I recently went on a four day trip with Fabio to see the Matterhorn, the peak in the meadows, our first trip together as official empty nesters. In the canton of Valais where the great mountain is situated, straddling the border between Switzerland and Italy, I became entranced by the plethora of life-size crucifixes, with their hyper-realistic renditions of Jesus nailed painfully on them.

We first stumbled upon one in Visp, a town that our guide book dismissed as not worth staying over in, but in which we did and found rather charming. I had the most delicious spaghetti alle vongole at a restaurant in the square and, after polishing off a bottle of red wine, we decided to walk up to the old town to digest. The cobbled stones led us up the hill to a square with a seventieth-century baroque church, St Martin’s Cathedral. I walked up the ancient stairs and then stopped in my tracks, as I looked out to the porch, where a cross was on the wall, framed by an archway, a figure on it.

Walking up to it, it was as if I was in the biblical story, a believer come to see the Son of God. And then I was there standing, looking up at it. The feeling it gave me to look at that cross, which might have been hammered down on another hill, Golgotha, so many century ago. And on the cross was a man. The figure was so lifelike, the nails driven through the flesh made me shudder, arms stretched, ribs taut against flesh, flayed heart bleeding, and the crown of thorns tearing into flesh.

I stood there in silence in the quiet night and it was as if I was being called to believe again.

There was yet another such cross in the cathedral in Zermatt, and once again, even though this time we saw it during daylight, there was the same strength of feeling it invoked me, as if I was that impressionable child again, looking up at the crucifixes on the school walls, or the pictures along the corridors of the beatific Christ with the heart split open. The wonder and terror I felt back then, magnified now, because I was an adult and should know better.

There was a simple cross - two logs with a small Christ, on the summit of the Gornergrat, which we had come to by train, planted in the dirt, backdrop of sky, snow-capped mountains, glaciers, hills, and meadow. It was a pastural scene - simple and majestic, a bench on the side of it where hikers and bikers rested, sipping water.

The last crucifix we saw by chance when we decided to make a stop on our descent back to Zermatt because Fabio was fascinated by the mist that had suddenly enveloped the mountain and he wanted to see it up close. We got out at Riffelberg and sat at the terrace of a little lodge and while drinking tea watched the mist rolling in and out of the mountain, the valley, a hide-and-seek game, the matterhorn appearing and disappearing, the trails with their hikers vanishing, how that would have panicked me if I was one of those hikers we were watching appear and disappear - we were so close we could see the sheets of water that made the mist. On our way back up to the tiny station I saw the cross. It made me think at once of pre-Colombian and Native American statues and imagery. It stood there on the hill, as if the gods of the Amazonas were laying claim to this god too.

The crosses have left their imprint. Perhaps if I believe again, the purpose will be there, always, even then the writing is not, and I am sunk into existential despair.

When I was ten I was confirmed into the Catholic Church.

It was memorable day for me, not so much for the ceremony (and my receiving of the ‘body of christ’ wafer for the first time, the wonder (and goriness) of the priest placing it on my tongue and it melting there, not knowing whether I should swallow it whole, suck it or chew it (what should one do with the ‘body of christ’?)), but for the feast afterwards, the rows and rows of trestle tables in the church hall, piled high with all kinds of cakes and sandwiches, and the little gifts each one received, a rosary and a plastic tableau of Mary, Joseph and baby Jesus.

For a while, I was a good catholic. I attended Mass at the Cathedral adjacent to our school, and during lunch times I was part of the liturgy group that recited the rosary by the grotto that was tucked away in a corner at the edge of the sports grounds.

But, when we moved house, I joined the youth group of the neighborhood Methodist Church and its, what I thought then, rock and roll liveliness kept me as a member for most of my teenage years, until suddenly my faith wasn’t so sure (and anxiety inducing - was thinking of thinking a bad thought a sin?), most likely because of my ‘revolutionary’ protest years at university and my wide-ranging reading there from Malcom X to Simone De Beauvoir.

