In a flea market in Rolle in the Swiss canton of Vaud, I fell in love with a painting, an unsettling image of a doll looking into a mirror. There is something off about the image, is it really a reflection or is that doll looking through the looking glass at herself but as she exists in another world, I keep looking and looking to see. The painting now rests against a low shelf in my study, a spooky presence when I look up and the doll’s rather tragic face catches me off-guard. I am sure a story lies there, somewhere; I will try any means to get to my fictions.

In the summer of 2019, taking a break from the college tour I was doing with R, and while he was using his down time to attend Dublin comic-con, I snuck off to see the work of Frances Bacon at the Dublin City Gallery, The Hugh Lane.

I did not expect to find his studio there. I had never seen anything like it: the 6 times 4 metre square space enclosed in glass was his actual studio, transported and re-installed in its entirety and exactness (over 7000 items) from 7 Reece Mews, South Kensington, in London. As the brochure stated: it …was the nerve centre of Bacon’s world. And what a nerve centre! There was not an inch of uncovered space, I could hardly imagine where Bacon could have stood in it, painting. Books, canvases, paper, magazines, paints, brushes, clothes, a boot….clutter clutter clutter. I found it completely inspiring, and in a way I find hard to explain, uplifting. There was something so profoundly human in that space, a true artist lived and breathed in it and created.

I had never seen Bacon’s work before, and walking through the gallery, his phantasmagorical figures unsettled and entranced me, and it seemed to me that they could only have come from that particular artist working in that particular studio.

An artist inhabits their own space, their own world, and it is true for me, in my small way.

Some time ago I read The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Arles by Martin Gayford. I picked it up from the National Gallery shop in London, just after I had seen Van Gogh’s sunflowers, and was so moved by them.

I loved the description of Gauguin going into the house that Van Gogh had rented in Provence and marvelling at the canvasses that Van Gogh had hung up on the walls; Van Gogh finishing a painting and then casually hanging it up seems to me such a simple and profound thing. He hung the first two of the sunflower canvases in Paul Gauguin’s room. And then when he needed to sell a work he would just pluck it off the wall and send it off to his dealer brother. The paintings existed on his wall as much as they existed on gallery walls. Commerce did not give them ‘value’ in the same way as it does a written work. A qualifier: Van Gogh did despair when he went to visit his brother in Paris and found his paintings stuffed in cupboards, under the bed, gathering dust, getting ruined; there were so man of them, Theo could not find buyers.

A book does not exist until it is published. One can bind a manuscript and put it on the shelf but it is not a book. For a book to exist it has to be vetted. For a painting to exist it has to be simply painted. Whether that painting is art is another matter.

What, then, is my body of work? Three published novels. The finished manuscripts in my hard drive count for nothing. Unseen, they do not exist, .

A writer who paints, that would be my dream. But if not a painter in my real life then I have embodied her in Mathilda, a frustrated artist in the chauvinistic world of white Rhodesia, who finally flees and finds success in London and New York. She exists not only in my head but on paper, in words, in the unpublished novel, The Rhodesians/The History Makers. Here she is at nineteen bursting with excitement:

…Besides, she was still taking in the news that had arrived in the morning post. She felt in the pocket of her dress, was tempted to take out the envelope but held herself in check. Now was not the time. What if her father came stumbling in and wanted to know what was in the letter. She had to pick an opportune moment to tell him. Her wonderful news. She had been accepted to art school. London. They thought her work was good enough. After months of working in secret by the stables and at school, sending her portfolio, the waiting, they had finally given her a verdict. There was a place for her at St Martin’s School of Art. She would leave provincial Rhodesia, Rusape, and be in London. The thought made her heart soar. She tried to imagine herself going into galleries in London, looking at art works by real artists, by the masters, not picture cards, posters, but the very real things, just there for her to see. Going into the National Art Gallery, looking, looking at all that art. It made her dizzy to think of it. But there was the matter of her father. How he would take the news. He had made allowances for her drawings, though he never asked to see anything she drew or painted and, if he considered art at all perhaps it was merely for decorative purposes, something you stuck on the wall because something must be stuck there. What her father did resent about her ‘dabbling’ was that she didn’t do all that dabbling outdoors. Why was she not a member of the Woman’s Institute and one of their art clubs - why wasn’t she outdoors painting flowers and birds, things that he could put up on his office walls, flora and fauna? Why did she lock herself up in the (former) stables and insist on painting there? What on earth could she see out there? Nothing. Nothing at all.

