This is a story of a hero, but it took me a long time to figure out who the hero was and how to fix things - so begins Peace and Conflict, a novel which I had the most absolute fun and joy writing.

Like The Boy Next Door, Peace and Conflict had a real event as its inspiration, its trigger: one afternoon, my sons were scrambling up the stairs to our apartment when suddenly they heard a very loud, gruff, angry voice from behind a door in the entresol level, shout, ‘Taisez-vous. Ce n’est pas la rue!’, my son’s yelped and fled for their lives, huffing and panting when I opened our door to safety, and from there was born the legend of the entresol, Robert’s in-between place, and the one-eyed monster lurking behind its doors, otherwise known as Peace and Conflict’s Monsieur Renoir. Nothing like that had ever happened in our building. Once again, my imagination took flight, not knowing the occupant of the entresol apartment, and what lay in his lair, his anonymity allowed for the creation, in my very own lair, of a monster, in the eyes of a book-loving, always-thinking, ten-year-old boy.

I don’t know why but I twisted my neck round. It was the first time I’d ever seen even a bit of Monsieur Renoir. And that bit didn’t look too good. His head was stuck between the door and the frame. His eye was blazing right into me.

At the 2010 Gothenburg Book Fair an interviewer shared with me that another writer from Africa had said that she could not publish just any novel, it had to be ‘African’ and African as what her publisher envisioned African to be; she then asked me if I felt the same way. I answered, ask me that in a few years.

In Peace and Conflict (2014), I did manage to stretch a bit what I could publish then as an African writer.

The novel is centered on a middle class, multicultural family living in the very affluent town of Geneva in Switzerland (right there, that’s an example of the ‘stretching a bit’ part) and the adventures of the youngest son, ten-year-old Robert.

My character are very real to me. Robert lives, breathes. He sees, hears, acts. He thinks. He has a voice. And because he has a body, a heart, a mind, a soul he inhabits space, time. Geneva is his home, his playground, the location of his escapades as he tries to solve the mystery of his grouchy neighbor, Monsieur Renoir, and the Victoria Cross medal mysteriously left on Robert’s doorstep, a mystery which catapults him from his life in Geneva to Kenya during the time of the Mau Mau and the British occupation, off deep into the muddy tenches of World War II and up high in the skies with a heroic fighter pilot, all the way to South Africa and a stolen medal.

As I wander about Geneva and its environs it is Robert who is my companion, who gives me a fresh pairs of eyes, a new way of seeing the best place in the world.

There, in Parc des Bastions, just under the old town, Robert and his fourteen year old, football-crazy, mega-popular brother, with all the swag, George - he was really Giorgio but everyone called him George - play chess. It was number 3 in my top favorite places in the whole world. We had epic battles there.

over in Place Neuve - So we crossed the square, and I made sure to look up at General Dufour in the middle with his beautiful horse. He was riding off to save the Federation of Switzerland…

Up on the Rampe de la Treille… I ran up the hill and then I waited for them on the Longest Bench in the World I stood on the bench and looked down over the old city wall. The Duke of Savoy and his soldiers…

and

I ran up to Monsieur de Rochemont standing on his plinth with a document rolled up in his hand… Jean: He’s in his underwear. Mr Reynolds: don’t be silly, that’s how noblemen dressed in the nineteenth century. Philip: He looks like a penguin. Manuel: Someone’s pantsed him. And the whole class went hysterical…

Away from the old town… We drove across the Mont Blanc Bridge. The flags along the bridge were fluttering about but not so much as when it was really windy and it looked like they would snap off their poles. I looked over at Monsieur Rousseau sitting high on his chair with a book on his knee and a pen in his hand… there he was on his island, looking over Lake Geneva…

In Aigle, a medieval town in the canton of Vaud, at the flea market along the riverbank, I found Robert’s magic ‘teapot’. I looked up at the Alladin lamp. When dad gave it to me, George rubbed his hand on it. ‘Oh magic lamp form Key… whatever, I wish to be a famous footballer… you only get one wish, I said… Dad wasn’t in the room anymore, so he said, ‘It’s a teapot, you dork’.

And that makes me smile.

There is a strong African connection in Peace and Conflict. The writer mother is Zimbabwean and a thread in the novel involves the mother’s sister who is a wildlife veterinarian in Zimbabwe. Aunty Delphia and her career were inspired by a safari trip my family took to Hwange National Park, which made a huge impression on me. I wrote about the inspiration for Peace and Conflict for National Geographic Traveller

Aunty Delphia’s tree house (actually Aunty Delphia’s actual treehouse would be much higher off the ground because sometime she operates on animals underneath it);

Robert on Safari

Aunty Delphia’s beloved elephants… On another day, Aunty Delphia put drops in a baby elephant’s eyes because they had an infection. The elephant - Aunty Delphia called her Thandi - liked aunty Delphia and it looked like she was trying to kiss her with her trunk

