I wrote my debut novel, The Boy Next Door, in Geneva, in a beautiful rush of inspiration, over a nine-month period. I cannot remember the exact day I set down those first three lines - Two days after I turned fourteen the son of our neighbor set his step mother alight - lines which have remained the same over countless drafts, but it came some time after a phone call from my family in Bulawayo during which they told me that there had been a fire in the house next door. My family had moved into the former designated whites’ only neighborhood at the cusp of Independence, and soon after our white neighbors began to move out, one after the other, except for our immediate neighbors on the right. I had never met the neighbors (I would glimpse their car going up and down our road, in and out of their gate, snatches of voices carrying over the walls) and their anonymity, decades later, opened up a whole fictional landscape for me, my imagination soared. The fire gave the story its beginning, its anchor. Its embers kindled a new flame, the terrain of the universe of The Boy Next Door. And its ashes spoke not only of the tragedy of that night but also of the buried crimes of war which link Ian and Lindiwe’s fathers in an unfolding mystery that reverberates throughout the novel.

I wrote in our apartment and while I waited for my sons during school pickups, at football grounds (in the buvettes when it was too cold) during training and sometimes during matches, in the park as the boys played; in cafés (just like Simone de Beauvoir and Sartre!), most often at my neighborhood Café du Soleil (my very own Café de Flore!), which is the oldest bistro in Geneva and has the best fondue (the guide books say so),

whenever and wherever, Lindiwe and Ian’s story gaining weight and substance even when I didn’t quite know where it would go, end. For when I write (that very first draft) there is never any plan to it, no mapping out of possible outcomes, trajectories, no drawing up of a character’s character. I am not that kind of writer. People ask me in readings, why does Ian do this? Why does Lindiwe act this way? I am at a loss. They just do! It is because they are Ian, Lindiwe. But you cannot say this; it sounds flippant, careless, dismissive. The reader wants to know, what was I, the author person, up to? Or they want to know how I created Ian. How did I get him so right? How is he a Rhodie, and not a caricature of one? How did I, in the new vocabulary I have just learnt, embody him?

If I had to make some kind of statement of what I think happens when I write I would say that my belief is that (my) fiction is autobiography translated (manifested) into art. My characters exist because of who I am; they are me – but not. I couldn’t write any other book than the one I’ve written; I cannot create any other characters than those that I do. They contain me – and multitudes. They are of me – and yet… reading back, this makes it sound as though I have a God complex (which is perhaps a requisite for being a writer?)!

About Ian:

The readers I met, and indeed the judges of the award I won, were convinced that Ian was real; he was so alive on the page he had to be someone I knew. And for some readers who had grown up in Rhodesia, through Ian’s lens (because they identified with him so strongly) they were finally able to see what damage their Rhodesia had done to their fellow citizens.

I grew up in Rhodesia and Zimbabwe surrounded by Rhodies. As a teenager I was part of a Christian youth group where, for a while, I was the only black member. At school, too, I was for years one of very few black students. But, what is a Rhodie? He is not just white. He is a culture. He is a language. He is mannerisms. A Rhodie is what should have been a historical artefact of the country that was Zimbabwe before independence, Rhodesia.

There were the Friday evening meetings at the church youth group which sometimes went long into the night as we went to the drive-in or to a Christian rock concert at the Trade Fair Hall, a reprieve for me from my parents’ rigid going out policy which was ‘no going out’. I had my first crushes there, Rhodie boys who rode motor-bikes - a picnic outing at Hillside dams and on the back of a bike, the boy asking me if I had ever been on a bike, no, I said, well, hop on, he said, and I did, my leg pressed unknowingly on the exhaust, a searing burn, I said nothing so thrilled was I to be behind a boy, this particular boy, with his sandy brown hair and his smell of old spice, my hands tight around his waist as we rattled along the dirt road, the scar still visible on my leg today; white boys who drove and drank Castle beers and joked about ‘chicks’, who was hot and who wasn’t, and what was ‘lekker’ and what wasn’t and who treated me like a kid sister - these were the safe white boys in the new Zimbabwe, Christians but not nerds, who still had the rough and tumble of outdoorsy life about them and who, my thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen year old self - who attended an all girls’ school, had no brothers - day-dreamed about, replacing the Hardy Boys, Dr Bill Barry…

I ask myself now, is this how and why I made Ian so sympathetic in The Boy Next Door? My vision clouded by the memory of my longings. If perhaps I saw those white boys through the filter of my extremely sheltered youth. Or perhaps those boys really were what they were to me back then, boys, too young to have fought in the war, to have been scarred and ruined by it?