Mathilda lies there on paper, unseen. I may have to kill my darling, but not before she has taken a breath.

I chanced upon a restaurant in the old town in Geneva which had what I imagined was the feel of Van Gogh’s yellow house. When I climbed up the narrow, spiralling wooden stairs and I arrived at the upper level it was as if I was in a dreamscape and that surely it was not just chance that had brought me in that room, with its wooden beams and ochre whitewashed walls and prints of Van Gogh’s yellow flowers on the walls; I felt so deeply that I was meant to be there, that I had been brought there by some force. I had gone in there in some distress but sitting at the table calmed me, and I felt, as it were, enveloped by the beauty and purpose of Van Gogh’s yellow house.

Some months later I went back to the restaurant. And, it had been renovated, the wooden beams now painted white and Van Gogh’s sunflowers no longer there. I do believe that it was providence that led me there that one evening when I was in need of comfort.

And what a feeling it was to see Van Gogh’s sunflowers in real life (three of the five that have survived), just like Ben, my young, American diplomat artist, in An Act of Defiance: first at the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam, then at the National Gallery in London, and lastly at the Nipponkoa Museum of Art in Tokyo.

I saw my first real paintings in Paris in 1991 at the Museum of Modern Art in the futuristic Pompidou Centre. I can’t describe that first sensation of seeing what a true painting is, what art is in real life is, what it can do, when all you have ever seen of it is in post-cards and posters; the first time my eyes looked at a canvas, saw the actual paint on it, the very real strokes and impressions of brush… it was so much bigger than anything I imagined it would be. To think I knew the works of my favorite artists then- Chagall, Modigliani - and to see that I knew nothing, nothing at all. It was as if I had been given a new set of eyes.

Later, up in Montmartre, even though it was well past its heyday when the impressionists used to gather, still, it was a revelation to watch artists actually painting, their easels and brushes, their palette boards. And to see them at the cafés and bistros causally downing oysters and wine.

A long time ago (1995) I read Jeannette Winterson’s Art Objects: Essays on Ecstasy and Effrontery

and it marked a turning point for me. In my youth I thought art galleries and museums were stodgy places where you walked, got tired, and left in a bad mood. I had never thought that I might actually grow to love them. It was Winterson writing about seeing the real thing, the real painting (as opposed to posters and postcards) that opened my eyes. I love now that she fell in love with painting in Amsterdam because I too truly fell in love with it there, my first look at Van Gogh’s sunflowers. What has remained with me from her essays is that she knew the language for writing, books, but she did not know the language for the visual arts, paintings, and so she set out to educate herself, by looking at paintings, but also through reading, reading, reading. And how I agree with her when she writes, Art opens the heart.

I love art books, from the big, glossy volumes to biographies, essays, letters exchanged by artists, treatises on colour.

One of my favorite places in Geneva is Galerie Bernard Letu, up in the old town. The genial proprietor, Monsieur Letu told me, one afternoon, of the shop’s history - he has been here for forty years. He has a wonderful, hand-picked selection of art books. My biggest fear is that one day I will round the corner of Rue Jean-Calvin and no longer see that round metal sign with its learned, book-reading dog, this cherished place gone, a victim of the sky-rocketing rents in the old town.

Little by little I have begun to understand how painters achieve their effects on the canvas. And still, despite understanding a bit of the how it is done, the wonder remains, perhaps even more intensified, the techniques can be learnt, a person can paint, but for that transformative experience that makes a painting more than what it is, that unknown entity that exalts it into a work of art that makes my heart beat faster, like, I suppose, that unknown factor that exalts a writer’s words from mere storytelling to… a work of art. It is the spirit in the work.

I have just come across an article in The Evening Standard: Painting in Britain: Meet the artists giving a new lease of life to this enduringly popular art form. One the featured artists, Zimbabwean painter, Kudzanai-Violet Hwami says, “I see it as a spiritual experience, of connecting my mind, my body, my arm, and creating something. I’ve not yet come to a rational explanation for why I feel the way I feel when I’m making a painting.”