I was about to write that the last time I was in church for a church service, that is attend for worship (not including weddings), was when I was sixteen but then I remember that about two years after moving to New York I stopped as usual in front of the church on Madison Avenue between 30th and 31st to read the marquee board: it always gave me pause for thought because of how varied it could be: inspirational quotes: Too often we enjoy the comfort of opinion without the discomfort of thought, JFK; The way to right wrongs is to shine the light of truth on them, Ida B. Wells; We must learn to live together as brothers, or perish as fools, Martin Luther King; or keen observations about life in America, Rather than a wall, America needs to build a giant mirror to reflect on what we’ve become. On this day the doors were open, and I was so tired after a walk that had taken me all the way to the West Village and back again; I walked up the stairs and stepped into the church mid-sermon. It was sparsely attended, perhaps ten people in all. I sat on one of the benches and, once my breath quietened, I was confused, then amazed, then amused, to hear the priest talking in earnest depth about the ins and outs of some television soap - I think it must have been one of those daytime shows, because the plot, as I leaned closer, once I figured that he was not talking about real people, real events, seemed somewhat outlandish; I waited for him to reach his point, the teaching of the sermon and of course it had to do with loving thy neighbor, nor matter what back-stabbing shenanigans they get up to, I suppose. I left before the sermon ended, guiltily, because it seemed to an indictment of the good man’s ability to hold an audience.

When I am asked what I believe in now, I say that I believe in some form of spirituality. Perhaps it is because of my upbringing that I cannot let go of the sense of, the need for, some greater other, some thing; the universe may be explained by the Big Bang, and our existence through the process of evolution, science, but something in me says, yes that is true but what is the more.

In Tokyo, I was drawn to the temples - I was overcome by a profound sense of calm at the Meji shrine, listening for hours at the wind whistling through the trees in the forest. Perhaps it is my growing love for mountains, for what I felt when I was in Zermatt and how I have grown to love Nonnas’s cabin in the Appennines, Monte Cagno, almost at our doorstep, that I find myself looking more and more to Shinto, with its veneration of nature. It seems to me to be more generous, more forgiving, more encompassing of multitudes.

