, we needed two of them. Of all the paper work we had done, documents flying between Bogotá, Harare, Bulawayo, Rome, Portree, how had we missed this fundamental requirement - witnesses? Fabio and I looked around the room as though the witnesses would magically appear. And then we looked at the young registrar as if she might find a solution. We had to find witnesses, so out we went searching for them.

Next door, there were two women working in their garden. It turned out to be a mother and daughter. ‘We’re getting married,’ I pleaded. ‘Can you please be our witnesses?’ They had hardly time to wash their hands of the earth they had been digging into. No time to change. They were fine, fine as they were in their gardening clothes, we reassured them. And so, they witnessed our marriage, our vows. They turned out to be a lovely pair, perfect witnesses, who treated us to cake and tea in their cottage after the ceremony and who chatted lively about the exciting turn of events to their day. As I was leaving, the mother hung a string of bells around my neck, and I skipped merrily back to our car, the ringing of the tiny bells my belated bridal chorus.

We had eloped.

Three days before, we had squeezed into a red phone booth in Hampstead and phoned our respective families. ‘We’re getting married,’ we said giddily, me to my mum in Bulawayo, Fabio to his in Rome. The news was relayed to our fathers. Everyone was in shock. His father had to sit down to take it in. Mine was deeply offended that Fabio had not asked for his blessing. But they came round and accepted that this was the way we did things - our own way, in our own little, irreverent bubble.

We left for a week’s honeymoon, driving around the isle. We arrived, the first evening of our married life, at our hotel on the foothills of the Cullin mountains; the manager greeted us with an extravagant bouquet of flowers and a bottle of champagne - both from friends in Bogotá. I was struck by the wording on the card….To Mr and Mrs Fabio Sabatini. I had been subsumed, but I was so happy. In the morning, we were surprised by the sight of a bottle of champagne on the bonnet of the car - a fellow hotel guest, it turned out, had seen the two boxes of wedding rings and the bouquet of daisies lying on the dashboard, and had treated us.

Our wedding rings, we had bought two days before, simple gold bands from H Samuel in London, twenty-five pounds each. My engagement ring is a more recent acquisition. I picked it out from a casement of rings in an Antiques Emporium in Plymouth. It is 1930s art deco, flower shaped with a very slim band, a beautiful, delicate piece. I fell in love with it instantly; it glided easily on my finger as though it had been waiting for it all these years. And then Fabio said, ‘That’s your engagement ring,” and I loved it even more. He officially put it on my finger over dinner in a French bristo, on my fifty-third birthday, R looking on, a big grin lighting up his face; his parents doing things their way.

Being in a mixed-race relationship, in different parts of the world, has been fraught with challenges, people’s perceptions of who we are and why we are together and why we should not be together.

Zimbabwe 1980s, when we met: in those days, there was the perception of girls going after foreigners because they had money and that foreigners were having their exotic flings. In certain eyes I was a sell out, a slut, a whore. He was a sugar daddy, a colonizer. Fabio was, for the most part, the hapless murungu who could be conned by either a sob story or his white guilt. In my case, misogyny made everything worse and a new word I have learnt in America - this mix of misogyny and race- misogynoir , the unique discrimination that black women face. I felt this everywhere we went.

In Havana, in the early nineties, the hotel porter, in the very small elevator taking us up to our room turned to Fabio and remarked casually, ‘You have to pay for her.’’ He mistook me for a Cuban girl, and a Cuban girl could only be in the elevator, going up to a hotel room with a tourist if she was a prostitute. So began an uncomfortable and distressing week. It was fine when Fabio was at his conference and I was just a black girl alone, but the two of us together would inevitable provoke some demeaning remark or commentary.

In those early years, some of our biggest fights happened when we were on holiday together, in our travels navigating spaces where one of us was inevitably a minority. Touring, the imbalance in our relationship - he the rich, white foreigner paying for everything and me - the black student with him - made me uncomfortable, hyperaware and hypersensitive. Conversely, my reactions were like an accusation to him - how can you enjoy this? How can you be so oblivious? How can you put me in this situation? Reducing him to just another white exploiter, conqueror, taking what he wanted, enjoying without thought, Africa, his playground.

Botswana, 1989, Fabio at the wheel of the second-hand yellow Laser that we had bought from a Rhodie in Bulawayo. The owner’s Ridgeback had barked relentlessly at me while paying Fabio no attention at all as we walked up the driveway to inspect the car. The Rhodie had to keep a tight hold on its collar as it kept lunging at me. It was a well-known fact that Rhodies trained their dogs to ‘smell’ out blacks.