Every Tuesday and Friday there is a Marche Aux Livres at the place de la Fusterie in Geneva,

and it is here where I have discovered the lavish Sotheby’s and Christie’s art catalogues.

They fascinate me, both the beautiful photographed art works but also their provenance, the wealthy art dealers and families who own them. What must it be like to glance up at a wall, and there your eyes alight on a Van Gogh; do you ever get used to that?

There is a warehouse in Geneva, Geneva Free Port, which has been dubbed the world’s largest, most secretive art museum. In here, masterpieces are kept. The New York Times has reported that there are a thousand Picasso artworks stored here. There are also paintings by Da Vinci, Klimt, Renoir, Warhol, Van Gogh, and many others. These paintings are bought and sold and then stored here as ‘investments’. No member of the public visits this highly secure ‘museum’. What is the value of art, its genius, if it is not seen, what is the value of beauty if it cannot be admired. I think of Van Gogh and his paintings casually hanging in the yellow house.

Every year, one evening in the autumn, there is Art en Vieille-Ville (AVV) in Geneva, when the galleries in the old town open their doors invitingly to the general public and allow them to wander freely for as long as they like while sipping glasses of wine. It is a wonderful feeling to walk those ancient cobbled streets, to finally enter galleries whose heavy doors are solidly shut the rest of the year, daring you to open them, go into the hallowed spaces where art hangs that is way way way too expensive for you. On this evening there is no judgement being cast upon you. The galleries on this day are art museums but free, and they give you wine for gracing them with your presence. It was one of those evenings that, walking down from the old town, at its outer fringes, I came upon a gallery, Salomon Lilian Gallery, Dutch Old Masters, on its doors.