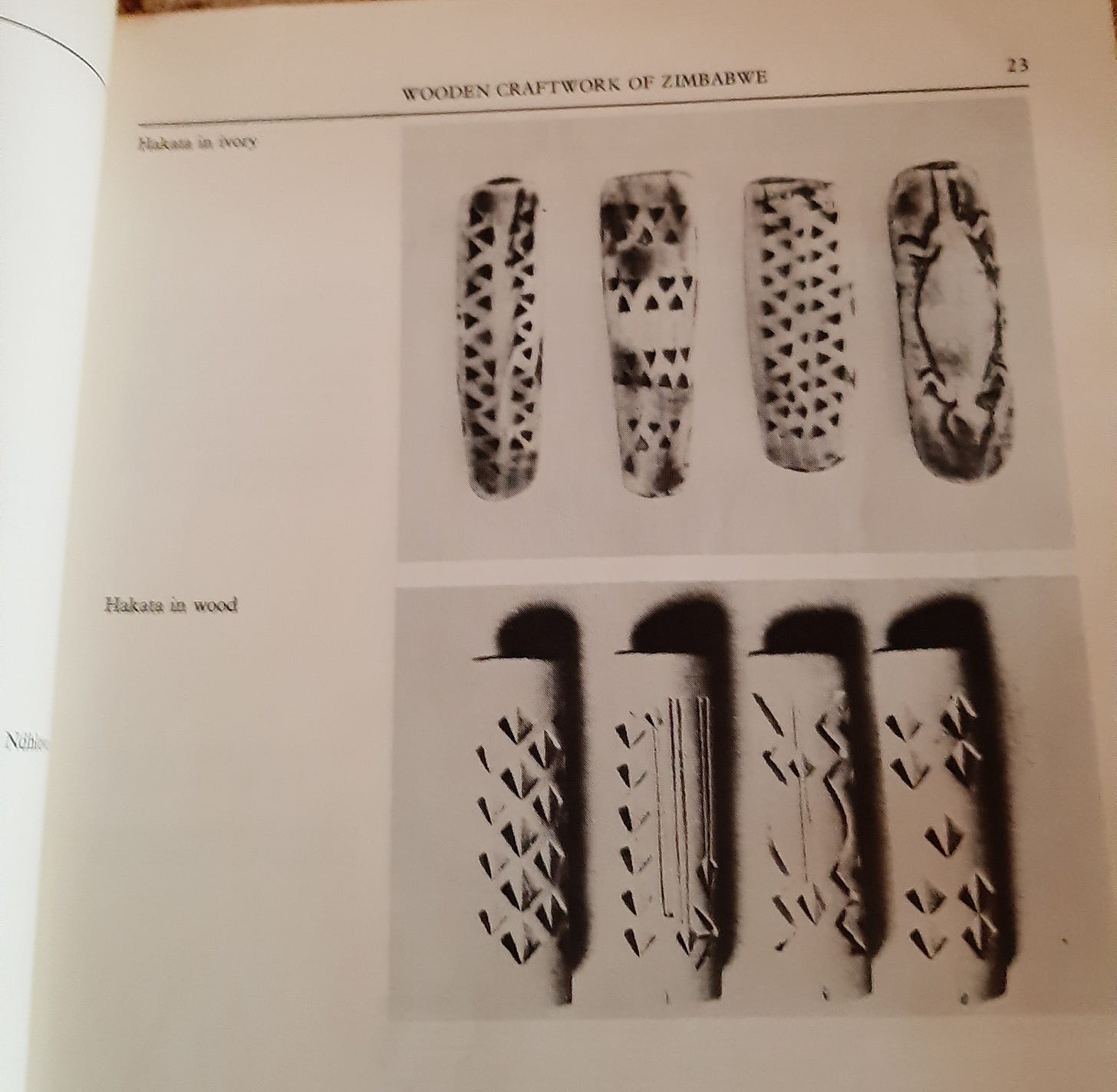

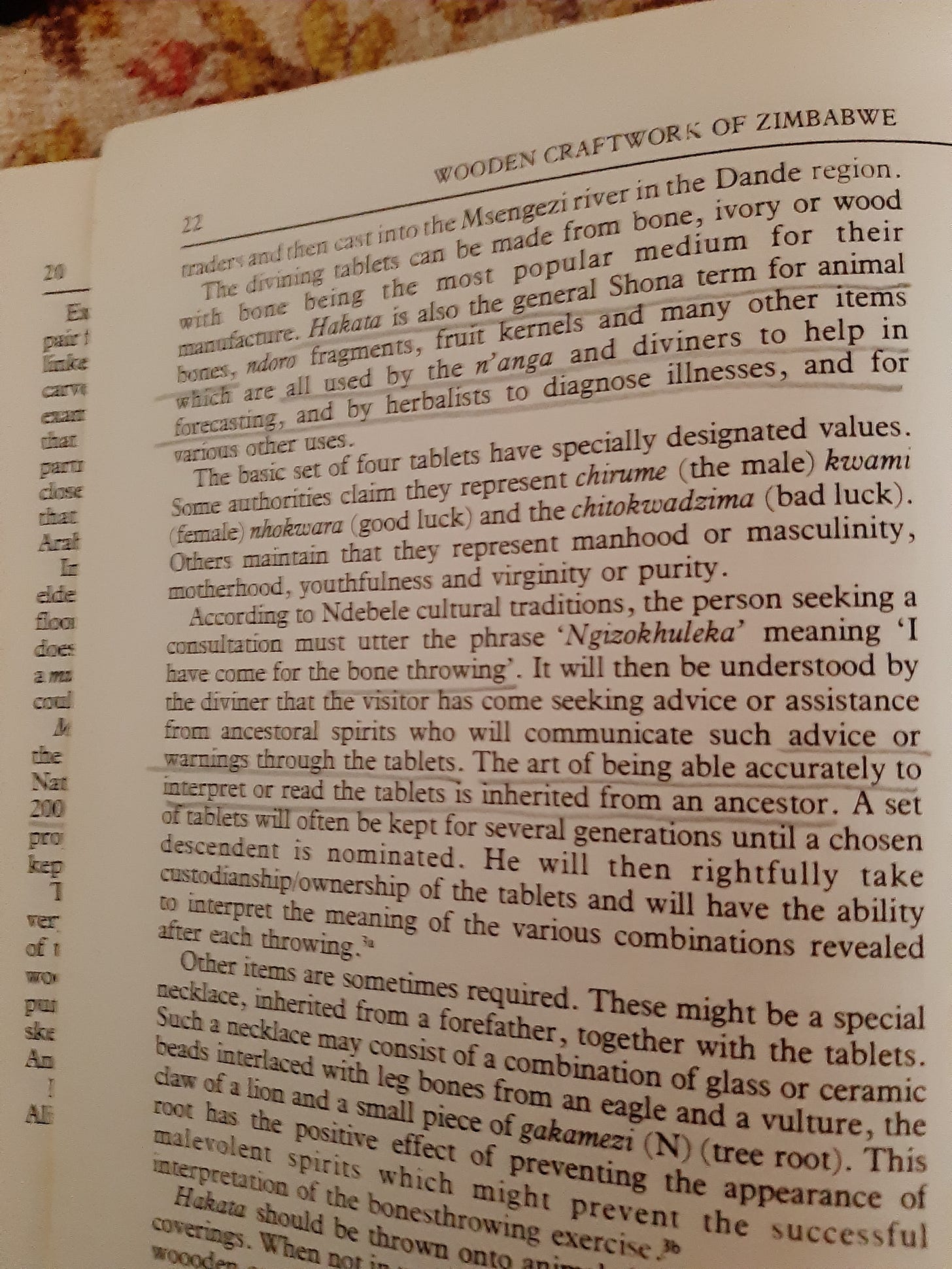

In Kuala Lumpur, R and I stumbled upon a temple. It was a shock to go from the humid chaos of Petaling street in Chinatown to the cool shelter, the smell of incense (which normally I do not like) here, at the shrine, like a balm. A woman came to us, charming and bubbly, asked if we would like a tour. It was the Sin Sze Si Ya Temple, the oldest Taoist temple in Kuala Lumpur. A soon as R heard ‘Tao’’ he perked up. He had recently done a project about belief systems at school, and he had chosen Taoism as his, and here we were, unexpectedly, in an actual Tao temple. There were elderly men and women gathered in groups doing various activities, reading papers, playing a game of mah jong… because it was also a cultural centre for the Chinese community. She took us to each station, explained the meaning and philosophy of what we saw. There was a young man standing earnestly before a statue. That was the God of Education. The young man most likely had a big exam coming up and he was praying for good luck. There were other deities: of beauty, young girls with acne prayed here, together with wives of cheating husbands, and fertility. Crawling under that table over there helped lessen mortal burdens and, circling the temple’s main altar three times brought good fortune. There was fortune telling, too. She picked up a bamboo cylinder filled with sticks - they were kao chim (fortune-telling sticks); you had to shake the cylinder until a stick fell out. Each stick had one unique numerical, which corresponded to an oracle written on pieces of paper which would speak of the devotee’s future or prophecy. The Kao chim sticks are very much like the hakata that n’angas, traditional healers, in Zimbabwe throw to divine fortunes.

When we were outside the temple I asked her, thinking she was an official guide, how much we had to pay, and she smiled and shook her head, thanked us for letting her share the love and peace and optimism of Taoism with us, and bade us a cheerful good-bye. I loved the temples’s curious and uplifting mix of the divine, its deities and alters, and the wordly, so that one moment you were praying to the gods, and the next watching someone flicking through the day’s paper.