We were tourists in those days before google maps and navigation apps; there was no telling what surprises or hazards we would meet on the journey. We travelled with a Lonely Planet guidebook and maps. Fabio would map out the route - the major roads, secondary roads, tertiary roads (highlighting them in different colors). I was in charge of navigation and I was not very good at it - I battled with the maps as I folded and refolded them until they tore at the creases. We have a whole collection of these maps and I have just had the greatest idea to have some of them - our greatest hits, as it were, framed, as a wedding anniversary gift to Fabio. And we relied on the cars’s mileage rather than the rare sign postings in the bush to tell us where we were. We never knew where exactly we would end up after a long day’s drive, and so we never made hotel reservations ahead; we had no mobile phones and our planning happened day by day.

The lodge was one of those delightful surprises and Fabio was all for splurging out on its luxury for the night. We had driven from Rusape, and over a thousand kilometers later we had chanced upon it on the banks of a river in the Chobe National Park. We soon found out, by the pictures in the lobby, that Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton were remarried in this exact lodge in 1975. Standing there in the lobby, I was overwhelmed with discomfort. All the guests were white. All the servants black. I was the only black, non-servant, person there. I felt that eyes were trained on me, judging me from every quarter. I am not sure if that was true or not. I told Fabio that I didn’t want to stay.

Driving out of the lodge he said why did I have to make everything so difficult. He was angry. He was tired. We had done over a thousand kilometers in one week, and he was the sole driver. The laser wasn’t a four wheel drive and we had been pushing it on dirt roads. I had stolen his joy. I felt like a child who had thrown a tantrum. Back then I couldn’t find the words to articulate my unease so it made me look as though I was ungrateful and being churlish. Or maybe he did know what it was but he wanted me to let it go for a moment and just enjoy the treat, leave the politics out of it, in a way, pretend I wasn’t who I was.

It was a pair of mating elephants, right in the middle of the dirt road, that saved us then. We saw them from some distance. Fabio drove slowly, and then stopped about twenty meters from them. It is quite a sight to see a bull elephant mounting an elephant. We waited. Fabio and I looked at each other. This was quite something we were witnessing. I don’t think we had thought this through. What if the elephants noticed us, got enraged and came charging, but I don’t think it occurred to us then that that could happen. We were often reckless that way, those days of our youth. We just watched. Fabio took my hand, squeezed it. We waited. And then they were done, and they moved into the bush, not at all interested in us.

We lived for four years in Bogotá. I loved the city. It was vibrant and chaotic, and the machismo which could be threatening was often comedic as when a dance floor judiciously cleared out, giving due reverence to a pint-sized dynamo hurling his six-foot beauty queen from one end of the dance floor to another to the pulsating rhythms of salsa, but I loved it most because it allowed Fabio and me to exist without the censure I felt in almost every other city we had been to. I was not an object of desire there. Had Fabio perhaps looked more like a gringo, the DEA agent type, and had as his girl, a Mestizo Colombiana, that is, a girl whose features spoke of European and Amerindian ancestry (the largest ethnic group in Colombia), then I suspect there would have been hostility, trouble. A black girl wandering the streets of Bogotá with an olive-skinned man was a peculiarity but it was not threatening or enraging.

There was too in Bogotá the constant threat of violence. Fabio and I would often go to the La Candalaria district, the artsy 17th-century centre of the town, to the movies or the theatre, or to a bar. We would come out sometimes, in the early mornings, flag a taxi on the deserted streets to take us to the northern suburbs where we lived. Nothing bad ever happened to us. But it did happen to a colleague of Fabio’s. He got into a taxi after a night out, the taxi drove for a bit and then stopped at a corner, two men jumped in, sat on either side of him. One of them pressed a gun at his side. The taxi started again. The men asked him where he was from. He was Argentinian but he had his wits about him - he said Uruguay. If he had said Argentina they would have killed him.

There is an intense rivalry and animosity between Colombia and Argentina. Colombians think that Argentines are full of themselves, while Argentines think of Colombians as campesinos, rural folk - one of the greatest days in Colombia was when the national soccer team beat Argentina 5-0; we were out on the streets of our middle-class suburb when people started shooting in the air in wild celebration.

The taxi drove off the tarred road onto gravel. He thought then that he was certainly going to die, they were taking him to the ditches of the south where bodies were dumped - it didn’t take much to upset someone in Colombia - sicarios, hired killers, could be had for as little as one hundred dollars. The car stopped. He was pushed out, told to strip. The men took his valuables and clothes and left him there, naked. He stayed there in the night, waiting for the men to come back, kill him. But they let him live.