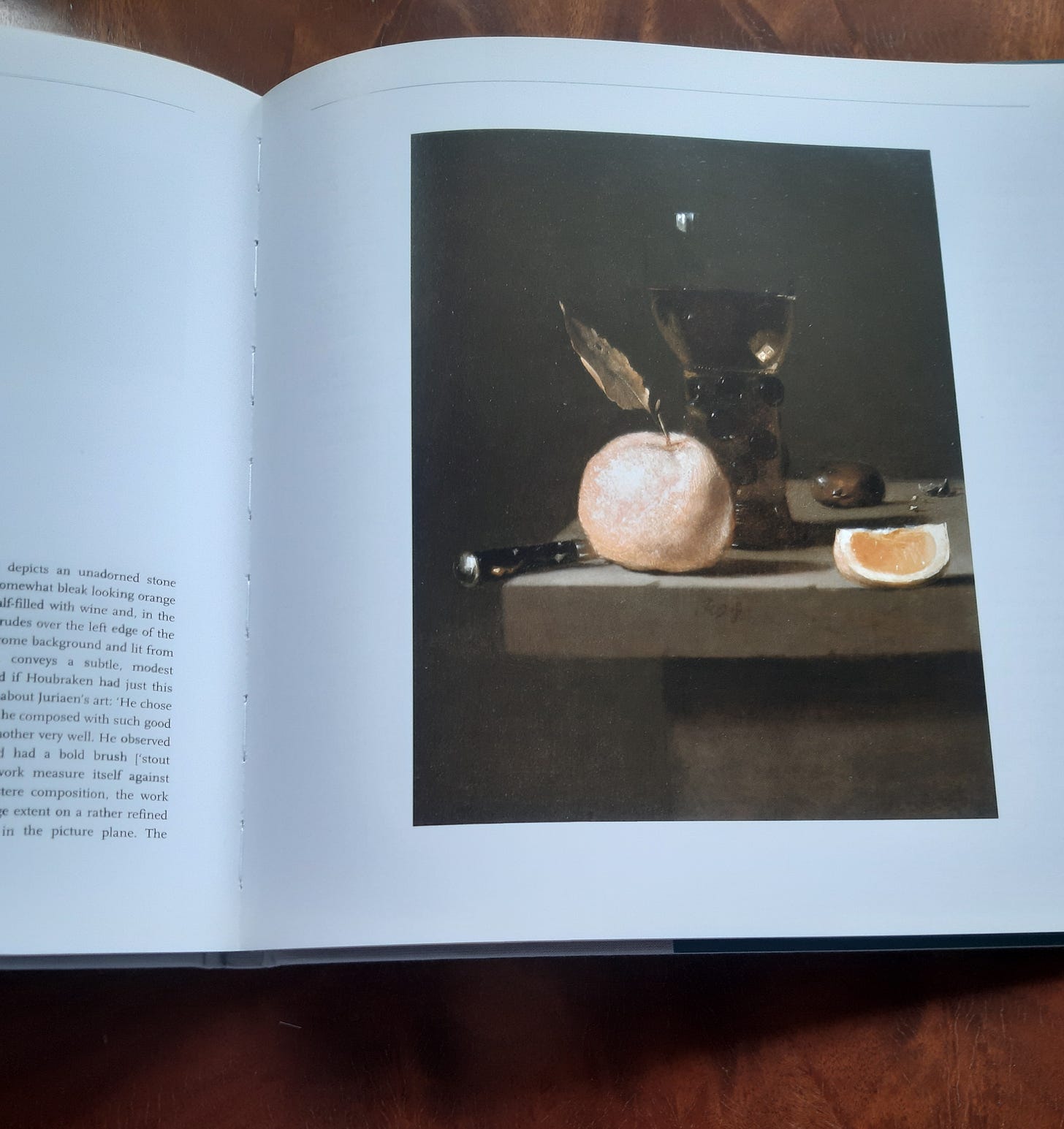

I went inside and, there on the walls, my eyes fell on a Nature Morte, and so began my love affair.

No matter how terrible I may feel, looking at these Dutch still lives, always lifts me; a kind of ecstasy overcomes me, a burbling I feel in my mouth.

Natures Mortes, literally translated, Dead Nature, but transformed by the artist, to a living thing, art, which moves me, sometimes to tears. The lacquered fruit, the grapes so glossy I feel I could pluck them from the table they lie on and put them to my mouth, the peaches fuzzy - I reflexively rub my fingers as if they were in my hand…everything that lies on the table, alive. But it is not only the objects in the paintings, how masterfully they have been brought to life that is compelling, it is their arrangement on the table. I know that the artist has arranged them just so, that the arrangement does not come by accident, that his hands have placed this here, and here and here, that he has moved and rearranged, moved, until he is satisfied and then he begins… but still, looking at the painting, this knowledge all falls way, and I am left with the objects, the arrangement, as memory. An abandoned meal - the glass of half drunk wine, the slab of cheese, the piece of bread, the segment of an orange… the stories that lie there.

The Natures Mortes can have scenes of violence, the aftermath of a dear hunt, a rabbit hunt, deer and rabbit flayed open in a medieval kitchen. I came upon scenes like these in the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto.

I stayed for the longest time looking at Jan Weenix, Nature Morte au Levre, 1703, Still Life with Dead Hare, the rabbit strung by one foot amongst the decaying fruit, the image so real that I might have been on that hunt and strung that rabbit up myself, sniffed at the fruit, perhaps plucked a couple of still good grapes and popped them in my mouth. I became one of those people I scoffed at in museums; I took pictures. Lots of them. Hurriedly, not because it was not allowed, but because I was being so gauche. But, I wanted to remember those moments when I looked at the paintings, how I saw them then, what that moment felt like to me.

In Montreal, the newly constructed Michal and Renata Hornstein Pavilion for Peace at the Museum of Fine Arts, named in honour of its generous benefactors, a couple who had survived the Holocaust and made Montreal their home, was awash in Old Masters; the couple had gifted one-hundred Old Master paintings. I was in heaven, I could not get enough. There was the Cabinet of Curiosities, a dimly-lit passage of rooms which I wandered up and down, struck by the Natures Mortes on the walls and the objects on display in the cabinets. I had never seen such a thing before.

And even though I read how these objects of curiosities had been acquired by the Dutch in their expeditions - that they were often the result of pillage, as the exhibit itself acknowledged - while these painting offer moments of beauty and reflection some of them also contain reminders of the human cost of this newfound wealth. Many items of luxury, such as tobacco, sugar and gold, came to the Netherlands from the colonies through the labour of people enslaved by the Dutch - seeing them in the paintings, how they radiated an energy there, cast a spell over me.

I was fascinated by the ‘memento mori’, a term I learnt from a caption of a still life: Glass Tazza with Peaches, Jasmine Flowers, and Apples by Fede Galizia, the only woman artist in this particular exhibit.