I do not believe that I can be a real Shintoist or Taoist because I do not come from that culture; I cannot claim them for myself. Even if I should study, I cannot truly understand what it means, the centuries and centuries of thought and teaching and just being born in it, being of it, the land and people it has arisen from. I’m not a coloniser. I cannot appropriate this spirituality, this way of being. And yet, the call is there: African animism shares much of the same beliefs - the worship of the ancestors, spirits and nature - if I could be wholly of that - but the missionaries came and brought their stolid teachings, and I am of them.

If I am to return to Christianity I think it would be to the austere Swiss Calvinist branch of it. In Cathedral St Pierre, up in the old town of Geneva, I feel a quietness descend upon me in the sparse, austere church, which is not there when I enter the lavish Roman Catholic cathedrals, full of what the kids call ‘drip’.

But, I think, if I am truly honest, what I am looking for is really not spiritual enlightenment but quiet, something to still my rapid heartbeat, the palpitations that seem to come out of nowhere or from the slightest upset or the expectation, anticipation of one.

Browsing at the Payot bookshop in Geneva I come across a book (in translation) by Kyunosuke Koike, a former Buddhist monk - The Practice of Not Thinking - A Guide to Mindful Living. Cringing at its self-help title, I made to put it back down but that title spoke to me - The Practice of Not Thinking - for I am always thinking - not daydreaming - actively thinking. Alone, out walking, I actively make up stories where I am the lead protagonist. I have several stories and I enact them as I walk. Is this normal? G asked me once how I could walk without any headphones, without listening to music. How is that even possible? Well, I could have answered him, once upon a time, in the land before mobile phones, people did that all the time, you know, walked without something in their ears.