Fabio thinks that my blackness saved us, him, from a number of near tragedies. They took me for a morena, or a negrita, a local, probably from Cali or Cartagena. My blackness, which had worked against me in Cuba, worked for me in Colombia, kept us safe. And perhaps it saved us in Zambia too when, just entering Lusaka, we were suddenly cut off by three military police vehicles and bundled into one, rifles pointed at us. We were interrogated for several, terrifying hours in separate cells; they believed that Fabio was a South African spy, taking pictures of Zambian infrastructure to send back to the apartheid government. They asked the same questions over and over…Who was I? Who was the white man? Why were we in Zambia? Why were we taking pictures while driving? - until, finally, we were released - the roll of camera film having been developed - there was no ‘infrastructure’ on it at all; we were who we said we were, boyfriend and girlfriend on a tourist visit to Zambia, behaving somewhat foolishly in a nervous country. Shaken and shattered, we drove away. We laughed nervously - in parting, several of the soldiers had commented on Fabio’s jeans and boots, had asked him to send them each ‘gifts’. We wondered how it would have been if Fabio had been alone, if they might have roughed him up immediately to get a confession out of him, with no thought of his possible innocence, if I being there had given them pause.

Whenever there is a news article about some young traveler who has got caught up in some trouble in a city or country that the State Department had warned against traveling to I have noticed that the first instinct of many people is to ask, well, what were they doing there, they were warned. I remember when I was young and death, its possibility, was never in the equation, even when I lived in the most dangerous place in the world - I was reckless and got away with it - I very well may not have. Sometimes just plain stupid, as when Fabio and I took a long walk along the Zambezi river, and only much later I understood that the occasional splashing sound I had heard by the riverbed were crocodiles. I can feel only compassion.

New York, the first few months, I was nervous, despite now being silver-haired and no longer a girl, of holding Fabio’s hand in the street. I had this still residual fear of judgmental, hostile glances. Was I ashamed or embarrassed to be with him? What was a sister doing with this white man? I think too, when alone, people see me, because of my short, natural hair, as someone who is right on with their blackness, so when I’m with Fabio it is as if there is an incongruity. But, after a few months, I realised that these were my projections. Mixed-race couples are still not so common, even in New York, but I think we are too old to be of any bother to anyone, to illict strong feelings - and perhaps age acts as a testament - look, here we are, we were/are the real deal, not some ‘jungle fever’ experiment.

Travel has brought us close together, all those years before the boys were born when it was just the two of us, joy, laughter, tears - I first saw the sea (Malindi, Kenya), snow (a doorway in England), a real, live author (Gabriel Garcia Marquez, at breakfast in Cartagena), a decorated Christmas tree in a living room looking just like the ones in movies (Nonna’s place, Rome) with Fabio - in foreign lands we have held fast to one another, defined and redefined who we are together.

On my recent visit back to Bulawayo, while helping my mother clear out her bedside drawer, she handed me a manila envelope, inside I found postcards that I had sent my family back in Bulawayo, the first one from Harare when I had just started university, to tell them that I was safe and sound in the ‘too fast’ city of Harare, the rest - a chronicle of my journeys and adventures with Fabio - I took the postcards outside, under my tree in the yard, and went back, back to our young selves…

– A canoe trip on the Okvango Delta. ‘Reeds, Reeds, and more reeds’, was our mantra as we glided on the water channels of the swamp over five days in the mokora, the traditional dug-out canoe, camping each evening and waking up before sunrise to an early morning walk where we spotted flocks of flamingoes, buffalo, doing it all while suffering from a searing hunger, because Fabio, insistent light packer that he is, in Maun, had casually flung in tuna cans and pasta shells, one 150g tuna can a day, and three 500g packs of pasta into his backpack. By the second day our provisions were gone because I foolishly believed there was more. The only thing we had left was salt which our guide made use of, seasoning his freshly-caught fish each evening. We asked him if we could have some fish and he said no because it was all he had, and he needed the protein to canoe us along the delta. For, I am embarrassed to say now, we had booked a safari trip that included being canoed by a local who was very thin and had to lug the two of us plus rucksacks until we reached the day’s camping ground. Along the water, we would pass other canoes, and under my conical straw hat and looking up from The Master and Margherita I would feel a sense of discomfort (shame?) as I saw an overweight passenger(s) blissfully asleep. I had become that kind of tourist. We begged our guide to canoe us to a hotel. We had hope that he understood, because we trekked along the delta and stopped. We had reached it, he said. We looked around us. Nothing. And then we saw where he was pointing. Across the water. Far away, a building. Food. And it was out of reach. At least we had juice. For the remaining days we survived on boiled water with a sprinkling of pasta shells. When we finally arrived back in Maun, we went to the nearest restaurant and ordered just about everything on the menu. I have a picture of that trip, the canoe guide flinging his torn net into the water. What he must have thought of us, demanding his food, his meagre rations. If it gave him some satisfaction to see us suffer, to have some compensation for the demanding work he did, if he found that work demeaning, rowing us, our privileged selves.