In The Boy Next Door, Ian, after his release from jail, goes back to South Africa and returns to Zimbabwe a changed man because of his experiences there as a news photographer.

When I was sixteen, I won a prize at the church, for being a good Christian young woman I guess, and the prize was a trip to South Africa to a large Christian Youth Festival. I was desperate to go, and I don’t know how but my father allowed it. It was in the early eighties, and I was in a bus of young people, all white except for me, making the long drive to Pietermaritzburg in apartheid South Africa. It was the journey I had heard my school friends chat about - I’m going down South, Oh, I got this down South - and now, I was making that trip. The prize came with spending money and I already imagined all the sweets and fashionable clothes I would get. We had stopped at the main street of a small town, some of us were lounging on the green space when suddenly there was a whistle and sirens, followed by a wild scramble off the lawn; police vans had screeched to a halt, and out of them leapt policemen wielding batons, giving chase to people. I ran, leapt back into the bus and, watching from inside, I saw that the police were giving chase to only black people whilst the whites went on about their business. Inside the bus, no one talked about what was happening, and we continued our long journey, singing hymns and (clean) pop songs. At the conference, there were some other black faces, not very many. On the drive home, a week later, the thrill of sitting next to a boy, my age, his shoulder against mine, the tingle of it and, for a while, his head on my lap, asleep, and me looking down, daring myself to put my hand on his head, hair, my heart beating furiously.

Writing, I journeyed out out out of blissfully tranquil Geneva to my childhood, to Bulawayo in those fragile, fresh years after Independence, an independence that had been hard won after a long, bitter war.

The interplay of Ian and Lindiwe’s relationship over the 1980s and 1990s in Zimbabwe is the novel’s breathing heart. Lindiwe is coloured, but not a ‘real coloured’ as she says because she is not light-skinned and she has a wide nose. She is coloured because her father is. Ian, white. Lindiwe has just turned fourteen when they meet; Ian, seventeen.

Bulawayo- Bu-la wa-yo- the place of slaughter,

the city of kings and the city of skies, in the 1980s, is a vibrant character of its own in the novel. In their burgeoning relationship, Lindiwe and Ian meet in different locations throughout the city: the Railway museum, the National Gallery,

the Holiday Inn, the National History Museum.

On a recent visit back to Bulawayo I went to the Natural History Museum in the once glorious Centenary park, a setting for one of Ian and Lindiwe’s pivotal encounters - I had not been back there for many years.

As a child, I had spent many wonderful moments in this building with its myriad treasures to be found in its different Halls, from the terrifying life-size wild mammals (the elephant there is the second largest mounted elephant in the world, and perhaps in the 1980s was the largest) to the Hall of Man and Chiefs, where I would stand mesmerized at the display of an open notebook belonging to a colonizer whose pages had been pierced through by a bullet, the subconscious memory of which perhaps planted the seeds for the mystery surrounding the true nature of the relationship between Ian and Lindiwe’s fathers,

to the ephemeral, somewhat heart-breaking, displays of butterflies, their delicate wings pinned on kaylite boards.

I felt emotional as I followed a young Ian and teenage Lindiwe’s footsteps throughout the museum; I went down to the basement, ordered a plate of fried chicken and rice and a Stoney ginger beer, sat at one of tables where Ian and Lindiwe had sat drinking their cokes, their voices alive in my head.

I had been sending manuscripts to publishers: from Bogota in the early 1990s, Barbados in the mid 1990s, and Zimbabwe in the late 1990s, early 2000’s, and getting rejection slip after rejection slip. Sometimes, I came tantalizingly close to that promised land of ‘published writer’. A rejection letter from the editor of what used to be the Heinemann African Writer’s series came with a detailed Reader’s Note which stated that the manuscript was way above the standard of submissions for the series… the manuscript had passed through several rounds of the submission approval process only to fail at the final hurdle, marketability. Rediscovering the novel in my archives I have to admit that it is a rather kaleidoscopic mess of a journey that takes place largely in a mental asylum and I can quite understand how a reader might get tired of the ramblings of The Spiritual Advisor, The Mermaid, The Sniffer… it needed (needs) a very committed editor to whip it into shape.

