I lived in Barbados for three years in the mid 1990s. Fabio and I came from Colombia to this island paradise; after those four high-octane years, here we were in ‘Little England’ with its white sandy beaches and calm. The contrast between the two countries was like night and day.

In Barbados I learnt how to ride a motorbike - the very first time I got on it I rode right into the kitchen door because Fabio told me to ‘just rev it’ and forgot to tell me how to brake. I spent days traversing the island, north to south, east to west, going along main roads and dirt tracks, through sugar cane fields, the cane rising above me on either side for miles on end until in a rush, I was out of it, the silence, into the open road. I rode up the hills along the East Coast, and once got so lost and disorientated (it is hard to get lost in Barbados as the island is rather small and you need only look for the Bus Stop Signs which say simply ‘To City’, and ‘Out of City’ to find your bearings).

I passed the massive rubbish heaps the crows alighted on them and the pig farms of the back country, the smell so overwhelming I threw up. I rode to the beaches with my backpack, parked my bike against a tree, a rock and went off to swim. I was a novelty back them, the girl on the motorbike whizzing about the island.

I rode my bike to the schools where I was doing research work for an international aid organization through the different Parishes, up to the city, Bridgetown and along the South Coast through the narrow, patchy streets off the main thoroughfare, Bay Street, where chattel houses were crammed up against each other and where the sweet children in their blue uniforms reminded me so much of my township years in Magwegwe as a child, to the school on the western side of the island up on a hill, in the country, whose fathers or grandfathers were fishermen whom I would pass mending their nets by their humble boats on the beach, and where the upstairs wooden balcony had a floor so weathered down it was liable to collapse at any moment.

I was asked to write a paper about corporal punishment by a children’s organization who was lobbying the government to prohibit it; there was little debate then in Barbados about this as it was (and is) legal - I was often assailed with spare the rod, spare the child. I argued (rather emotively, more novelist than the measured scientist that my MSc. in Child Development proclaimed me to be) -

Fabio’s sister and his nephew and niece came to visit. I took the children round to the schools where I worked, and I remember how wide-eyed they were, how this was their first experience of being a minority, to be ‘out of place’ (but warmly welcomed), I was till then the only black person they knew, how it felt, watching them, the world was being made new in their eyes. Nonna was with us on another visit and in one of my favorite pictures of her she is in our garden posing and smiling girlishly, a pink hibiscus flower tucked behind her ear.

Almost two decades later, Fabio and I returned to Barbados, a family of four now. We had brought the boys to the island, to our youth. We could not find the house where we had lived in in the St James Parish. In our last year in Barbados there had been a surge in construction in the area, but still it was shocking how much had changed. We drove up and down the streets, but we could not find the house. How possible was it to be so disorientated in a place we had lived in for three years. Perhaps it had been knocked down, replaced with something grander?

We loved taking the boys to our old haunts, Harrison’s Cave with its stalagmites and stalactites, the fish market at Oistins, Earthworks Pottery and studio with its lovely jewel-like and marine-colored pieces which, when I look at them now, always sweep me back to the island,

Animal Flower Cave in the most northerly point of Barbados to see the sea anemones in the pools of the caves - it was a quite a moment for me when I saw sea anemones for the first time because I remembered reading as a child in landlocked Bulawayo about them in a novel and being fascinated by these brightly colored plants which were really animals which killed their prey with their tentacles and poisons. With the boys we stood on the rugged cliffs (like we had done with Nonna decades before) and watched the mighty waves crash on the rocks. In the winter months Fabio and I had watched humpback whales and their their calves playing in the water, out in the ocean.

And, of course, the various beaches:

Accra Beach on the South Coast, where I once got caught in a rip current I thought I would die, swirls of sand and water suffocating me, until the sea coughed me out on the beach, to the almost deserted Bottom’s Bay, white white sand and palm trees, gently rolling waves and no-one but us and the Rastafarian selling coconuts; Bottoms Bay - how the name made my youngest son laugh with glee, the boys and a friend running giddily on the humps of the bottom; the windy, rough waters of the East Coast, Bathsheba, where we would sit in the rock pools and be surprised by eels flitting in and out, where there was our beloved Bonito Bar to have their delicious flying fish sandwiches (how the boys squealed when they actually saw fish flying out of the water one day); to the incredible pink sand, Crane Beach, with its windswept palm trees and the rickety, wooden staircase, precariously winding down the cliff face, that led from the cliff all the way down (in later years when we came back there was an elevator to serve the new time-share resort which completely changed the character of this gem - Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous rated it as "one of the ten best beaches in the world"), the sand so fine and glittering pink (over subsequent visits algae would take over the beach and umbrellas, umbrellas everywhere), and the forest of palm trees where some scenes from Pirates of the Caribbean were supposedly shot.