Sometimes, I fear that I may get so far deep in my stories, my imaginary world, that I will lose my perspective on reality. This active thinking, I know, as I read the title again, is a reflex away from being by myself, fearful of what will happen if I hit ‘pause’, if there is no thinking, fearful of that emptiness that I must breathe into, fearful that I will be left with dispair, I suppose.

I try to pinpoint exactly when I started doing this - making up these stories, living in them - it is not as a schoolgirl or young woman in university, not as a young woman in Colombia, Barbados, Zimbabwe, not as a young mother in Geneva, not as a published writer in Geneva, not initially in new York… when then?

The year before the pandemic.

I have always been prone to anxiety, but menopause has heightened, exacerbated, it. I wonder now if my stories are a desperate, misguided attempt to escape this anxiety, waylay it. I want quiet, the ability to be still. To acquire zen.

I turn to the back cover. When we focus on our senses and learn to re-train our brains and our bodies we start to eliminate the distracting noise of our minds and the negative thoughts that create anxiety… only by thinking less can we appreciate more….

I buy the book.

After our return from Zermatt I slept throughout the next day. How tired I was! All that fresh air at peaks of above 3000m had wiped me out. And poor Fabio with his peeling nose.

Up resting in a lodge I had watched much older people than me hiking on the mountain trails.

And I thought of Rousseau, citoyen de Gèneve, how he largely walked from Lyon to Chambery, just over one hundred kilometeres, and his love for nature. When I got back home I picked up his biography that had engrossed me for days, Jean Jacques Rousseau, Restless Genius by Leo Damrosch.

Describing the Alpine foothills, Rousseau wrote

….a blue chasm, a fracture in the vapor,

A deep and gloomy breathing-place through which

Mounted the roar of waters, torrents, streams

Innumerable, roaring with one voice.

And, as I now read Van Gogh's biography, I think of the ‘it’ he sought all his life, the essence which makes art, which is found in nature. That which can calm, give solace.