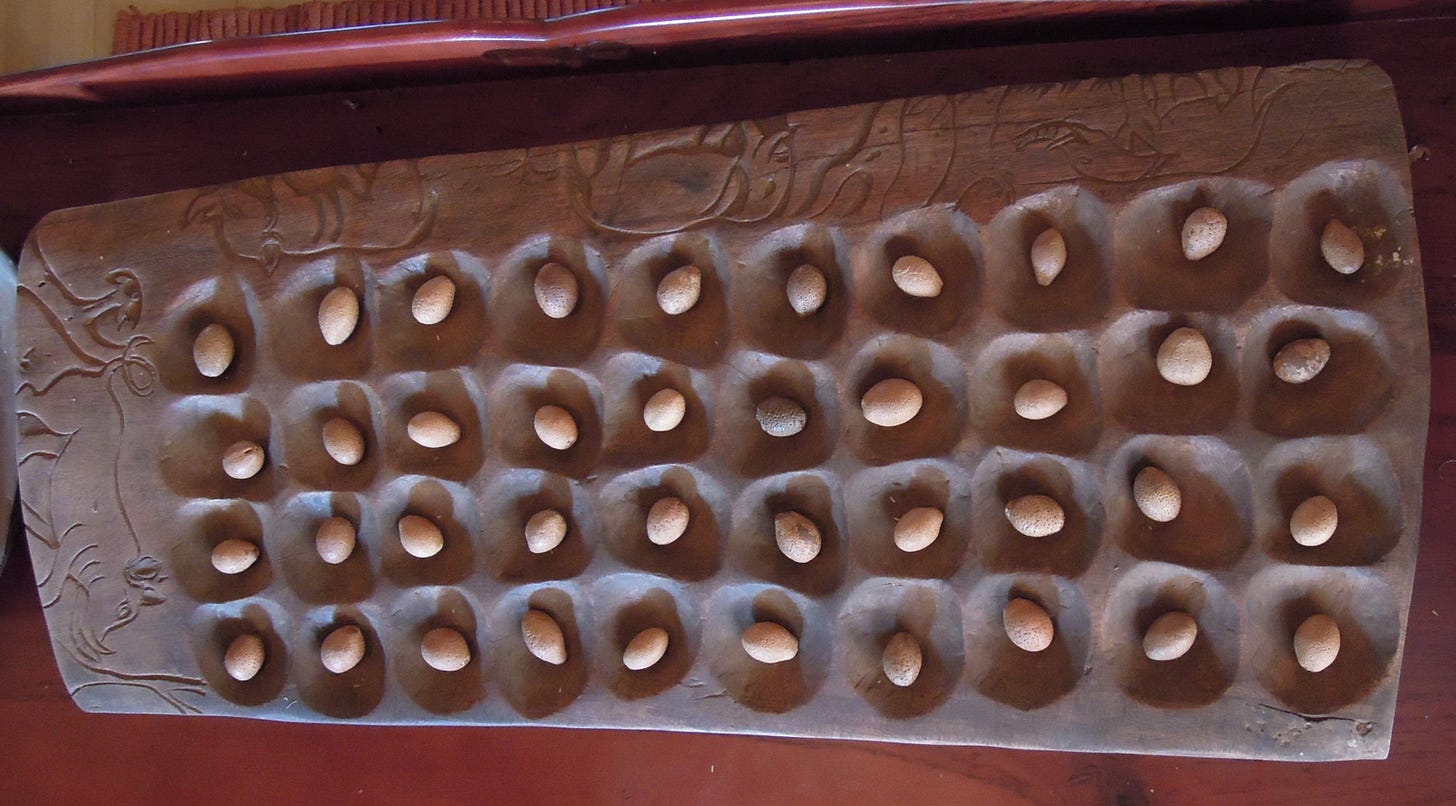

Tsoro which Robert plays with Aunty Delphia… I love tsoro. It was invented in Zimbabwe. When we played in Zimbabwe, Grandpa just scooped holes in the dirt we used stones. But he made a wooden set and gave me lucky bean seeds a leather pouch to take back to Geneva.

Peace and Conflict had a struggle finding a home. It was not an obvious follow up to The Boy Next Door (my then publisher rejected my proposed second novel, which would later become An Act of Defiance) and it fell in the gap between children and adult novel. It was not Young Adult as I understood it to mean. There was a teenager in it, George the older brother, it was not his story though. It was Robert’s, his ten-year-old brother. The novel was in his voice. So, children’s? Well no, according to how booksellers and publishers classify books, because it dealt with some dark themes it wasn’t really a children’s book. When I wrote it, there was no planning to it; I did not stop to consider, am I writing a Children’s Book or an Adult Book in a child’s voice, like say, The Room. Perhaps I should have done. But then, it wouldn’t be Peace and Conflict.

The readership for Peace and Conflict, in my view, was both children and adults. I think that the hyper-categorization of novels can be a limiting exercise, restricting the choice of books to readers - I remember picking up and reading the first Harry Potter Book, and thinking, at the end of it, why are adults reading this book? I didn’t get it. I still don’t get it. The other Harry Potter books I can understand because they seemed geared for the readership as it grew older, but the very first one?, it was clearly a children’s book, but somehow hundreds, thousands, millions of adults connected with it, or escaped with it to Pottersworld, who knows what the magic was, is.

My point is that classification, helpful as it can be in deciding where to put books on limited shelf space, can restrict what is available to the reader - they may feel embarrassed about lifting a book from a particular category in the bookshop, and therefore never wander there. Adult or children’s- who is to decide and how and why.

The cover of Peace and Conflict puts it clearly in Children’s book territory with its cute, child like drawing. Again, we come to the question of marketing.

Recently, a work colleague of Fabio’s sent him an email which made my heart soar. …Was thinking of you and Irene this week. A. (now 10) is reading Peace and Conflict for the third time. He says, “I really like this book. The boy is just like me.”