And then, one unforgettable afternoon in July of 2008, I received the phone call from my agent (the journey to finally landing an agent is a tale in itself). They wanted to publish my book, and they was not just any old publisher but the esteemed American publisher, Little Brown. The editor he had submitted it to had felt an immediate connection to Ian, the young Rhodesian, Lindiwe’s love interest. She had spent her childhood in Rhodesia, but more than the politics of it all it was the characters that leapt out for her, she wrote to me.

It is hard to describe those wonderful, heady months - over a year, in fact, bringing a book to publication is a long process - leading up to publication: the excitement of the foreign deals (and ultimately the foreign editions with their own covers),

the rounds of editing, the proof reading - these were manually done, which meant my publisher sent me the drafts through UPS all the way to Geneva and me sending my corrections back the same way, typesetting, the first sight of the manuscript as how it would appear on the page as a book, the cover reveal, the advanced reading copies where there my words lay in book form to be distributed to reviewers, booksellers, readers, libraries to drum up interest and excitement, that ‘word of mouth’, fervor, my book in the publisher’s catalogue with the promise of a big publicity push (adverts in the esteemed New York Times!).

The excitement of the book trailers.

And then, there it was, the real book in my hands. I was, finally, a published writer, my debut sitting on shelves, in bookshops, in Barnes and Nobles, Waterstones, in bookshops in South Africa, Kenya, Sweden, Poland… a thrill, every time, when someone told me they had seen it here, there! My words were out in the world, a thrilling, frightening realization of the magnitude of it all.