Some scholars have read Galizia’s painting as a memento mori (reminder of death) interpreting the browning half-apple as a representation of the passage of time and decay.

I understood now the skulls in many of the paintings I had seen, placed there on desks among pens and notebooks.

From the Vintage Thrift Shop in New York I have salvaged some still lives.

Their artistic worth might be minimal but I treasure them for how they make me feel, and how they suggest that art can be made in the everyday objects around us, how the arrangement of fruit on a bowl, a miniature jug, can create something of beauty.

I love the idea of finding art in everyday things.

In Soetsu Yanagi’s The Beauty of Everyday Things… in order for beauty to prosper in this world, and in order for us to gain a deeper appreciation of beauty, it is necessary for the utilitarian to also be beautiful. Which brings me to Giorgio Morandi, who I discovered while browsing in New York’s Rizzoli bookshop. Morandi hails from Bologna and he never travelled, never married, lived (1890-1964) from 1909 to his death in the same house with his mother and sisters, where he had his studio, and he painted the same set of everyday bottles over and over, mostly in shades of brown. If he were a woman his art would be called ‘domestic’ and I wonder if its enduring nature would be questioned; would I look at his work and experience it differently. I recently saw my first Morandi painting at ArtGenève, a very small canvas of two indistinct shapes, opposite a De Chirico (whom I also love). There were also ceramics by Morandi in dull shades of pink, small bouquets of flowers. I had been wandering listlessly about the expo, put off by the garish nature of the exhibits, the well-heeled sipping champagne, the cordoned-off areas for wheeling and dealing, when I stumbled on this exhibit and knew at once that here, this, was the real thing. There is, as the book tells me, something metaphysical about Morandi’s paintings, how he captures the light, the quality he imbues each brushstroke so that the bottles become more than the physical object itself, and I feel it here as I stand in this space, suddenly transported out of place, time.

I love flea market and thrift shops for the delight of the unearthed beautiful object of a bygone era. A liqueur decanter, a vase, china, a chain-link purse… all of them giving me pleasure when my eyes fall on them.

At the Bulawayo Art Gallery

there is a beautiful space: a courtyard around which are rooms converted into artists’ studios. As I sit down on the verandah of the café I catch glimpses of artists at work in their studios, artists visiting each other, artists walking along the corridors and here is one now, crossing the courtyard, a canvas in his hands. I work up the courage to go into a studio, and what a wonderful thing it is to talk and watch the artist at work, explaining his work with mixed media, strips of Bulawayo’s The Chronicle newspaper on the table. I leave with two of his works. In the gallery itself, a sculptures holds my attention and I circle back to it, over and over.

Every time when we go to the medieval village in the Apennine Mountains where Fabio, growing up, spent his summers (escaping the heat in Rome) and winters (to ski) there is a spot in the village where, standing, at a certain time when the sun is just so, I am transported into a De Chirico painting; I can imagine the great man here with his easel, working on his canvas, lengthening shadows, distorting perspectives, adding incongruous, unsettling elements like a giant plastic glove pinned on that wall there, a Roman bust, or some off-kilter figure… and my heart opens, for this is what art gives me, the world made new again.

Images from Giorgio de Chirico's House

Coda: Extract from The Rhodesians (unpublished)

Harare, 1981

The paintings were done. All six of them. One for each window. The unveiling ceremony was this evening in front of several of the twenty white MPs and the Mayor. She painted them all in the stable. No-one has seem them. The canvases would be placed in the windows after the unveiling. As she tied the knot on her blouse her hands shook. She stopped, breathed and tried again. She was nervous. She had not been nervous with the Chinese Propaganda wall because that was a safe bet. This, this was anything but. This was art and she was not sure Rho- Zimbabwe was ready for it. But, after everything that had gone on, maybe the country was ready for anything.