Before the hunger set in there was the silence, the utter peace of it… an enduring silence which was immense and beautiful. On the canoe I read, and I could not have picked a more glorious book than The Master and Margherita for this trip which I would fish out from my army-style backpack and, leaning against it, read the dreamlike story from Russia. I have the very same battered copy on my bookshelf and looking at it always brings back that sometimes surreal trip on the delta when hunger put me in a semi delirious state by the final day, when the water and air shimmered and became one, and there was the devil, the talking black cat, the assassin, the beautiful naked witch, the writer in the asylum, Bulgakov’s magic-realism novel slipping in and out of my consciousness, as we glided on the water, reeds, reeds, and more reeds.

-A night driving aimlessly in the mist, looking for the family of the lodge manager in Lake Turkana who had graciously given us his room to spend the night since we, as was our custom, had made no reservations at the lodge and it was fully booked - unable to find the homestead we had simply parked the jeep on a patch of grass in a field, a meadow. In the morning, waking up to the sight of primary school children peering into the car, their faces pressed against the glass. They told us where the homestead was. It was like a dream - flickering my eyes open to find wide-open eyes staring back, framed by hands on the glass, wet with dew.

We spent two days with the family in the lush countryside as if we had come upon a lost Eden.

- In a desolate stretch of landscape, en route to Namibia, in our totally unsuitable low-carriage Laser, getting stuck in the sand, the wheels getting deeper and deeper in the sand bed the more Fabio revved the engine. Finally giving up. A candle placed on the roof top, its single flicker in the dense night. Suddenly, coming towards us, flickering of lights, a vehicle. Fabio blaring the horn. The vehicle, a truck, stopping, then going off the road, ahead of us, stopping again. Men coming out. Fear. We are alone. Bandits, and a war across the border. But the men are angels. They haul out a rope, attach it to the car, pull us out of the sand. Go off ahead, the men say. This is the worst bit. You’ll be fine. But we are afraid of the possibility of getting stuck again. We follow the men, back to Maun. Three more times we get stuck, the wheels spinning in the sand. Three more times the angels alight from their vehicle, pull us out. Finally, on hard earth again, we want to thank the men properly, offer to buy them beers, but the angels, their truck, has disappeared into the night.