And that makes me very, very happy!

(Possibly) Robert up in the treehouse with (possibly) his mum.

I had such fun writing Peace and Conflict that I wrote two sequels to it: Growth and Change (unpublished) and Force and Motion (unpublished).

My then agent wrote an enthusiastic, albeit unsuccessful, pitch for Growth and Change to my then editor:

I’m delighted to be sending you Irene Sabatini’s new Robert Sartori novel, GROWTH AND CHANGE. He’s still a charmer, but life is getting more complicated: he has to go to Middle School, he’s just lost his best friend Jin to Facebook, and some creepy guy who looks like Frankenstein keeps turning up everywhere.

More worryingly, someone has been targeting Robert’s brother on the football pitch, calling him a foreigner. And there were all those posters for the referendum. The ones with the white sheep kicking out the black sheep from the map of Switzerland. Doesn’t Geneva want Robert’s family anymore? It’s still the best place in the world – isn’t it?

There’s the same sense of playfulness and fun to Robert’s voice, and a great mystery to solve, too, but with this new novel there’s also a new gravitas. Robert is just that little bit older, and beginning to become aware of some aspects of the adult world that he hadn’t noticed before. Much of Europe is having to confront some pretty unpalatable views among its voters, and Robert’s straightforward naivety tackles the subject with warmth and charm.

Can’t wait to hear what you think.

and this was the blurb for the Bologna Children’s Book Fair (again, no takers):

Growth and Change, a boy’s tale

Eleven year old Robert Sartori, citoyen of Geneva, with his very particular, inquiring view of the world (questions, questions, questions), is thrust into the minefield of Middle School where something as simple as the kind of backpack you carry can mark you out as a social outcast, where friendships can be sabotaged by fads such as zombie warfare and Facebook and where puberty lurks in every armpit check. And home too has its own changes and complications: mum is pregnant, a baby sister threatening Robert’s status as the ‘chouchou’ and his older, star football player brother, George is embroiled in a dangerous rivalry with another footballer.

Following on the mystery of the stolen World War One Medal, Robert stumbles on another mystery when a former neighbour’s housekeeper is found dead (murdered?) in a villa on the lakeshore. Robert, together with his best friend Jin, and their new Swiss sailing buddies, Luc and Anne Marie, embark on an adventure that will culminate in an epic crossing of the lake by Robert from the land of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to a very real and alive monster on the other side of the lake. Robert’s wits and bravery will be tested all the way and new; unexpected friendships and alliances will be forged and the long ago heroes of his beloved Geneva will be there to help him every step of the way: Rousseau, Captain Dunant; Madame Stendhal....

Coda: Extract from Growth and Change (unpublished)

This is a story about monsters.

They come in different shapes and sizes.

They lived all along the lake shore of the best place in the world.

And they were all after me.

Chapter One: Au Voleur! Stop Thief!

So, Middle School was only six days away. George had told me all about it. He said that all the business I had about washing my hands the way the health visitor showed us so that we wouldn’t get swine flu, counting up to twenty really slowly, he said that I should forget about that, Middle School toilets were not a place I wanted to hang around in. Things happened in them. People got swirled in them. People had their pocket money stolen. Or their homework flushed down the toilet - remember that blockage when all that goo went spilling out the hallway, well that was someone’s science homework and a whole lot of other stuff. So, Rule Number One was, never never wash your hands in the Middle School toilets. Never. This made me really nervous. But then I remembered mum’s anti-bacterial gels - she has thousands of them - I’d pack those. Second, no smiling (the dimples) - cute was not something I wanted to have on my résumé as a middle-school grader (not that kind of cute). Third - then he thought about it - no, this is first; second, smiling; third, the hand washing, first, lose that backpack. That was my lego CITY backpack. I loved it. George said that if I loved my life the backpack had to go. I was devastated. This is a middle school backpack, said George, lifting his. It was black. That was it. There was nothing special about it. It didn’t have any secret pockets or a special place where the rain cover (fluorescent yellow) was rolled up so that you could keep the backpack dry when it rained. When I showed it to George he said, dork. His was black and falling apart. He’d had it forever.

His backpack was dope. Dope was the new swag, apparently.

I have to admit I was pretty nervous about going into Middle School. Kids you’d known practically all your life changed. I mean kids you’d known literally all your life changed. George. One minute he was just a typical kid and then, as soon as he stepped into Middle School, he became an alien. He discovered swag which, yeah sure, wasn’t swag anymore now that he was almost finished Middle School. Dope which sounded kinda dopey. So I was really worried about Jin. What if he’d changed and become someone else completely? What if I didn’t even recognise him on the first day? What if he wanted to hang out with the cool, dope kids? Last year we’d had a whole unit on PUBERTY so that we wouldn’t be completely grossed out or freak out when hairs and stuff started sprouting all over our bodies. I’d seen it happen to George so I knew what to expect, and some of it wasn’t pretty - I kept sniffing under my pits to check if they were hairy and smelly and if I’d have to start overloading George’s Axe’s deodorant on them - mum kept buying him eco-friendly green deodorant from The Body Shop because she said it wasn’t safe to spray so many chemicals into your pits - George said that stuff was for girls, he was a MAN. And Jin had kept us sixth graders up to date with Su’s transformations, Too Much Information! I kept checking to see if Puberty was anywhere near me; I kept asking mum if I was still Puberty Free.