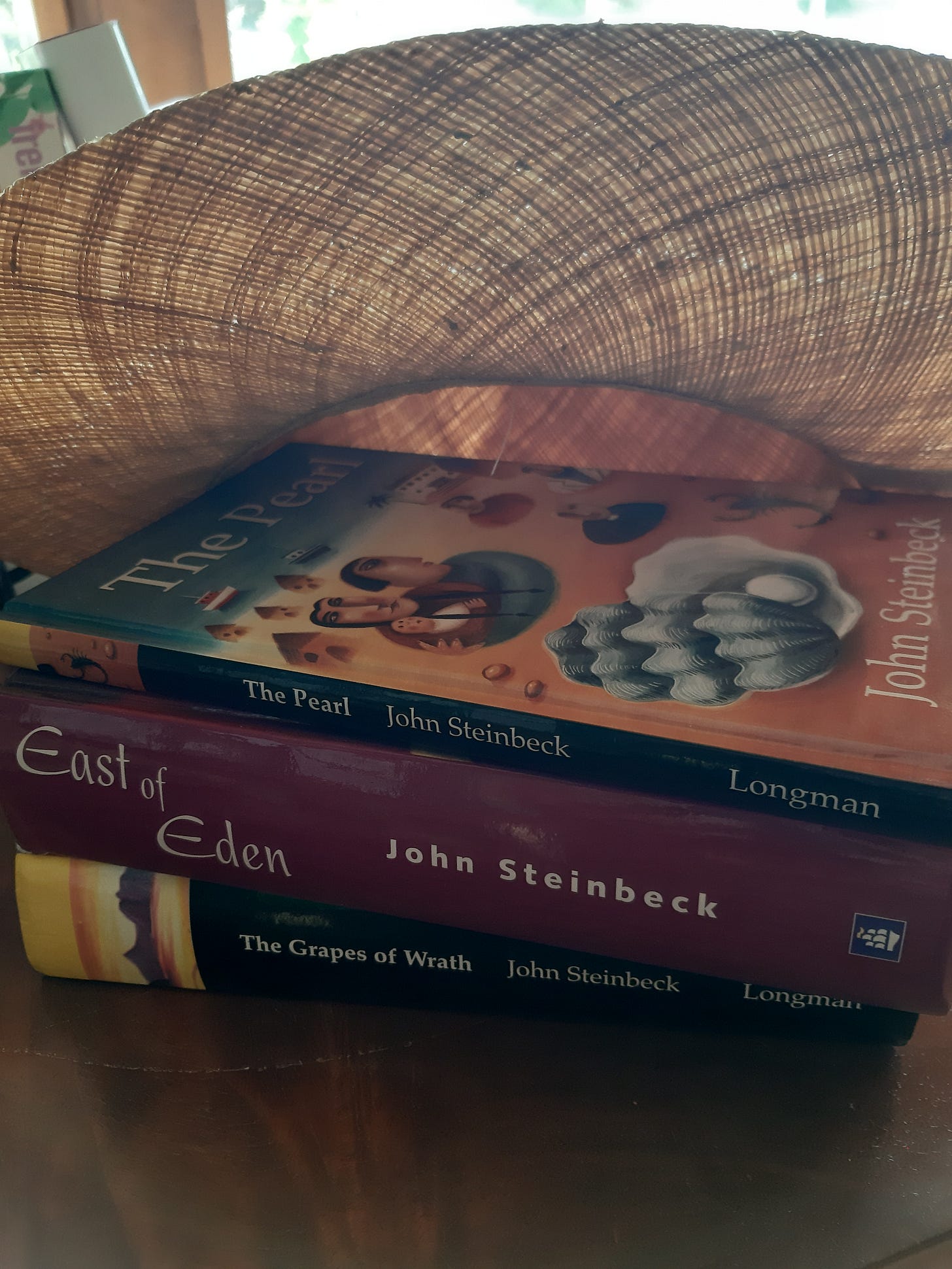

The waves at Crane beach were excellent for boogie boarding and the boys spent hours in the water with Fabio, while I read - one summer it was all Steinbeck - The Grapes of Wrath, East of Eden moving me to tears and so featured in The Lifesavers, (2008, unpublished) and decades later to be in Salinas at the Steinbeck Center, driving through his country, his hometown, seeing where and how the stories came from - my sons still talk about how I traumatized them by putting The Pearl audio book on our drives back and forth to their school in Geneva - I had no idea how tragic the story was - but my boys remember it well!