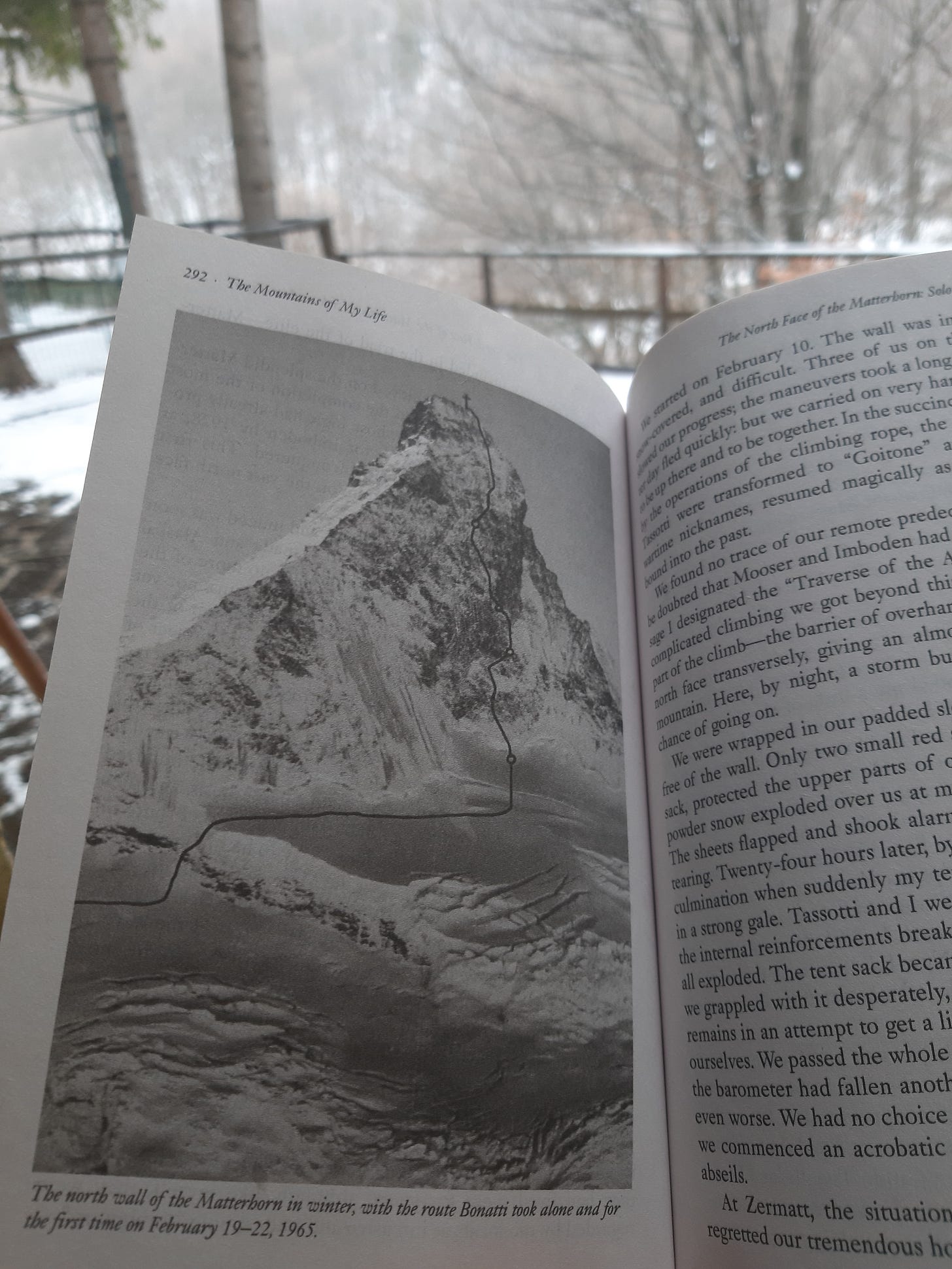

Days later, recovered from Zermatt, I found this title under ‘Leisure’ in Payot: Walter Bonatti, The Mountains of My Life. I don’t quite understand how leisurely it must be scaling mountains like Everest, the Matterhorn, that I have now seen up close, thanks to the Gornergrat Bahn that went up to 3000m, seen its glaciers and jagged rocks, how much will and effort and courage to even dare.

Inside the front cover:

Water Bonatti was born in Bergamo on June 22, 193. As a young man he dedicated himself to extreme alpinism, and from the age of nineteen to thirty-five he climbed a succession of increasingly difficult routes…. In 1965 he achieved an unheard-of-feat - the solo direct ascent of the Matterhorn in midwinter - after which he abandoned extreme mountaineering.

I buy the book.

I take it to the cabin in the Appennino mountains.