Mum had read a study about the effects of the right backpack on children’s self-esteem. Seriously, she had. It was amazing that George and mum were thinking the same thing. What was happening?

So that’s why we were here in Manor when I could have been doing something much more interesting on the last few days of the break.

I sighed. They had so many Lego backpacks at the special Rentrée section they always set up right at the beginning of the holidays, just on the day schools closed - couldn’t they give us kids a break?! Did they really have to remind us so early that the holidays would finish and we would have to drag ourselves back to school - couldn’t they at least wait a few more weeks, days even?! I thought that it was obviously a sign - those backpacks wanted ME. But then mum showed me another sign over the Lego bags -scolaire primaire - and that was that. Good-bye, my lego friends. Welcome... the bags sucked. Really sucked. They looked just like George’s but new. George said that after I bought my bag I’d have to give it a work over. It was definitely not cool to bring a bright, shiny new backpack to school. I had to age it - fast. George said that the coolest thing I could do was to get his bag and he’d do me the favour of taking my new one...because no one ever made fun of him. He was GEORGE SARTORI - FOOTBALL HERO - SWISS UNDER SEVENTEEN FOOTBALL STAR with his own Facebook fan page, currently at four thousand and one likes. He was starting to think he could take on Christian Ronaldo’s forty million likes.

Mum took down the backpacks and tried to tempt me with all the different shades of grey and black. Really?! I wanted reds and blues and yellows but no, those weren’t Middle School colours. I wanted pockets where I could hide my spy things- tape recorder, binoculars, pen, two-way radios - George said it was time for me to face facts: there were no SPY KIDS, the whole thing was just a marketing gimmick for geeks. Was he trying to ruin my life? The tooth fairy didn’t exist. Father Christmas didn’t exist. Wasn’t that enough? Couldn’t he just leave the spy kids alone? What did he know, anyway? He wasn’t a spy was he? He was a teenager and that was just about it.

Mum kept showing me bags. How about this one? This one? This one? No. No. No. Maybe she would get tired. Maybe she would give up and we could go home and I’d take my Lego City backpack to Middle School. She was always saying that we shouldn’t be sheep, we shouldn’t follow the herd but now she wanted me to be a sheep, she wanted me to follow the herd.

“Mum-san...”

“This one, Robert.”

And that was it. She had made one of her executive decisions. It was black and grey. Just, great! The year of living dangerously!

Mum went through the list of all the supplies I needed. There was so much stuff. George was right. Middle School was no picnic. I was going to pay for all my years of slacking off in primary school.

“Let’s go and have some lunch,” said mum. “I’m starving, so is your sister.” Mum rubbed her tummy.

In January, which was four months from now, a girl was going to come out of mum. A girl. I still freaked out when I saw bumps and humps moving along mum’s stomach. That’s her hand, that’s her fist, oh, she’s kicking really hard now. Mum could even tell when she was hiccuping. It was weird. Mum said the baby liked it when I played the piano because she started dancing around in her belly and I could see her doing something like a snake. When we were at the doctor’s and the doctor did the ultrasound thing where she put a cold gel on mum’s stomach (I mean uterus - we learnt all the proper words in the Puberty talks) and then moved this pad over her which was connected to a T.V. screen and we could see what was happening in mum’s stomach; George thought looking into mum’s stomach was just gross so he didn’t come. We could see her. My sister. The one time she was sucking her thumb and that’s when we got to know she was a girl because there wasn’t a penis anywhere in sight. Or maybe it would turn out to be A Curious Case of Mistaken Identity, like what happened with George. I asked mum if we were going to call her Kioko - Key oh ko- which was what George was supposed to be called if he was a girl - he even had a gold necklace with the name on it which Nonna had made when everyone still thought he was going to be a girl. Nonna said it was a good thing he turned out to be a boy - actually Nonna was the only one who called George by his real name - Giorgio. Mum said no, we had to come up with a whole new name, I think in her head Kioko was still George’s name.

I was going to have a sister!

I wasn’t going to be the youngest anymore. I didn’t really know how I felt about that. I’d be an older brother. I think I felt good about that, but what if she was a really annoying sister? A girl with OMG’s, BFF’s, all the time? What if she made everything pink?! George was really annoyed about it; the playroo-hangout room wasn’t going to be his bedroom next year when he turned sixteen - it was going to be his baby sister’s room! The best room in the whole house and it was supposed to be George’s room next year and then mum “accidentally” got pregnant. George said it was going to be embarrassing to be a teenager with a baby sister. And he wasn’t going to baby sit and change diapers, no ways, or drive her around anywhere when he got his license. And that went for me, too.

Mum wasn’t worried about George. She said he was a softie at heart; once he held his baby sister his heart would go all gooey and melt; she’d win him over.

I used to love coming to the restaurant in Manor. I loved making up my own pizza and getting the wooden disc that vibrated and lit up blue when your pizza was ready. But no more. Those good days were over. Done. I had to watch what I ate, in other words, I was on a diet, even though mum said that wasn’t true. Anyway, I had Dr. Legrand to thank. Last Check Up, he looked at his chart (curse it) and said I was slightly overweight.

George: Fat.

George was allowed to eat anything he liked because he needed to put on some bulk. He spent most of his life at MacDonald’s. Curse my fate!