It had been quite the joyride, these past few months. British royalty jetting in to govern them, a lord, no less, and the terrorists who now you had to call ‘guerrillas’ or ‘liberation fighters’ supposedly handing in all of their weapons and going into camps. Then Prince Charles jetting in, what a frenzy that had been, all the unmarried girls thinking that they had a shot at being his wife, if only they could score an invitation to State House. Marge Dickens had spread the word that Miss Jacaranda and Miss Rhodesia had almost come to blows at the club. And then all the frenzy with the elections, getting used to seeing the former terrorist on TV in suits, campaigning, And the shock of the results when the ‘lesser of two evils’ was resoundingly beaten. Who would have thought that they would be ruled by a baby-eating communist, not the Ndebele who people in the know were convinced would win, although, looking back, they could have worked it out, it was all tribal politics with the Africans. Lots of families had packed up and left after the results. They would have been willing to put up with Nkomo but not Mugabe, who had been taught everything he knew by the Russians. He had that look of a killer, while Nkomo had a grandfatherly, good-natured air about him which was not to say him and his army hadn’t done as much damage as Mugabe’s. But he, Mugabe, had surprised them, what with his talk about reconciliation, and he had even kept General Walls as head of the army could you believe it, and army made up of well-trained Rhodesian soldiers and terrorists! Nobody was coming to grab people’s properties. No gangs were going into homes, dishing out beatings, looting, raping the womenfolk and slitting the throats of white babies. Everything was as it was before, even better. Sanctions had been lifted! The country wasn’t a pariah state anymore. All kinds of people were coming in - tourists, word was the Victoria Falls was so packed you couldn’t even see the spray, and those aid worker people who were driving around Sal- Harare with their shiny land rovers with white number plates who were so convinced that the Africans needed ‘aiding’. Hotels were fully booked with some strange types who thought that there was money to be made - so many minerals! Business was booming. The Dickson’s Employment Agency was a case in point. There was so much ‘aid’ money pouring in, construction projects being planned, that their officers were being flooded with new ‘corporate’ clients who were looking for mangers and fore-persons.

The Dickson sisters were now all go, go, go, a far cry from the 17th of April when they had showed up at her doorstep, and had only left on the 19th. They had watched the Independence Day handover together; word had it that the men had gathered at club again having a real booze up and blaring Clem Tholets hits as their last stand. The sister were convinced that come midnight, once the Union Jack was taken down, handed over to Prince Charles to take back home to his mother and the communist baby-eating terrorist took his oath to be Prime Minister (!) and on the Bible no less, all hell would break loose; the natives would run amok, their maids and gardeners and cooks would have all their previously checked savage impulses released. Their would be a frenzy of rioting and killing and thieving and raping and white babies would have their throats slits as they slept. They could not stay home alone, waiting for the inevitable. It didn’t seem to occur to them that they were in this house, alone with her because Richard was at the grounds, in the thick of it, taking his pictures. The day had worn on, the ceremony had gone without a hitch, the sisters had started crying as the Union Jack was slowly hoisted down.

‘It should be the Rhodesian flag,’ said Joan.

‘Those poms never recognised Rhodesia,’ said Marge.

‘Bloody traitors, the lot of them.’

‘The Rhodesian flag is still flying, that’s all that means. They can put their new flag up, but the Rhodesian flag is still flying.’

But Rhodesia was now Zimbabwe. The sisters, who had consumed quite a bit of gin and tonics, jumped at any noise. The hordes were coming. They were sure of it. It was only a matter of time. Once they closed their eyes… but by the time Bob Marley took to the stage they had retired. It was Richard who told her about the near riot because the stadium was full to capacity and thousands of people outside were trying to get in, pushing through the barriers. Poor Marley had to sing through the tear gas.

‘Ready?’

Funny that Richard had been around for both of her unveilings.

‘Wow,’ he said when she turned round, picking up the black clutch bag. He was looking at her as if he wasn’t quite sure who he was seeing. She was wearing black palazzo paints that she actually had sent over from South Africa and a silky cream blouse with a pussy bow that she had finally managed to tie. Her hair was actually styled into big curls that grazed her neck and she was wearing a pair of high heels which she had been stealthily practising walking on for weeks. Her face was made up - the works - foundation, rouge, blush, eyeshadow, mascara, lipstick - she had considered false eyelashes but thought that really was a bit much. Her nails were done. This was body armour. She was armed. Or perhaps she was hoping to disarm them all with her costume. Richard was certainly disarmed.