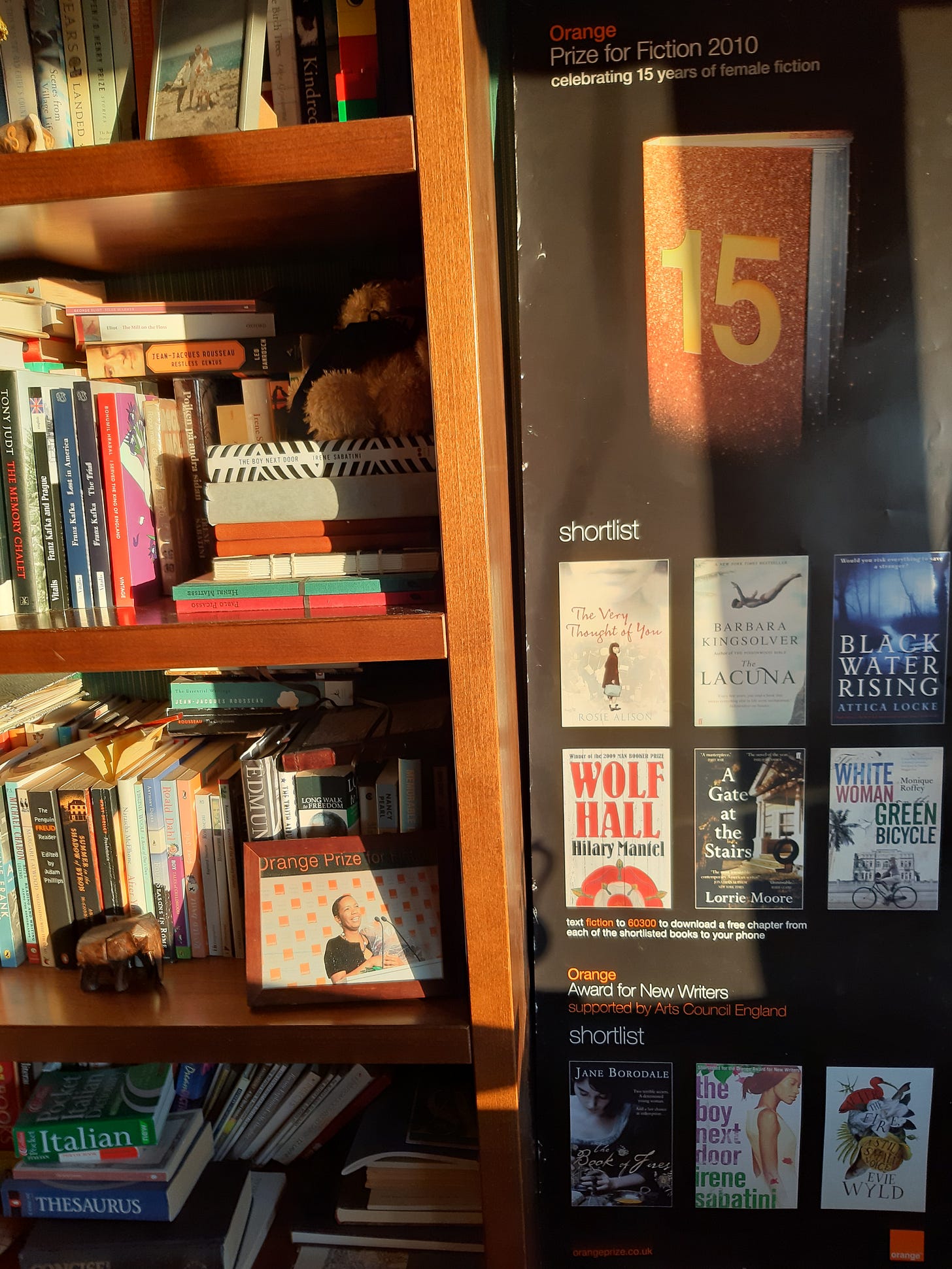

I won the Orange Award for New Writers in 2010, the year in which the contenders for the main prize included Barbara Kingsolver whom I spoke to; she said she was looking forward to reading my book, and Hilary Mantel, who I was too shy to approach.

The chair of judges, Di Spiers, gave a resounding endorsement of the novel, which had been unanimously chosen as the winner by the three judges …immediately engaging, vivid and buzzing with energy, The Boy Next Door is the work of a true storyteller... Irene Sabatini has written an important book that will enchant readers and which marks the emergence of a serious new talent…

And then I took to the stage, overwhelmed. I had not in a million years thought that I would win. I gave my speech as the Duchess of Cornwall sat behind me; I had met her moments earlier in the private reception on the balcony of the Clore ballroom of the Royal Festival Hall to celebrate the 15th anniversary of the prize. The PR person had whispered in my ear that I was to meet the Duchess, and thinking that this was an invitation that was being extended to the other two New Writers shortlisted authors I thought nothing of it. But no, it was just me with the main prize shortlisted authors sitting down with her, discussing books. I should have known then that I had won.

One of the three judges of the Award for New Writers later told me that I was brave in my story and characterization in The Boy Next Door. I pondered her words for a long time.

When I wrote The Boy Next Door I had no fear (of causing offense) because I was writing in my own bubble. I wasn’t afraid because I didn’t think I was writing anything outrageous or controversial. It was a story of a boy and a girl with their own issues growing up and living in a troubled country.

About Lindiwe: On Identity

It is true to say that teenage Lindiwe, has the sensitivity and insecurities of a teenage Irene coming of age in a country mired in racist ideology, and then recovering from a civil war.

I went to the Dominican Convent School the year I turned eight in colonial Rhodesia.

It was the only multiracial school in Bulawayo. Originally, I was supposed to be enrolled at Mckeurten (several blocks away from the Dominican convent) which was the government primary school for Coloureds in Rhodesia. Rhodesia had a three-tier educational system. Tier One: Europeans - they had the vast majority of the government’s educational budget; Tier 2: Asians and Coloureds and Tier 3: Africans, an afterthought. Mission schools in the rural areas filled in the gap when it came to quality education for ‘the Africans’.

At the McKeurten entrance interview, the headmistress made some comment on whether I was really eligible for Coloured status, given that my mother was black. My dad promptly got up and walked us to the other end of Lobengula street and pleaded my case so strongly that the nuns enrolled me; the school was a private one and so my parents had to make great sacrifices to send me there.