So, I wasn’t allowed pizzas, except on Sundays. I wasn’t allowed too much bread and too much pasta, except sometimes it was pretty hard to figure what too much was: mum and dad said as soon as I didn’t feel hungry I should stop eating but sometimes it was hard to know if the feeling I had was of being full or a little full or, one more bite and I might be full. And you could be full with one thing but not of another, for instance dessert. I could eat as many vegetables and fruits that I liked.

I walked past the pizza oven, the pasta counter - it smelt so good, my stomach rumbled - and dived into the salads and boiled rice and the omeletts which were okay, I guess.

I walked in front of mum, holding my tray all the way out to protect mum (and my sister) from all the people who were pushing and shoving. Mum paid and we found a table near the windows. I could see the Jet d’Eau over the rooftops.

Mum had some pretty greasy-looking chicken wings piled high on her plate. Mum was allowed to eat anything because she had ‘cravings’ which was what pregnant women had all the time. Apparently with me she ate a lot of lettuce.

I looked down at my salad. I sighed. I was doing a lot of sighing today.

“Robert, what’s—?”

She suddenly stood up, knocking her bottle of water to the floor. She was waving her hand at someone by the coffee bar, just in front of the escalators.

“Maria!” mum called out.

I looked over to where mum was waving and I saw Maria. Her head just about reached the counter, that’s how short she was.

“Maria,” mum called again.

Maria turned away from the escalators she’d just come up from, but she just stood there. Frozen. Something was wrong. Then two policemen rushed in. One of them grabbed hold of Maria’s arm and then— someone was shouting from below the escalators—“C'est elle! C'est elle! Au voleur! Au voleur!”

The restaurant had gone very quiet. All the noise had stopped. There were no more trays banging, chairs scraping, or dishes crashing on the floor, or knives and forks tinkling or people talking... we were all waiting to see what would happen next. We were all holding our breath like we were in a movie.

I—we watched the stairs coming up and it was—

This mega giant in a black suit, with bright red hair combed back, away from his face, and I guess he had some wax in it because it didn’t move even though he was shaking his head, left and right, while he jabbed at Maria with the Tribune de Geneve that was in his left hand, shouting,

“That’s her! That’s her! Thief! Thief!”

The policeman pushed the newspaper down and I guess he was telling the man to step back because he was holding out his arm. I held my breath. The man looked like he was really muscular under all those clothes. He wasn’t old. I guess he was roundabout dad’s age, and dad was forty-nine; if he wanted to he could just beat up the policeamn, and the other one. But he stepped back.

“Stay here,” said mum and then she went over to Maria and the policemen.

The giant was standing there, his right hand stuffed in his trouser pocket, his left hand still wagging at Maria with the Tribune de Geneve. He looked off balance, like if he wasn’t carful he was going to topple backwards, down the escalator.

And then he saw mum, and he stared at her for a bit, opened his mouth as if he was about to snap something, but then he swiveled round; he almost fell down the escalators that were going up; he looked around a bit like he was confused, then he walked round the tables, his right hand still in his pocket like he was holding something down in there and he came right by my table, bumped against it, and even then he didn’t take out his right hand from his pocket to rub his knee, he just slapped the table with the Tribune de Geneve, looked at me, his thick red eyebrows which looked like he’d put wax on them too because they looked so shiny wrinkling like caterpillars, and went round to the other escalators, going down.

“Monsieur!” the policeman called, after him. “Monsieur, arrêtez-vous, s’il vous plait!”

But Monsieur had already disappeared down the stairs.

One of the policemen went running after him.

Mum was standing next to the policeman, her hand on Maria’s shoulder. The policeman turned round and looked down at mum. He didn’t look too happy. What if he arrested her? He said some things to mum and then he turned back to Maria, one hand on the handcuffs dangling from his belt. He towered over Maria because she was really short, shorter than mum, shorter than me and I’m one metre fifty-two centemetres tall.

Mum had got to know Maria really well because when I was a baby, zillions of years ago, mum had spent a lot of time in the park downstairs and Maria had spent a lot of time down there too, looking after the neighbour’s kid. She worked for the family who lived in the apartment upstairs ours. She slept in their kitchen. She wasn’t just a maid. She was a cook, baby-minder, housecleaner. She didn’t have any days off even though it was illegal and she was paid very little. She couldn’t go and complain because she was only in the country on the neighbour’s family diplomatic visa. If she complained they would throw her out of Switzerland and she would have to go back to Bolivia and then her child wouldn’t have enough money to go to school or university. Dad said that she was being exploited

Even though she was younger than mum, Maria had lots of white hair in her bushy ponytail.

If you worry too much your hair gets grey and white, like what happened to Marie Antoinette who was the Queen of France; she got all worried about losing her head on the guillotine that her hair turned white overnight; mum thinks that’s an urban legend but Horrible Histories says it’s true; or if you stress out too much you can just lose your hair and become bald, like what happened to dad when he was like nineteen and some girlfriend zoned him (not mum).

The policeman was pushing Maria along with his hand. They passed my table. Maria didn’t see me. She was looking straight ahead. She was crying softly. Mum was behind them. The policeman and Maria went down the escalators. Mum came back to the table and sat down. She shook her head like she couldn’t believe what had just happened, like it really was a movie.

“Mum, what happened?”