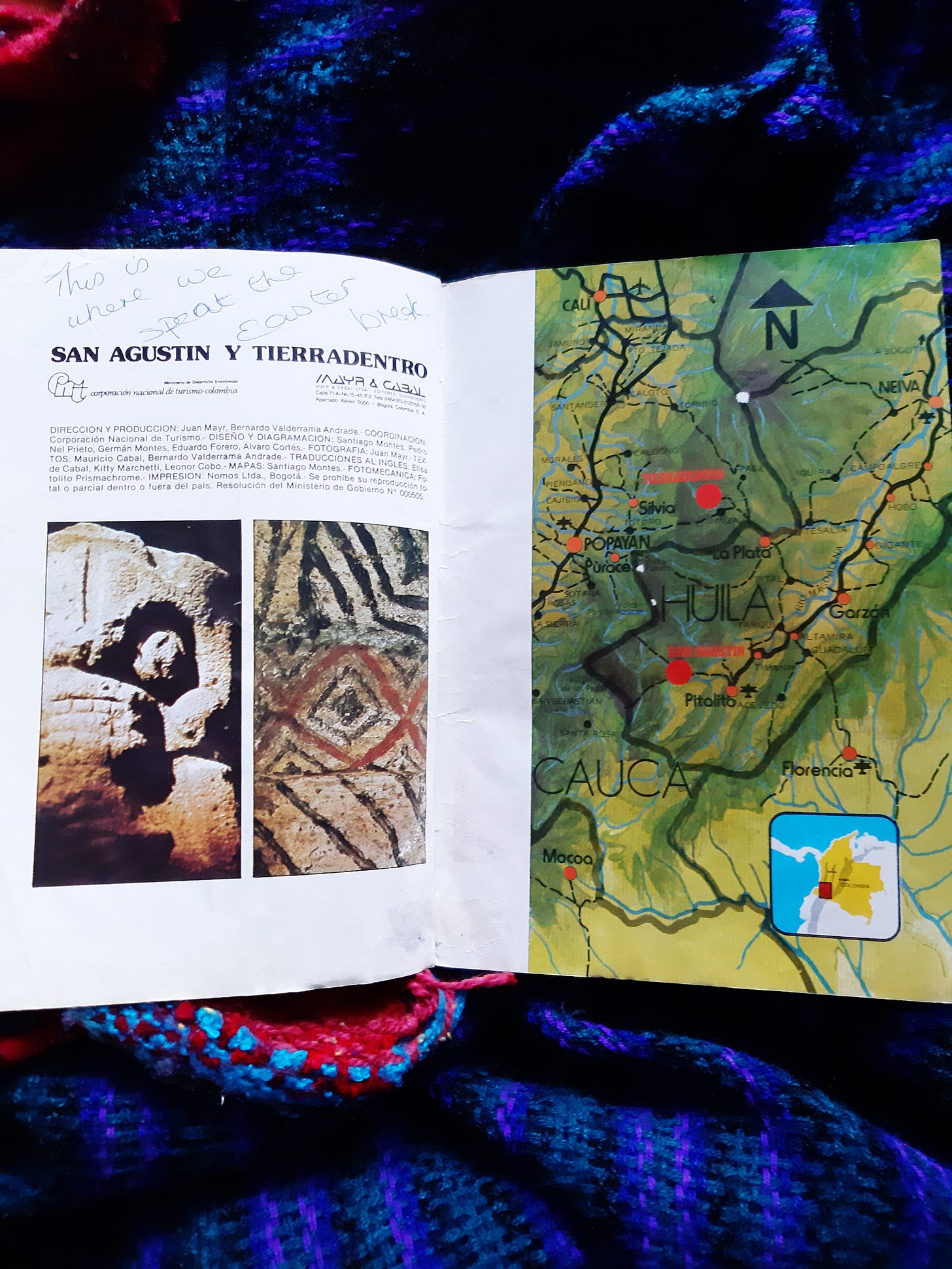

– Tierradentro, San Augustin…

long before they became safe enough for tourists to visit, Fabio and I drove out of Bogotá to a possible hijacking, kidnapping. We left without telling anyone where we were going. If we had disappeared no one would have known in which direction to look. It was the time before cell phones. I tell my boys now don’t behave like mum and dad. We rented the car because we didn’t drive in Bogotá. Usually, on week-ends, we would take the bus to go to the villages of Villa de Lleyva or Tenza, the vertiginous hillside roads combined with the reckless driving, always leaving me sick, but it was worth it to reach the oasis of these 16th-century villages with their cobbled streets, plazas, and well-preserved white-washed villas where life was ‘mucho más tranquilly ’ than in Bogotá.

We drove out on the highway, the Autopista Sur, a craziness that left us barely alive, even Fabio, a veteran of the chaos of Rome roads was a novice here, each driver made his own lane, abided by his own rules, fueled by a feverish machismo which seemed to reach its zenith on this early morning as we set out to escape the city. Several times we were almost crushed by trucks, whose horns blared angrily at our perceived transgressions, in not moving the hell out of the way fast enough. Vehicles seemed to spring out of nowhere into our path, honking and blasting their fury at our impertinence. It had been a long time since Catholic school but I sent up a Hail Mary.

- Colombia, 1993, land of guerrillas and narcotrafficantes, and we were going off off the beaten track. Tierrodentro, in the south-west of Colombia in the Andean's central cordillera, not yet a UNESCO world heritage site, too far off in the wilderness: the tombs were in the heart of Colombia’s red zone in the region of Cauca where there were bloody battles between fighters from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the Colombian military and right-wing paramilitary groups. Kidnappings and ambushes were common, but we were young and reckless, and not saturated by 24 hour news and the internet, and we didn’t read the papers very much. Only much later we realised how foolish we had been. When we got back to Bogotá. we learnt of a bus that had been ambushed and the passengers kidnapped on the Pan American highway, hours after we had just been on it.

After the nine hour, death-defying car ride, we drove to our lodgings in Tierradentro - a sprawling expanse of a hotel which seemed to arise from nowhere in the jungle. We checked in, and went to our room, but we did not even unpack our bags. Thirty minutes later we had checked out again. I was spooked by the hotel’s emptiness; we appeared to be the only guests there. I imagined that it was possibly a narco-trafficante, money-laundering scam, something I now imagine along the tv series The Ozarks. We drove around aimlessly until we came upon a narrow, dirt road and on one side of it was a simple guest house, run by a family. We stayed there for a week, a delightful time where it felt as if we were out of time, no radios, no television, just the two of us in this isolated paradise, each day a lazy, glorious wonder of a myriad of chirping birds flitting from one woodland area to another as we walked the trails, crystal-clear streams, waterfalls, nature so breathtaking that even I, a city person, was enchanted by it - a particular highlight was walking across two cliffs on the most flimsiest of rope bridges, as a river flowed below.