As befitting her new persona he held the car door open for her. And her entrance in the room of the ground floor of Barbours, which had ben cleared of the perfume counters and stationary and replaced with high round tables with tall vases of flowers (flame lilies) and bottles of wine and champagne (no sanctions!), brought the room to a stand still. It was a movie star entrance, and suddenly she felt utterly ridiculous. She wanted to kick off these heels which were straining her calves. They were actually star-struck. It’s me, Mathilda, she wanted to scream to them. Just me. Not a movie star. It was as if they couldn’t see past the costume, the artifice. They were dazzled. And that had been her intent, hadn't it. An official took her in hand, led her to the podium that had been erected. Her paintings lined one side of the room set up on easels covered in a white shroud, linked together by a red velvet ribbon. It was unsettling to see them out of the stables.

She felt suddenly hot. She needed a glass of water but she was afraid to pick up the glass at the table. She would almost certainly drop it.

‘You all must remember the success of the painting she did for the Richardson’s Advertising company. If you haven’t seen it you must go down there and take a look for yourself. It’s a magnificent piece of artwork. We are delighted that she agreed….’

On and on it went. The heat kept rising. She felt the sweat start dribbling down her armpit. The blouse would be stained.

‘….Mathilda, if you may say a few words.’

What? She hadn’t been warned about this. She felt like bolting out of there but they were clapping, urging her own. She got up, managed to walk the few steps to the podium without falling over.

‘Yes, thank you (she had forgotten the name of the guy who had just spoken and was she supposed to say honourable so and so?)…’

Someone coughed.

‘Thank you. I’ve titled the six paintings Renaissance (that had just come from the top of her head) and I guess they are inspired by Matisse’s work. Thank you.’

She stood at the podium. Nothing happened for a couple of seconds, perhaps they were expecting her to go on, and then there there was a solitary clap which came from the podium (perhaps the man who had spoken before?), a flash of the camera (Richard?) and the audience clapped. She went back to her seat, sure that her sweat stains had spread so much that they were visible to all and sundry.

‘….well, ladies and gentlemen we have the Honourable Member of Parliament, who will do us the honours of unveiling these great works of art.’

She had regained her composure. Come what may, she was proud of these paintings. They were not frauds. She didn’t know if they would make it to the windows at all. So be it. She had given her heart and soul to them. But, in a sense, she already considered them ‘not hers’ which in the business sense they had never been, but this was more than that. They would be in the Barbours’ windows (perhaps), tastefully hidden (perhaps) with baubles, gift items…

The moment had arrived. The MP had received a rowdy round of applause and cheers. He wielded the scissors, cut the velvet ribbon and the hired help slowly, carefully lifted the white shroud to reveal the paintings in all their glory.

…

Sixteen paintings, must be sold, despite the dealer’s protests, en masse. In each painting a woman (naked of course, coarse, dimpled flesh with bruises on the torso like bite marks) floating, hands and legs splayed out, hair in plaits standing out from the head like soldiers.

On each face, a twisting of the lips which most likely is a grimace but could be an unaccustomed smile, a nervous gesture. The head is flung black, neck stretched taut, each woman straining to look at the figure in front of them, trying to get a glimpse of it. Eyes large, rolled back. Tongue stuck out, tip curling inwards, hints of teeth. When viewed as separate entities the paintings are thought strange, not unnerving. Viewed as a whole, the sixteen paintings in a ring (the arrangement in the gallery is such that only these pictures can be displayed as they must occupy all the walls of the gallery precisely as how the artist states), confuse, disturb. One feels that they are witnessing an orgy of women. For some inane reason the childhood rhyme, ringa ringa roses, rises in the head and this appals the viewer, for what does it say about them. What kind of perversion makes them think of children, linked hands, dancing feet, frolicking around a trees when they look at these women? There is something childish though with how each woman ogles the other, something childish about wanting to see so desperately, about being in that position, flat on the ground, arms and legs spread out, one can see children lying on grass like that, one after the other, telling tales, secrets, wrinkling up their noses, counting clouds. But these are not children and the air that they float in is a black space. The viewer looks closer at the painting, wrinkles up their noses at the stubby fingers, the cracked heels, the sagging flesh off the forearm, the double chins. The assault of age and ugliness proves too much. One looks away. But they form a circle around him, her. He, She is imprisoned by each woman, taunting him. I am old. I am fat. I am ugly. You can’t escape these things. They are part of the world too.