Sometimes, I braved the water and I rode the waves too,

and afterwards there was English tea in the restaurant up on the cliff, sustenance and reward for our exhausted selves.

Once we got caught in a ferocious summer storm on Crane beach with the boys and some friends. We stood on the beach, the tide rising at an alarming rate, eroding the sand under our feet, within minutes we might end up washed up in the sea. We stood there not knowing what to do: to run up to the stairs and go up to the restaurant where we could barely make out people standing against the panes of glass watching us, or to go back to our car which was parked in the public entrance to the beach which meant that we would have to navigate the boulders which were hazardous enough when it was dry, but now, the waves were lashing at them, the boulders more slippery then ever. Fabio was all for waiting it out; he was certain the storm would cease at any moment. In my fear I think I might have started to cry. We hazarded the boulders, and just as we stepped into the car, the clouds cleared, and the sun shone through again. I had no regrets: the sea has no back door, a Bajan saying, had gripped me on beach, that day.

The boys loved Mullins beach; this was our neighborhood beach when Fabio and I lived in Barbados: during the week I would zip down there on my bike, five minutes and I would be in the water. During weekends, Fabio and I would bring our dog, Max, there and spend hours just chilling under a palm tree.

There was the beach bar for refreshments.

One season, a hurricane (Marilyn) came as close to the island as it has ever done in years (Barbados is the most easterly of the Caribbean islands and usually comes out of hurricane season unscathed), I remember the long night of the rain battering against the roof and the howling of the wind, in the morning the damage of fallen trees and the shock when we drove down to Mullins to find a large chunk of it gone, swept away by the water; decades later, most of the beach had been reclaimed again, but the tranquil, nearly always empty beach we had known was no more. The water was filled with jet skis going dangerously close to the buoys that marked off the swimming area and banana boats and a jumping castles and the sand was full of umbrellas. There was hardly a space to simply put a towel in the sand and sit under a palm tree like we had done so many years before. But still, it was beautiful.

Another beach, Paynes Bay, which the boys loved because of the platform, to which we returned to every day roundabout three o’clock when the sun was no longer so fierce. Fabio and the boys would swim to it while I watched from ashore, reading a book. Sometimes there would be ‘the stockbroker’ who, years before COVID, was already working from home, on the beach, trading stocks for his clients across the globe on his laptop - who knows how many millions were lost/gained as he sat there on the sand, casually sipping a beer. I am a nervous swimmer; I become anxious if I can no longer feel the sea bed under my feet, so the swim to the platform was a ‘no’ for me; I once reached half way to it, with the boys and their father, screaming and yelling encouragement from the platform, but a moment of panic, my feet treading the water and - what about sharks! - and I frantically made my way back to shore. One afternoon, as they larked around on the platform I was walking along the beach when I passed a young woman. It was Rihanna. I looked over to the platform and thought how bummed out my eldest son would be when I told him that I had actually been a meter or so from the Rihanna, whose umbrella umbrella ella ella was still all over the airwaves.

The platform and my boys’ summers on it became the inspiration and setting for The Lifesavers, a novel that sprang up after my follow up to A Boy Next Door had been rejected by my publishers (this was later published in 2020 by Indigo Press, reworked but the core story the same, as An Act of Defiance, ). It seems somehow fitting that I received the rejection of my follow-up novel from my agent while on holiday in Barbados, when we were still just celebrating the eminent publication of my debut novel. I started to write The Lifesavers on that same holiday, in the villa, on the beach, for I find that after a rejection my antidote to falling into despair and paralysis is to just quickly move on, and moving on for me means writing, writing, writing.

Coda: Extract from The Lifesavers (2008, unpublished)

1.

All aboard!”

It was always Jack Simpson who got there first, the one who called to them, standing on the platform in his orange board shorts, the rakish blue-and-yellow flag he used as a bandanna knotted at the back of his head, his deep-black eyes set against the finely arched eyebrows as though they had been expertly drawn on his skin by a kohl pencil, neatly filled in, and the lavish curtain of lashes, his thick hair so grown it fell to his shoulders. His fastest time clocked at one minute and fifty-two seconds, eighty-seven strokes; he’d etched the numbers on the boards with the Swiss knife that he sometimes swam with. The knife was in a Guatemalan cloth pouch tied around his waist with the belt made from nuts and berries from the rainforest, pilfered from his Colombian mother’s store of exotic clothing. His twin brother, Julian, would be next, his hands slapping the boards, moments after Jack’s. Then Chris who’d slowed down her strokes, keeping an eye on her brother Richard who’d struggle to lift himself out, his mouth so full of water that sometimes he retched and retched, worrying Chris about how much of the morning’s diet of pills remained in his body.