It occurs to me that an earlier draft of The Rhodesians/ The History Makers (unpublished) had a story line which was my attempt at magic-realism: here, the paradise of Tierradentro is given a sinister edge as guerrillas attack and kidnap a group of archaeologists; a battalion of Colombian soldiers is in the jungle too, one of the young soldiers, the son of a local drunkard, Orlando, who gets visits from the Holy Virgin Mother - this draft is called ‘Dreamscapes of the Virgins’ and I am rather fond of it.

Each morning we were woken up by the squawking of parrots, and when I drew the bedroom curtain I could see the sprightly old man (the abuelo) climbing up the orange tree to get oranges for our breakfast. We would have breakfast on our verandah and then set out to the archaelogical park. A guide collected us from the tiny visitor’s centre and we walked up the steep hillside to the tombs.

The guide unlocked the trapdoor and, peering and squinting into the dank darkness, we followed him on the steep, narrow, spiraling stairs as his torchlight flickered against the walls. It was claustrophobic and nerve-wracking, one slip, one wrong footing on the stairs that had no railing would send us tumbling into the dark (cuidaido, cuidaido, he kept whispering).

This was one of the deepest tombs, seven meters deep. Finally we were in the burial chamber. It was 12 meters wide, the guide said. 600 to 900 AD. The walls, pillars and free-standing columns were decorated with motifs. It was a sight to behold, all this that had been fashioned so many many years ago. And writing this now I come to the realization that Tomas, my archaeologist in The Rhodesians/The History Makers, must have put his roots in my unconscious here as I wandered in the excavated depths of the long dead.

What if the guide had not been an amiable fellow but one full of resentment at the extranjeros with their easy dinero - what if, he, having taken us down there, had suddenly disappeared with his torch, leaving us underground, closing the trapdoor, locking it. What if he had somehow got hold of our possessions. Left us there to die, rot; we were the first visitors in a very long while and who knew when the trapdoor would be opened again. It is the What if, the alternative reality that becomes a story, a novel, a book.

We drove on to San Augustin, about five hours away. We made our way through the roads of villages, that existed like characters in a Gabriel Garcia Marquez novel - La Plata, San Andres de Pisimbala, Pitalito, San Augustin.

The largest group of religious monuments and megalithic sculptures in South America stood in the wild, spectacular landscape of forest, cliffs and ravines. Gods and mythical animals, human forms and animals - crocodiles, bats and jaguars - abstract and realistically rendered on massive stone sculptures, works of the Andean culture of the 1st to the 8th century. There were alters. What/Who had they sacrificed there?

We spent two nights in the village of San Augustin, which was full of all kinds of hustlers - it reminded me of those wild west towns you saw in movies, an element of danger embedded in each interaction.

One afternoon, while walking back to our hotel, we were waylaid by two men who told us a merry tale of maravillosos artefactos - vasijas intactas, venga, venga - marvelous artefacts - intact pots - come, come . They led us, through a warren of streets, to a dusty, dimly lit room full of pots and statues, dug up, they said, from archaeological sites. They said they would give us a ‘certificate of authenticity’. Fabio and I declined, and left. I wrote about this in The Rhodesians/The History Makers… except then the young couple do not leave the dusty room intact… they are the victim of a devastating brutality… fiction is autobiography, it is the what if?

So much could have gone wrong on that trip, but instead it was filled with magical moments.

We are empty nesters now. After years of traveling with our two boys, it will be just the two of us once again.

While walking on the Esplanade during those months of lockdown Fabio and I suddenly thought, hey, maybe we should start a travel vlog, when this is all over. We had been sucked into the world of Youtube vlogging in the long hours spent in the apartment. We saw all these young, excited couples, hopping from one place to another, recording their experiences and putting it out there on YouTube. Some of the videos were very polished with drone footage and what looked like professional editing. Some had sponsors. Sometimes the couples were invited to luxury hotels to promote them. We were engrossed by the travels of an American couple who had the goal of visiting one hundred countries… it was fascinating to see their progression from exotic locales pre-pandemic to flying home and continuing their adventures in a camper van in America. Fabio was so excited by the idea that he researched all the video and camera equipment we would need. We would be groundbreaking. There weren’t any middle-age travel vlogging couples, at least none we could find. It would be fun. Our enthusiasm for the idea didn’t last long. The travel vloggers' trips seemed so well curated, so carefully managed and produced that we didn’t think we could compete.

We sit on a bench in Union Square. The anti-vaxxers are out in full swing by the Abe Lincoln statue. They’ve set up their table. They have a microphone and a hailer. China! China! China! Wuhan! Bill Gates! Microsoft! Diapers! Chips!