She looked very tired; we’d done quite a lot of stuff today. My baby sister moved around a lot in her stomach and, apparently, she ate quite a lot too.

George: Great. Two FAT people in the family.

“Is Maria going to jail?”

That was kinda dumb of me to ask. Obviously she was going to jail. She was in handcuffs. Where else could she be going.

“I think there’s been some misunderstanding.”

“Did she steal something?” And then I felt really bad for saying that.

Mum shook her head.

“Remember the lady we saw her with in Coppet, the one she was looking after?”

I nodded.

“Well, the lady died, and that’s causing a lot of problems for Maria.”

The Woman in White, that’s what mum had called her.

Chapter Two: The Woman in White

Just after school broke up for the summer holidays, mum and I went to see Madame de Staël’s château in Coppet because she was going to use it in her next book.

Around Coppet there are pastures and orchards and vineyards on the mountain slopes; we go there often in summer because of the beaches and the buvettes along the lake. In the olden days, Coppet had the only road to get in and out of Switzerland, la Grand Rue, which had a gate and you had to pay if you wanted to go to Lausanne or all the way to Austria or Germany or Italy (if you went down) or if you wanted to go the other way, round the lake, to France. Mum said in those days people walked a lot because cars hadn’t been invented yet. Jean-Jacques Rousseau used to walk all the way from Paris to Geneva. That’s hundreds and hundreds of kilometres. And he had to go over mountains. Ladies used to get carried around in special chairs, especially the fat ones. If you were rich you could go by carriage.

I liked walking on the Grand Rue, looking up and reading the fancy signs on iron boards hanging from the roofs: L’Ancienne Auberge des Quatre-Cantons, L’Hotel d’Orange, L’Auberge de la Croix Blanche, the hotels the pietons could stay in for a rest; mum said some regular houses became hotels or inns when there were too many travellers around. In the olden days there were only, like, a hundred people living in Coppet, most of it was just forest and fields and gardens, today there’s about three thousand people mostly because of the foreigners who live there but who work in Geneva. There was the Baron of Coppet who owned the castle and because the castle had been built hundreds of years ago there were quite a few barons, and all the people lower down who were the artisans and the people working in the castle and also some more wealthy people who lived on the Grand Rue where there are houses from the 16th century which mum says are gothic in architecture. I don’t think they look that spooky.

Madame de Staël used to live in the castle in the 18th century, and now she’s buried in the gardens there, her father too. Her father, who used to work for the King of France, owned the castle then and when he died it became hers, but she used to live more in France because of the culture. But during the French Revolution when they started chopping people’s heads off with the guillotine - I knew all about the French Revolution from Horrible Histories - in The Reign of Terror - she had to make a run for it to escape the angry, hungry people who couldn’t eat cake instead of bread, like the Queen haughtily told them to when they complained that there was no bread. A whole mob of people started rattling her carriage while she was in it and they took her to the commune which was where they decided who kept their heads and who didn’t. Luckily, she was a good talker and convinced them to let her go. And then she had to run away from Napoleon Bonaparte when he was in charge of France because he didn’t like her talking about the constitution and he thought women should be quiet and look pretty. He was definitely a sexist. I asked mum if Madame de Staël was a feminist. Mum said, yes, even though the word hadn’t been invented yet. She said there were quite a few women like that at the time, who spoke their minds and were creative.

“I really want to get a feel of the place,” said mum. “How it was to live there. I have this idea brewing about a romantic thriller set in Coppet, juxtaposing the present day with the nineteenth century, two, maybe even three parallel narratives intersecting at some points, a kind of time travel...”

Ugh. Romantic Thriller. Mum had tried to write a book about vampires but in the end she had to kill them all because she couldn’t give them any life. Maybe the same would happen with this idea.

Madame de Staël wrote books and she used to hold salons and soirées where lots of writers and intellectuals spent the whole time eating, talking about art, and gossiping too. Mum liked to read diaries from those days. Lord Byron, Shelley, and Mary Shelley lived on the other side of the lake, in Cologny. Lord Byron wrote The Prisoner of Chillon - Château Chillon is a castle on the lake near Montreaux and, in the olden days, prisoners were kept in its cold, wet dungeons; The Prisoner of Chillon, is a poem about a real prisoner who was left there for many years. Mary Shelley wrote Fankenstein which mum and I had started listening to in the car. All three of them used to come from Cologny by boat to visit Madame de Staël, they just sailed themselves over; it seemed pretty far to go there on a little boat with no engine but, apparently, they did it lots of times. The olden day Swiss people thought that they, Lord Byron and the other English people, were mad, because in those days Swiss people never went swimming or sailing on the lake; they thought it had lots of diseases. Another thing that made Swiss people think that English people were crazy was that they went up to the mountains for fun; in the olden days Swiss people thought that there were monsters and dragons lurking up there in the mist; I mean, it’s English people who taught the Swiss how to use their mountains for skiing!

A fact: The Doctor in Doctor Who can only exist in England because he’s eccentric.

The château was pink. Seriously, couldn’t Madame de Staël have more style. It didn’t really look like a castle; there weren’t any turrets or towers; it looked more like a mansion or a palace. There was a whole room, the salon, which was pink: the walls, the floors, even the furniture! It was funny to think of the men sitting on the dainty chairs chit-chatting but when I saw the pictures of the men in those days with their garters and stockings and high healed shoes and their wigs and powdered faces I could kinda imagine it. Monsieur Brisquet showed us around; it was just mum and me and once he found out that mum was a writer (une écrivaine! une écrivaine!) he got really excited and and showed her the rooms that weren’t open to the public. After a while I got bored of looking at all the salons so I went outside and walked about in the field opposite which was bright yellow because of the mimosa growing there.