It was their platform, theirs alone: set across rows of empty plastic drums and anchored to the sea bed, lying out there, gently swaying in the water, calmly awaiting their daily onslaught.

The summer season had just begun and the tourists hadn’t flooded the island yet. The O’Learys were guests of the Simpsons (Mr. Simpson was a pharmaceutical executive) who had rented a coral stone, luxury villa up in the hills of the St James Parish which glittered pink and silver in the sun.

In the early mornings they’d careen down on their rented bikes. Six, seven o’clock, they’d be the only ones on the beach - the beach bar still closed - in the water.

They played football, basket ball, and even dodge ball. They shot hoops through imaginary nets. Their running, kicking, jumping feet rocked the wooden boards. They somersaulted in the water. Jack did the craziest stunts of them all, hurling his body into the air as though it were an elastic band that had been sprung loose.

They would pretend sometimes that they were on a raft and once they had argued about the plausibility of cutting the platform loose and seeing how far it would go with them on it. Richard had been all for it, trying to grab hold of the Swiss knife that Jack had put down, jumping up and down, shouting, “Zvakanaka, Zvakanaka, Zvakanaka” (the Shona word he’d picked up last Christmas in Zimbabwe), good, good, good, “let’s do it, let’s do it, yes, yes, yes, let’s-” the mania spilling over his voice, until Julian got hold of an arm and leg and swung him into the water, then panicked him by prizing his frantic, grasping fingers off the boards. Julian! She’d shouted, stop! But Julian was on his knees, slapping at Richard’s hands, his face. He’ll pass out, Julian! It was Jack who’d managed to push him away and who helped her heave Richard onto the platform.

When they were tired, but thirst and hunger not yet far enough, nor the sun quite high enough in the clear blue sky for it to be blazing at full strength on them, to get them screeching and howling in the water, to swimming back to shore, then up the hill, pedalling furiously, scrambling on their bikes on that narrow, twisting road that was flanked with sugar cane, for breakfast or lunch at the villa or the club restaurant, they lolled about the raft, as if they were lost far out at sea. If they turned their backs away from the beach with its palm trees whose long, slanting trunks arched over into the water they could be out there in the far reaches of the unknown, Robinson Crusoes.

If they closed their eyes as they lay sprawled, legs and hands atop one another, crisscrossing, their cheeks pressed against the warm boards, and were for a moment all quiet at the same time, the tide moving back and fro beneath them echoing their shallow breathing, the faint cry of some sea bird over them, they could be anywhere, castaways.

They simulated all possible scenarios, the dangers of storms and the languor of tranquil seas.

Who would, they asked themselves, survive amongst the four of them, and it was a question they answered by turning away from Jack and his limbs, the strength and grace of them making them feel like hapless children. They had seen what he could do on the waves in the East Coast, his body lithe and supple, dancing on the water.

“Right, hombres, who would we eat first?” Julian rubbed his hands, his eyes moving over each one of them as though checking for size and taste.

“No, no, no, who should we eat first - zvakanaka!” Richard, already excited by the idea of it all.

“Hombres, hombres, which delectable part of yourself would you dig into, and swallow?” Julian opened his mouth and made to take a chunk of his forearm.

“Arm! Thigh! Eyeball!” (Richard)

“Come on, seriously, how would that work?” Chris asked, rolling over to her side; she was disgusted by the thought and yet fascinated.

“I mean, logically speaking, if you eat parts of yourself you’re not really adding to any nutrients in your body, are you? Point One, you’re eating what’s already there. Point Two, you’re using up energy so you should actually get weaker.”

“Miss Smarty pants,” screamed Richard. “Smarty pants, smarty pants-”

“Shut up, Richard!” (Julian)

“Smarty pants.”

“Shut up, or you’re going overboard,” Julian, reaching for his ankles.

“It would be kind of like fooling the body,” Jack said, flicking the knife over his palm, “buying yourself time.”

“Yeah right, bro, not even the sharks would go near you after you’re done eating yourself up.”

“They’d have you for breakfast, munch, munch, munch-” and there was Richard again, jumping up and down and Julian tackling him, her brother yelping and crying until he slumped down on the boards and played dead, his legs and arms stiff and unmoving, drool frothing at his mouth, frightening Chris who splashed water over him and pressed her ear to his heart.