Before Covid, disease and death while traveling, exploring a new place, seemed like localized, sporadic events: a badly thawed out/microwaved, most likely expired, vegetarian lasagne eaten in a remote part of Scotland, excavated from the depths of a freezer when you said you were vegetarian, leaving you sick for days on your honeymoon, a bout of malaria in a remote part of Zimbabwe, leaving you delirious in the back of a landrover, Fabio driving frantically to get you to a hospital, seeing flying white horses in the rushing night.… bad timing, bad luck… But now, wherever you go, will be the specter of this airborne virus… the magic moments of travel a bygone era.

But, wherever we may go, however we may see and experience this new world, it will be the two of us together, as it has been for so many years.

Coda: Extracts from The Rhodesians/The History Makers/Dreamscapes of the Virgins (unpublished)

Bogotá, Colombia, August 1992

Isobel

She lay on the bed for days and days.

There were people who kept coming up to her, people whom she thought she might know; that old woman, hadn’t she seen her gazing out a window in a bus, the virgin mother dangling from the rearview mirror, twirling her hips, garish lips on the gear box, radio blaring, pegando el pecho, pegando el pecho…

Names floated up to her: Constancia, Orlando, Romario, Miguel, Alejandro...

She didn’t know if these people were dead or alive.

Sometimes they would come alone.

Sometimes they would congregate there together, seeping into each other’s flesh, their mouths opening and closing all at the same time so she couldn’t tell where the words came from but she had the strongest feeling they were all telling her the same story.

They wanted her to be ready for when she woke up.

Sometimes, overhead, she heard helicopters, and when she looked up propellers were rotating round and round over her head.

The names and words shimmered as though she were in a desert in the heat.

Which was not so; she was in the jungle, it’s where they took her.

She lay on the bed for days and days.

One morning she woke up, the taste of dirt in her mouth.

And something else.

He was standing at her bedside, the stumps wound up tightly in old cloth. She didn’t ask him what happened.

She already knew.

In her mouth, dirt and blood. She wanted to spit it out, to be sick. But she swallowed. The people who had come visiting had told her everything, buried the awful truth deep inside her.

She kept their story, which was really his, a secret.

She had to take care of him.

She knew what had happened, all of it.

Tomas

He had woken up this morning with dirt in his mouth; the taste of it so strong, the feel of grit on his tongue still there so that he had actually got out of bed to check in the bathroom mirror.

But, of course, his mouth had been clean.

He hadn’t been burrowing about.

He knew what it meant; a longing for his past life, his hands working away at the ground, patiently loosening soil, sifting through it, working to unearth whatever it was that was hiding below.

Perhaps he should start thinking of going back to field work: getting his hands dirty. As it were.

He had visions, images of his hands.

The hands, just lying there on the stone floor.

When he woke up he was not gasping for breath, shouting or crying out, his body was not drenched in sweat; nor did his eyes snap open into the darkness into which his hands had vanished.

No, there was none of that.

He did not disturb Isobel.

His eyes simply opened as though he had merely been thinking with them closed.

He felt perhaps a bit thirsty or hungry.

He would carefully get out of bed, make his way to the bathroom or toilet.

There was no despair or rage, just the certain knowledge that the hands were there in his sleep.

He was grateful.

Once, the hands were suspended in the air, held there it seemed by string, no, something tougher, less yielding, wire then, like a Salvador Dali painting.

He fixated on certain details; compared the hands to what he remembered, what he thought he remembered, moles, bits of hair, crinkles, scratches, a ring.

There were things that he could imagine, but not quite.

How did you conjure up touch: reaching out, grasping, grabbing, holding, the nerve endings under the tips of his fingers, working. He had forgotten how that felt, perhaps not forgotten after all, just that the remembering, he knew, was nothing like how it was, how it had been. Hot Cold Hard Soft Smooth Rough only words now when before they meant he knew some secret about the things in his hands.

The image of his arm hanging askew from his body felt almost visceral, as if he could really feel it there which was the strangest thing, for it was the first time in a long while he had had that sensation, the ache of his limb, the searing pain, how exquisite it was, to feel that.

He looked down at his hands. The steel claws that were his fingers.

He knew how much they infuriated Isobel, these hands that he had finally settled on after weeks of trying on different types in the clinics in Lausanne and Zurich. He also liked the fact that they had been used before, a donation; they had been worn in, that they had a history.

Did she suspect, guess what they were about, why them and not the sophisticated prosthetics now available on the market?

In his desk he had a drawing of “A man without arms seen by Ambroisie Pare”, a photocopy from a book that he had bought at the Sunday morning flea market. How flustered the vendor had been to find himself selling a book about Freaks (The History and Lore of Freaks by CJS Thompson) to a man with steel claws. Under the picture he had stuck Ambroisie Pare’s description of this armless man who was about forty years old. “ … who although he wanted his arms, notwithstanding did indifferently perform all those things which are usually done with the hands, for with the top of his shoulder, head and neck, he would strike an axe or hatchet with as sure and strong blow into a post, as any other man could do with his hands, and he would latch a coachman’s whip that he would make it give a great crack by the strong retraction of the air, but he ate, drank, played at cards and suchlike with his feet.”