Just about the whole of Coppet used to belong to the château.

When mum was done we crossed the road and went to the buvette by the lake for something to drink, and an ice cream for me. There was a long pier and there were people waiting at the end of it for the steam-boat ferry from Geneva or Nyon to pick them up. Further away in the water there were some small sailing boats and catamarans from the école de voile.

“So,’ mum said. “All this part here, in Madame de Staël’s time, used to be just a muddy harbour the fishermen used.”

She wrote something down in her notebook.

“Lord Byron and his friends would have alighted here, in the mud, probably wearing wellington boots. They really must have looked so eccentric in their formal clothes, crossing the Grande Rue, and trudging up to the château, instead of coming up like or the other normal people on foot or, as well-born people, by carriage.”

A dog started yapping. Mum and I both turned.

“Oh, goodness,” said mum. “It’s Maria. I haven’r seen her in such a long time. I thought she might have gone back to Bolivia.”

Maria was walking with this lady and a dog. The dog was pretty small and he kept yapping. I’m always interested in dogs because I’ve been trying to convince mum to get me one for ages. Maria was holding the lady’s hand. She was saying to the lady, “Your name is — (I didn’t hear that part because the dog started yapping; he was pulling madly at his leash that Maria was holding). You are a wonderful person. You live, over there (Maria turned round and pointed); you are fifty-one years old.”

That was weird. Why was she telling the woman all this? Didn’t the woman know already who she was? Then Maria saw mum, and waved. She came over with the woman.

The woman had long, flowing golden hair, and someone had plaited daisies in it like a crown.

She had blue, blue eyes, the bluest eyes I’d ever seen.

She didn’t have any wrinkles. I mean mum didn’t have any wrinkles either but, I don’t know, it was like looking at one of those plastic pink dolls.

She was dressed all in white from top to bottom .

She looked like a Disney princess. But wearing white trousers instead of a gown.

The dog yapped. He broke free from his leash and he ran right over to me. He jumped on my lap. He licked my face, over and over.

Maria guided the lady to a chair. It took a long time for the lady to sit down. Maria took out a notebook and a pencil from her bag. She put it on the table, in front of the lady.

While mum and Maria were chatting I took the dog for a walk. He was really small. He seemed to like me a lot. I’m a dog person.

Later, mum said it was really sad about the woman, one moment she was bright and lively and then she would suddenly look so lost and confused like she was trying really hard to remember something, to stop herself from panicking and then she would bend over the notepad; she would make one squiggle then Maria would flip the page and the lady would squiggle something there, sometimes she would look at the pencil in her hand like she didn’t know what it was or what it was doing between her fingers and Maria would hold her hand and help her, all the time talking to her gently. Maria took out a mirror from her bag and put it on the table. Every now and then the lady would pick it up and look at her face in the mirror, and then she would put her finger on the glass as if she was trying to touch her face, or remember it with her finger.

The lady had Alzheimer's which usually happened to very old people. Alzheimer's meant you started losing your memory, you couldn’t remember your husband, or your children, your own name, and you even lost the memory of walking or eating.

But now she was dead.

Mum was talking to dad on her phone. She was telling him what had just happened.

Maybe the lady had forgotten how to breathe.

But that wasn’t Maria’s fault.

And why was she a voleur; she hadn’t stolen the woman’s memory.

When we saw Maria in Coppet she was so kind to the woman; she was trying to help the woman find her memory by telling her who she was.

Why was that man chasing her, accusing her? She didn’t have any bags? The policeman didn’t search her for anything. Why was he so mad?

Who was he?

“Dad’s going to look into it,” said mum when she was was finished.

Chapter Three: Facebook

When we got home, George gave the backpack a thumbs up. He said it looked too clean though. He said I should take it down to the park and kick it about in the grass. Yeah, thanks, bro, I’ll just make sure it rolls in some poo too.

It was weird that George was Swiss now. He had a Swiss passport. He still couldn’t vote in referendums even if he wanted to because he wasn’t old enough, but one day he could. And he would have to go the Swiss army when he finished school. But that wasn’t in his plans. He was going to be playing for Manchester United by then. Or, if they really begged him, Barcelona, even though he hated their tiki-taka....but now that Neymar was there, maybe they wouldn’t be so annoying.

I checked my e-mail. I actually had a message.

It was from Jin. I hadn’t seen him for the whole summer; he was still in Korea. South Korea. In North Korea everything is the exact opposite of South Korea. Nothing good happens in North Korea. In South Korea, Gangham Style happened and all other kinds of cool stuff, Jin is always showing me all kinds of pens and mangas he gets from there.

I opened the email.

It was the worst news ever.

Jin was on FACEBOOK and he already had one hundred friends. He wanted me to be a Facebook friend. I wasn’t even on Facebook. I didn’t even want to be on Facebook. What was the point? George said that if I didn’t go on Facebook I was going to be a major loser - I would have no friends. Not even real ones because everybody at school would be organising hang-outs on Facebook and I would be clueless and dope people hung-out on Facebook, exchanging Youtube videos and jokes and all kinds of other stuff. They’d be talking about things during school and I would be clueless.