Sometimes, she felt, they drove each other to a kind of delicious sea sickness, feverish and delirious as if really they had been exposed in the seas for days.

There was Jack, his hand forming a peak over his eyes so he could look far off into the horizon, scanning it for land that was, had to be, somewhere there in all that forlorn space, the compass around his neck glinting in the sun, the shark tooth on the leather lanyard turned so that it fell over his back which had been burnt, then peeled, rubbed raw by sand and salt, and was now turning to a deeper bronze.

She would sit, her legs dipping in the water, the sun beating on her shoulders, imagining what it might really be like to find yourself alone, afloat in the open waters. Or she might be thinking of the book she had left on the beach. East of Eden, and Jack’s voice as he read to her. There were other thoughts that flitted through her, drawing her inwards, her hands hugging her knees - a touch, a whisper, a kiss - and then, afraid of the bliss that might betray her, which played on her lips, she would stare at the sea again, lie down, her cheek pressed against the wood, her fingers trailing the water, her reverie punctuated by a sudden cry or a splash as the others larked about.

But, that one time, Julian’s cry had splintered the air, ripping through their sea faring ways.

“Jack!”

She wasn’t looking, not at him in that instance of his jump but at the garish ‘banana boat’ that was being dragged, thumping and pounding, through the water with its shrieking, rum-filled bouncing tourists, their skinned legs straddling either end of the banana.

She turned to see the red, swirling in the water, and Julian frozen on the platform.

She jumped.

I jumped in the water and lifted his head, cradled it under my arm, she told Mark years later as she lay in a chalet in the hills around Château-d’Oex, her head resting on his chest, the clear sound of an alphorn carried over to them, an ache welling, pulling inside her.

She kept going back to that swim, the quiet of it, his head pressed against her chin. She had managed to carry him through, alone. She had saved his life, they all said. And yet. The feeling wouldn’t leave her. She could have done more. Reacted quicker. She could have seen exactly what had happened, how he had fallen. She could have warned him. She had seen him do those flips of his, come dangerously close to the buoys.

I swam to the shore. He lay on the sand. The water lapping at his feet, the tide coming, in and out, a crab scurrying away, are the things that I remember.

She swam with him, easily it seemed, as if she had been trained for it, as if she knew how by some instinct.

Breathe, I whispered to him. Breathe. And then I kissed him.

When they took her hand away, there was his blood on her palm.

She looked up out, over the water and saw Julian standing on the platform lit up by the sun. He lifted his body, dived gracefully into the water. And Richard, abandoned on the platform, his arms clenched around his body, howling into the still air.

She lifted her bloodied hand and, as she watched Julian swim to the shore, she pressed his brother’s blood on her hair, pressed hard on the beads.

She’d had her hair braided under a casurina tree on Accra Beach on the South Coast. Julian was in the water and Richard had stayed behind in the villa with a stomach ache. Jack was stretched out on the sand, his arms right behind his head, it looked painful. And then he’d turned over on his side, picked up her book - East of Eden - which she’d found in one of the villa’s bookcases. He flipped it to her marker, a piece of knotted string, and then he did something she found wonderful. He read, aloud. Chapter Eight. And sometimes, in her sleep. she still heard that voice at that particular moment, its timbre… I believe there are monsters born in the world to human parents. And they, she and the woman braiding, listened to him. He read sincerely, without irony or mockery. His voice was clear and grown. He read the entire chapter.

She finished the book days later and she judged it to be overwrought and exaggerated. But she loved it, all the same. She didn’t believe anyone like Cathy could possibly exist. Cathy was the devil. She didn’t believe in monsters, then.

As she watched him coming out of the water, walking in the sand, she pulled at the beads until one came off in her hand and she looked at it covered in blood. I’m holding bits of him, the thought skirted her. He’s here, in my hand.

“He’s okay,” she heard someone call out. “He’s breathing!”

She looked away from Julian to Jack. One of the bar waiters (she recognised him, the one who’d tried to get her to drink a rum punch with vodka in it) was pressing a napkin on the wound and the red was seeping through. There were people clambering down the steps. “Don’t move him,” she heard. “We’ve called the ambulance,” she heard again. “These kids are always by themselves,” she heard. “An accident just waiting to happen.” She sat down on the sand and looked at Jack. He was pale, shockingly pale, his hair, clinging to his forehead and his eyes were closed. She took his right hand, held it. She pressed her thumb on his wrist and felt the faint pulse of his life.