Every time his eyes settled on the picture he smiled at the rather cavalier figure the man cut: the tousled hair, the splendid moustache; the whip held jauntily along the shoulder, nestled by the chin, its tail lashing up the air; the man’s robes flowing over his body like a Greek god; the blade of the hoe struck into the ground, a pair of dice, some cards and what looked like a spoon sprawled about his feet. Here was a man of lore and here he was, Tomas Olsson, a man of the Future, that Brave New World, where the genetic code had been broken, very soon a human would be cloned, and who knew how easily then it would be to outfit oneself with new parts.

Later on Pare had written that the man came to a tragic end. He was taken for a thief and murderer, hanged and fastened to a wheel.

But, he had too a still from the movie The Best Years of Our Lives of a dapper looking Harold Russell playing piano with his hooked hands. It had moved him when he had found out that the prosthetics were real: Harold Russell was indeed a double amputee, having lost both his hands while working as a demolition instructor during The Second World War. He had won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor. Tomas had watched the movie several times.

Sometimes a student asked about the hands.

One late morning in August, over five years ago, in a patch of South American jungle - how the stone floor so easily, so quickly became the undergrowth that he had whispered in Isobel’s ears those days she lay asleep, a kind of self-induced coma, paralysis the doctor had called it, in a hospital in Bogotá, airlifted they’d been from Tierradentro. He stayed there at her bedside embedding her with another version of horror that was a fairy tale, her father there too, listening. How easy it was really in this land of a thousand years of solitude, of magic realism, where reality could be so fantastical it could only be imagined as fiction, of its drug lords who were jailed in palaces on hill tops with their own private zoos and beauty queens.

An archeological dig gone wrong.

Guerillas.

He was surprised how smoothly the story tripped out of him.

His story told them that archaeology was a serious business; it entailed risk: you couldn’t go about digging up burial grounds, poking around in graves, without expecting consequences. Either the dead demanded payment or it was the living. Sometimes both.

He was telling them a story, just a story. A thousand ways of telling it, and he chose this one.

Sometimes he felt as though he was hearing it for the first time. His particular story. His slice of reality.

For, of course there were things that he left out, Isobel for one. They didn’t need her there.

Isobel’s missing days. Thirteen days. And he gave them to her. ‘You were in Bogota, teaching, remember…’

Isobel

The cathedral was nowhere near as grand and foreboding as she had thought of and imagined. The cathedral she remembered might have been plucked from the spot where it should have been and replaced by this less spectacular affair. She was hurt as though someone had intentionally perpetrated this bit of subterfuge. As she looked at the building she wondered if the treachery, after all, was not all her doing; she was no longer looking at it with a ten year old’s eye - age and experience, travel, had scraped away the layers of wonder, stripped her of the awe that she had found in the stone, the darkness (she had remembered it as dark and yet here she was bathed in a pool of sunlight which came through the stained glass windows).

She had seen bigger, grander sights.

As she walked she studied the Stations of the Cross.

Had she ever found these tragic? Was the fact that they left her unmoved, evidence of her not believing anymore? She viewed them now as a bit of folklore, not too well executed; if she was being generous she might call them naive.

And there was Jesus, beloved Jesus, nailed onto the cross, his beautiful hands bloodied, and she stepped closer, closer still, she must look at those hands, see them, feel them, she must taste the blood on them.

And then she was no longer there, here, but in another church, cathedral, and the fragments came to her and were gone before she could hold onto them. As though they were dreams of dreams. A priest coming to her. A prayer for Tomas who lay in a hospital bed in a village in Colombia, the Virgin Mary, looking down on him from the far wall. And then she felt herself sink into the ground and then lifted off it by hands she didn’t know, want, hands tightening around her and Tomas in the room, in this other room, terror in his eyes… around her them, the smell of earth, clay, pots... and the men were gathered around him, them, and she felt the weight of something, cold and hard in her hand, the men pushing and thrusting it into her, and Tomas there, no, not there, Tomas in the jungle, in the room, and she felt herself slip onto the stone floor of the church, the cathedral, bless me father for I have sinned... the machete clattering onto the floor… blood dripping onto the wet earth…. A voice in her ear… puta… the fall of hands… puta… and as she lay there on the cold stone she could hear the voices whispering to her, and the voices became one, Tomas, at her bedside whispering… Orlando Cruz Morales was not a man to see visions… and she looked over him and saw the Holy Virgin Mother on the wall, smiling.