I wasn’t old enough to be on Facebook. Jin wasn’t either. George just patted me on my shoulder. Loser, he whispered.

Jin had changed. He was going to have friends I didn’t know anything about. He was going to hang out and do stuff I didn’t know about. He was going to find out about things like the Harlem Shake Dance way before I knew anything about it, when I was still thinking Gangham style was cool. I could join Facebook. I could take the risk and become a criminal.

But I had seen what Facebook did. My brother, George, last year’s version. Back then, he was ruled by Facebook. He couldn’t even change his hairstyle without the thumbs up from Facebook. He was more into instagramming and snapchatting now - for example, he would sneak up on me and take pictures of me doing something random like sleeping and he’d doctor it with drool and then send it to his friends by phone. Ha ha ha. Apparently, it stayed there for like ten seconds and then got automatically deleted. I got really upset a couple of times and then I just ignored him, like mum said. It’s a fad. He’ll grow out of it. That’s being mature.

I looked at the screen. I didn’t know what to write. Then I just wrote about what had happened in Manor. And then when I’d finished and read it over and I was just about to press send I wrote: DON’T PASTE THIS ON YOUR WALL. I shouted it out to him. Virtually. I would have to be very careful from now on what I wrote to Jin. Thinking this made me kinda sad. Did it mean I couldn’t tell him any secrets? What kind of a best friend was that? I guess there was going to be lots of stuff to figure out this year. Maybe that’s why they called it Middle School. It was the working things out bit of growing up. I guess by the time you reached high school you’d figured things out although, sometimes, when I saw all those high school kids hanging about the stairs and the foyer at school, smooching, I hoped that there was more to it than that. Otherwise gross, just gross.

I kept thinking about Maria.

And I guess the reason I kept thinking about her was that she’d saved my life and, even though I was four at the time, I’m pretty sure I have a memory of it and that it’s not just because I’ve heard this story more than once from mum and she always tears up when she’s telling it, like she’s thinking about what could have happened if Maria hadn’t been there. How, I guess, I could just be a memory.

This is what happened.

There is a little hill in the park outside our building which has bushes. During the summer kids like going in there and making camps or just playing some kind of battle game or hide and seek; but lately, I heard mum complaining to dad, teenagers are hanging in there to smoke marijuana.

I’d dragged my tricycle up there and I was just about to pedal down the hill at full speed - because apparently I did most things at full speed back in those days before I knew the value of procrastination - and I was probably going to topple over and bash my head against the wall which was full of graffiti because teenagers liked hanging about there but, right at that moment, when I was all ready to go, my feet on the pedals, my body leaning against the bars - oh and I don’t think I was even wearing a helmet - this hand came out from behind the bushes and yanked me back from the brink. It was Maria. She’d been in the bushes chasing after her kid, I mean her boss’s kid. And mum hadn’t even seen me going up. She’d been on her phone. It was her agent. He was telling her that her first book was going to be published. So, she was in the middle of her phone conversation when she looked up and saw me perched on the hill and she screamed and the agent thought that she was screaming because she was so happy and excited.

So it was a pretty historic day, all in all.

A near death experience and a book deal.

When I looked outside now, the bushes seemed so innocent.

I had a history with them.

Another reason I was never leaving Geneva.

George said that was another one of my problems. I got way too attached to things. Mum said I was just very sentimental.

George: No, he’s a hoarder.

I shivered. Uh-uh. No ways. We’d watched this programme about these people whose houses were filled with stuff; they couldn’t move because of all the rubbish - I mean they didn’t think it was rubbish, that’s why they kept it - they had it filling up every space.

George: You’re going to end up like them

They were all depressed and lonely because no one wanted to marry them because they couldn’t even get in the house - they were in the programme because somebody was going to help them to de-hoard.

George: If you don’t get a grip.

We couldn’t use our lock up garage because it was full of things I wouldn’t let mum and dad throw away - like out old T.V, our old washing machine, our old stove...

They were part of our history.

Dad said I’d inherited a dose of both Nonna and Grandpa’s genes. They kept a lot of things because, you never know when they might be useful again.

I knew that mum and dad were going to do all they could to help Maria.

Mum wasn’t going to let her stay in jail.

At least it wasn’t a Zimbabwean jail.

My aunt Delphia was put in one, last year. She wasn’t a criminal though. She was just trying to protect the game parks in Zimbabwe from poachers but the people doing some of the poaching were in the government and they didn’t like what Aunty Delphia had to say. So they put her in prison to shut her up, but then they let her go because they hadn’t really shut her up by putting her in jail. She was in the news and she won an award. It was embarrassing for the government. They hurt her in there, but she got better in Geneva. And now she’s in New Zealand with my cousin, Cynthia, where she’s looking after a lot of sheep; she’s a veterinarian and, in Zimbabwe, she looked after wild animals.

Dad had found out that Maria was in the police station in Servette which was five tram stops away. The police were checking her papers. They could keep her in jail as long as they wanted. Maria needed a lawyer.

Mum was making phone calls.

I left mum in the lounge. I sat down with my computer in the hangout room. I thought about googling Maria. But I didn’t even know her surname. I started typing Maria Bolivian mai–, but that just felt so wrong. I deleted it.

Maria was my saviour.

Without her there would be no me today.