At school, I was, for a time, the Coloured girl who looked black. In my first five years at school, Zimbabwe was still Rhodesia, and the intake of black students was low at the Convent. After independence, in 1980, many white families packed up their bags and fled to South Africa, Australia and England. Black, Coloured and Asian students started filling the hallways; the character and conversations of the school changed. I was no longer alone, but I still felt an outsider. I could not converse at lunchtimes in Ndebele with the black students as I had lost it; at school I had had my ears twisted on the very first day when I spoke in Ndebele so that put an end to that, and in my parent’s determination that I excel in school they spoke to me in English at home. Oh, you speak so well, white readers of The Boy Next Door would tell me at book signings. What’s your first language? English, I would reply, confused, affronted by the question, but also, somehow shamed by my answer.

What made me coloured was my father being coloured. When the black girls came they took one look at me and laughed, you’re black. Come on, who are you fooling, look at your hair, your face, your complexion - my complexion could have passed, I was much lighter than a coloured schoolmate who was a dark as my mother, even darker, but she had good hair and a ‘white’ nose. They thought I didn’t speak Ndebele because I wanted so badly to be white. For the first time I considered I was black. Why had I chosen to believe I was coloured when my mom was black?

Every time I go back to Bulawayo, to my childhood home, I feel a great sense of loss at not being fluent in Ndebele, the language of Matabeleland. I long for it to be my mother tongue. When my aunts and cousins, and cousins’ cousins, come and they are all seated under my tree which has been there since we moved into the house, and they are having tea, gossiping, the lyricism and expressiveness of Ndebele, where insults sound spicier and juicier, brings a kind of heartache. I can only answer jocular queries in a broken-down proxy of the language, my tongue heavy in my mouth, unable to produce the click sounds in words like iqala (to begin) , kuyaqhanda (it is cold), iqanda (egg), qeda (finish), qoqoda (to knock) - which embarrasses and shames me. Umkhiwnana, they tease, The little white one, not out of malice, but amusement, even a kind of pride that I can speak English so well.

I lost Ndebele and I spoke English so well that when colleagues of my father phoned and I picked up the phone they would compliment him and say that they thought they had been speaking to a white person.

When I returned to Zimbabwe in the 1990s I worked at an employment agency as an agent. It was owned by a white woman who would never consider herself a Rhodie because she was educated and did not have that harsh accent. The agency had three filing drawers. Top drawer - Whites; Middle drawer - Coloured and Asian; Bottom drawer - Africans. It didn’t matter what the qualifications of the job seekers were, they were classified solely by race. The bottom drawer was overflowing with applicants. Very well qualified applicants. The top drawer was sparse and the applicants were almost certainly poorly educated, high school not completed. A white applicant must have fallen on really hard times to seek work through the agency - the old boy network usually took care of their own. Sometimes, a company boss would phone the offices. I would pick up. They would tell me what their needs were, and then thinking they were being subtle they would finally add, ‘he or she must be blue-eyed.’ They would never have gone that far if they thought the person on the other end was black, but supposing I was a version of one of their own, they would feel free. I would pull out that first drawer and send the first file over to them. The only required qualification, after all, was ‘blue eyes’. I lasted just two months there.

At university, reading Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks, was psychological shattering, piercing deep into the neurosis affected by my school years… a normal Negro child, having grown up in a normal Negro family, will become abnormal on the slightest contact of the white world. This was completely radical to me, but how true; until I started school, I did not think there was anything wrong with me, that I was abnormal. I had spent my days running around the dirt streets and hiding out in the gullies of Magwegwe township with the other children who looked like me. And then, I was no longer the norm, the only black/coloured girl in the classroom. I began to understand why I felt like I did. Discovering Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison, Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, was seeing into and through my own oppression and self-hate, my fraught desire to be other. The tentacles of racist ideology strike very deeply into the psyche and I believe it is a life-long work to get rid of its hold on you, to save yourself, and still I fear that some of that damage done in those early years is irrevocable, so deep-rooted it has meshed with whatever the soul may be, become who I am.

Perhaps the Lindiwes, the Gabrielles of my fictions are a way of fleshing out the identity issues that stem from that early childhood trauma of dislocation and displacement.

I wonder who I would be, the version of myself, if in the country called Rhodesia I had gone to an African school in the townships. What it would mean to have Ndebele as my mother tongue, to be seeped deep in the culture of the Ndebele people, to have that as a complete part of my being. What stories would I tell in my fictions then? What voices would arise?