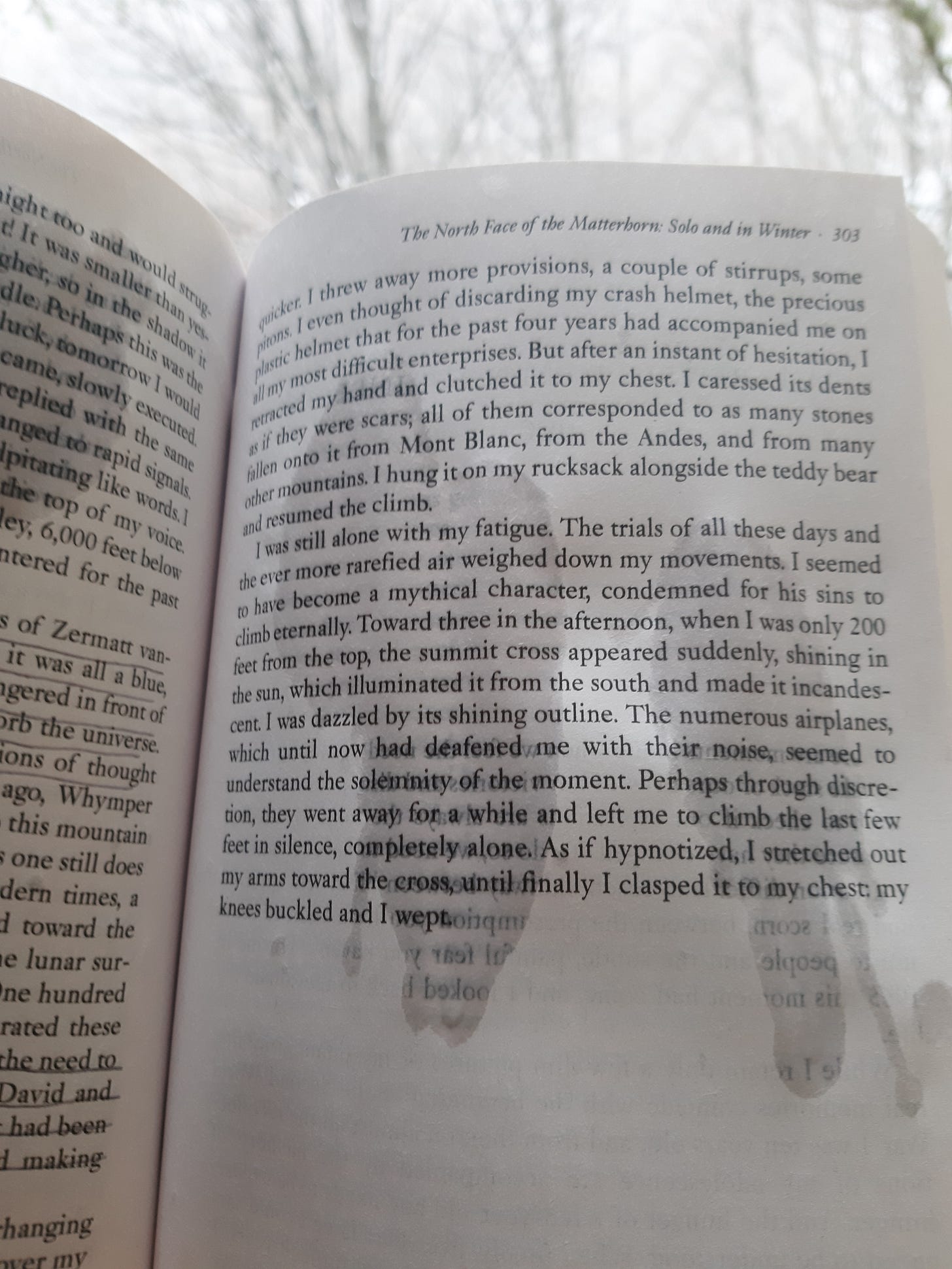

Sitting on the verandah, facing the mountain, I head straight to Chapter 18: The North Face of the Matterhorn: Solo and in Winter, (1965)

I read the last two lines over and over, Bonatti overcome, stretching his arms towards the cross, clasping it to his chest, his knees buckling, weeping.

This particular cross on the Matterhorn is a metal one and it commemorates the people who have died trying to reach its summit.

I did (unwittingly) hike up a mountain, once, with Fabio. It was mere months after our first meeting. We had driven to Chimanimani in the Landrover, slept at the Chimanimani Hotel. In the morning we had asked for packed sandwiches which we put in my army-style backpack and then we casually set out. I had no idea that we were actually climbing a mountain. I thought we were going for a walk. But climb we did. I was wearing shorts and plimsoles. In The Boy and Next Door, Ian takes the unsuspecting Lindiwe on a walk:

“Tired?”

“A bit.”

“Worth it though, huh?”

“Yes.”

We’re standing at the foot of the falls.

The light catches the water as it splashes and spills over the stones, and yellow butterflies slip and float out of the streams of falling water…

…I think of how many times he took my hand, helped me over a log, a rock, a ledge, cleared the path for me, as if it was the most natural thing in the world. How we both stood still when we came to a little meadow with a stream running through, and just as he had done with the birds so many years ago, he named the flowers and grasses for me….

Our hike was very much like Lindiwe and Ian’s, but our stories did diverge at one point. Reaching the National Parks hut (1630 metres) and mightily exhausted, Fabio and I dropped the rucksacks on the ground and we slumped down on the chairs that were out in front on the verandah. There is a picture of me sitting there, looking out into the wide valley, out across to the other side, Mozambique. I didn’t think then, that the valley was lined in landmines from the ongoing civil war in Mozambique.

At some point I turned, just in time to see two crows attacking the rucksack and making off with our dinner. Fabio and I were famished and we hunted hungrily in the mountain hut for food. We ate the dire crumbs that the previous hikers had left, and we even searched the dustbin. There was nothing for it but an early night. We settled down on the benches - we had not even packed sleeping bags. But as soon as it was dark, the hut filled with screeching sounds. Bats. And lots of them, flying from one end of the room to another. I was petrified. I doubt I slept. The next morning - the long, hungry hike down.

But, what I treasure most, was the meadow that suddenly appeared as my trembling legs climbed over a rock, there it was, grass and flowers stretching into the distance, and Fabio and I took off our backpacks from our sore shoulders and we lay on it, respite. This was ‘it’, I know now.